Number of highest-earning Canadians paying no income tax is growing

By Monday, most Canadians will get their annual taste of tax theory at work: the more you earn, the more tax you pay.

But not quite everyone.

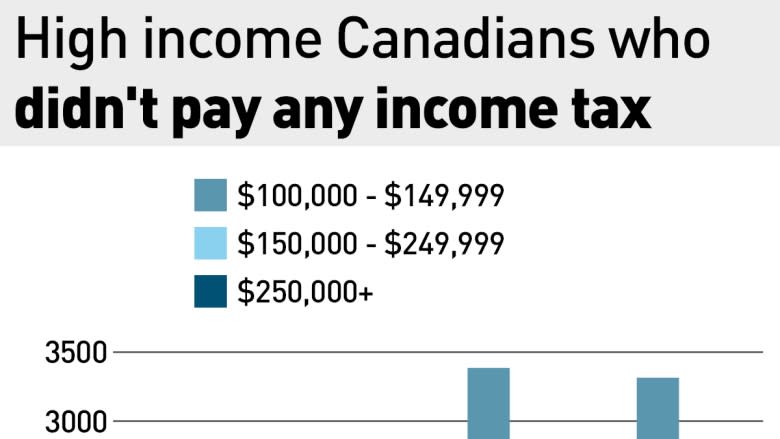

A CBC News analysis of Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) data shows that, between 2011 and 2014, a growing number of Canadians earning a six-figure income or more didn't pay a cent in income tax.

The analysis compiled all individual income tax and benefit returns filed with the CRA and focused on the top three income brackets: $100,000 to $149,999, $150,000 to $249,999 and $250,000 and over.

During those four fiscal years, the number of Canadians who legally avoided paying income tax rose about 50 per cent from 4,050 to 6,110. The number of filers who made more than $250,000 a year and completely avoided taxes doubled.

The CRA says, "It is possible for individuals classified in the upper income ranges to reduce their tax liability to zero by using deductions such as business or farm losses of previous years and allowable business investment losses, or significant contributions to RRSPs.

"Tax filers can also use non-refundable tax credits such as charitable donations, or dividend and foreign tax credits."

Since April 30, the usual tax deadline, is a Sunday this year, the CRA says, it considers a tax return to be filed on time "if we receive it on or it is postmarked on or before May 1, 2017."

450 returns from outside Canada

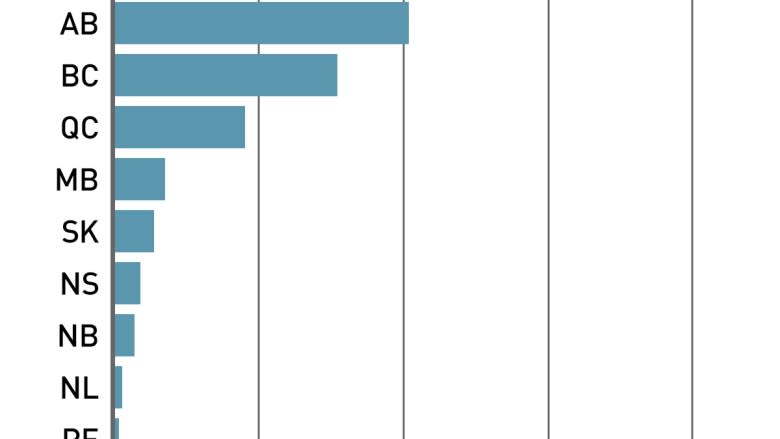

In the 2014 tax year, half of the 6,000 high-income non-taxable returns were filed by Quebec and British Columbia residents. Hundreds more came from Ontario and Alberta. More than 450 returns were submitted by citizens working out of country.

According to the most recent CRA data available, the majority of Canadians who qualify as earning these high incomes would usually be paying between $24,100 and $157,000 in federal and provincial taxes.

Every year, one out of three income tax returns filed in Canada is considered non-taxable, meaning the tax payable amounts to less than $2. Almost all of them are filed by low-income residents earning less than $15,000 a year.

So how did thousands of high earners manage to bring that bill down to zero?

CBC News asked three fiscal policy experts to explain. All of them pointed out that these Canadians represent a minuscule fraction — less than 0.1% — of the 27.5 million income tax returns filed every year in Canada.

But two of them hinted at a larger picture, one in which rich and fiscally savvy taxpayers — most of them owners of corporations — claim most of their earnings as business and investment income in order to benefit from a combination of credits and lower their tax rates.

"Our tax system is overly complex and probably benefits people who hire lawyers and accountants to work for them … lower-income people don't have that option," says Michael Veall, an economics professor at McMaster University who has spent 30 years studying Canada's tax system.

Last year, he co-authored a study that found nearly half of high-income Canadians are business owners. He says this allows them to write off most of their income "through their corporations and not pay taxes immediately."

That strategy unlocks a trove of "special deals made for business and investment income," explains Michael Smart, who teaches economics at the University of Toronto.

"Those kinds of income are based on lowest tax rates overall, typically less than you would pay on your salary or wage income as an ordinary Canadian. When you add all of them up, you allow taxpayers to be smart about how to exploit this system."

Veall says provisions like capital gains deductions allow investors to write off half of the profits they make from selling stocks.

He considers it too generous. "Most people would feel differently about a capital gain made by somebody who bought a stock today, sold it a month later and made a big amount of money on that. Most people would think that should be fully taxable. But what about someone who bought the stock 30 years ago and is selling it now? Other tax systems in other countries have made fixes for this."

Capital gains were among the most popular deductions with high income earners in 2014, with an average of $131,000 claimed for each taxpayer.

Smart says there are other tax preferences that benefit the richest and allow them to lower their taxes "to a degree most Canadians would consider surprising and unfair," like the exploration and development deduction for investments in the oil or gas industry.

According to the CBC News analysis, tax filers who earned $250,000 or more in 2014 are behind 70 per cent of the amounts written off under that deduction, with an average of $33,000 each.

But CIBC managing director Jamie Golombek has a completely different explanation as to why some high income taxpayers pay zero taxes. He says they likely are ''self-employed business people'' who lost money during a previous tax year and carried that loss over.

''If I had to guess, I would say the primary reason for that is because of our system of loss and carry-forwards. It is a complex system, but the general rule is that it would be unfair for me to pay taxes on the money I made this year, if I lost the same amount of money last year.''

He also points out the available CRA documents don't allow for tracking every individual return year over year, making it difficult to verify if an investor deducted a loss or gain over time.

Once these business-related credits and deductions are applied, high-income taxpayers can use another item to lower their tax rates even further. "Charitable contributions play a big part for taxpayers that have a low overall tax rate," says Smart.

According to the CBC News analysis, more than half (53 per cent) of the amounts deducted as a charitable donation or a government gift in the tax year 2014 came from Canadians earning $100,000 or more. They wrote off more than $5 million, or about $4,300 each.

Smart stresses he doesn't know how taxpayers manage to avoid paying taxes completely, but "if you combine the various different loopholes in the system, the alternative minimum tax is supposed to kick in and guarantee that every taxpayer's overall tax rates is about 15 per cent of their total income. There are a few exceptions to that, and one is charitable contributions."