“The Numbers Are Staggering." Why New York Doctors See No End In Sight

As the head of the clinical labs at Northwell Health, Dr. James Crawford was watching the coronavirus pandemic barrelling down on New York earlier than most anyone in the state. Now that it’s here, Crawford has a glimpse into the future of the pandemic in New York—and what he sees isn’t good.

Crawford sits atop a sea of data generated by the giant network of labs he oversees: The Northwell Health system, which includes 23 hospitals and nearly 800 outpatient facilities, serves over 2 million patients every year in an area that covers swathes of Manhattan, Queens, Staten Island, Long Island, and Westchester County. By Crawford’s calculations, Northwell’s labs have run 28 percent of all of New York state’s coronavirus tests—and 2 percent of the world’s total.

All that information gives Crawford clues about the shape of the pandemic to come. “The data will begin to show when we have turned a corner,” Crawford told me. “And we haven’t yet.”

Northwell began testing relatively late in the coronavirus pandemic: at 5 p.m. on March 8. That was when they received the requisite permission from both federal and state regulators. (Unlike clinical labs in the rest of the country, New York labs need not merely federal approval, but also that of the state government.) By then, 92 cases of COVID-19, the illness caused by the novel coronavirus had been diagnosed in the state. To Crawford, that meant one thing. “The data showed that the virus was already circulating in the New York area,” Crawford says. The testing was just playing catch-up.

Across the country in Washington state—which was then the seat of the country’s biggest COVID-19 hotspot—testing had been underway at the University of Washington, with whom Crawford was in regular contact. Doctors there were noticing an 8 percent positivity rate—that is, 8 percent of all the coronavirus tests they ran came back positive. In the world of laboratory science, that was considered extremely high. But when Northwell labs ran their first batch of tests on 20 samples, five came back positive, a 25 percent positivity rate. This was an astonishingly high—and frightening—number.

In the weeks that followed, Northwell tried to keep up with the surging demand for tests in New York state by bringing more and more testing equipment online, machines that could run far more tests at a time than Crawford’s scientists could on their own. Just like his colleagues at the University of Washington, Crawford’s labs began testing thousands of patients a day. In Seattle, the high positivity rate didn’t budge, always falling somewhere between 7 and 9 percent. But in New York, the positivity rate in Northwell’s labs didn’t stay flat—it surged.

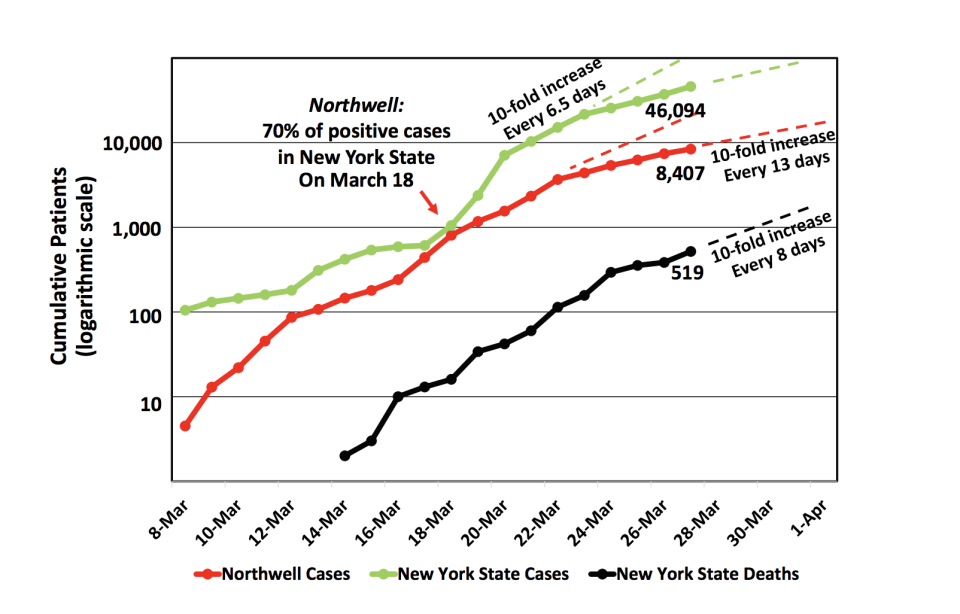

The picture that emerged was alarming. On March 18 alone, Northwell diagnosed over 800 cases. It was the vast majority of New York’s confirmed COVID-19 cases that day. That’s when, Crawford says, “it became apparent that Northwell was the epicenter of the epicenter.”

Worse still, the more tests Crawford’s labs ran, the higher the positivity rate climbed. By March 22, Northwell’s lab had increased the number of coronavirus tests it ran 30-fold. In that same period, the lab’s positivity rate jumped from 25 percent to 48 percent.

By Saturday, March 28, the rate was a jaw-dropping 67 percent.

“The numbers are staggering,” says Crawford.

Of course, the rate is impacted by who is being tested. At Northwell, like in other New York healthcare facilities, that’s people who display symptoms of COVID19: fever, cough, difficulty breathing. These patients could have any number of underlying diseases, like bronchitis or the flu or even lung cancer. The fact that the coronavirus test over half of people with these symptoms is coming back positive reflects the grim reality: the thing that’s making most people ill in the New York metropolitan area right now is the coronavirus.

I wanted to see if other New York clinical labs were seeing what Crawford was seeing at Northwell, so I called Dr. Jenny Libien, the chair of the pathology department at SUNY Downstate, which runs a hospital in east Flatbush, Brooklyn. She said that though they have far fewer patients than Northwell, SUNY Downstate’s numbers look about the same: Depending on the day, somewhere between 50 and 70 percent of all tests come back positive. Two-thirds of those being treated at Libien’s hospital, she says, are COVID-19 patients. Forty people are on ventilators. The hospital’s morgue is full. “I’ve never seen anything like it,” she says. On some days, her lab’s positivity rate has hit 80 and even 100 percent. “I know we’re just seeing the sickest patients in the hospital, but I think it means that the virus is widespread, yes,” Libien told me.

It probably also means that if you live in New York and you’re showing signs that might be consistent with the cold or flu, chances are dwindling that that is what you have. Crawford says the positivity rate for a standard flu test is now down to 15 percent at Northwell. “If you’re symptomatic, and someone sticks a swab up your nose,” Crawford says his data shows, “it’s an even bet that that you’re going to be COVID-positive.”

"We are chasing the virus," Crawford says, "and the virus is getting ahead of us."

As cases of the seasonal flu plummet, Libien says, it’s growing easier to clinically diagnose those suffering from COVID-19. “The real take-home is that if somebody has symptoms that are compatible with COVID, like a sore throat and a cough,” says Libien, “they most likely have COVID.”

Here’s what else it means.

Northwell’s astronomical positivity rate—nearly 70 percent—across such a wide swath of the greater New York area indicates that the virus has been spreading and reproducing for weeks under the radar, and we’re only seeing a fuller picture now. “The fact that our percent positives have climbed steadily to me means that we are chasing the virus, and the virus is getting ahead of us,” Crawford says. “It means that the virus is moving through our population and we are jogging after it.”

It also means that far more people than we think have been exposed to the coronavirus in New York—and are likely actively spreading it. “It is not a given that everybody in the New York area is infected with the virus, symptomatic or not,” Crawford explains. “But I think it is a given that anyone you interact with could be someone who could give you COVID, because COVID can jump before someone becomes symptomatic.”

Because it’s only the sickest people that have been tested in New York, Libien says, it gives us a very limited picture of the infection rates in the wider community. “Take whatever your testing numbers are and multiply them maybe by 10,” Lieben says of the prevailing conventional wisdom in her field. “And that’s probably your number of people that are infected.”

I asked Lieben if this essentially means that everyone in New York has the coronavirus. “No,” she says, “but I treat it like everybody has it.”

As for Governor Andrew Cuomo’s hopes that the curve is slowly flattening, Crawford isn’t so sure. “When I was looking at my screen at the start of this week, we were looking at a tenfold increase [in coronavirus cases] in 6 days,” Crawford told me on Saturday afternoon. He was in his home office, crunching Northwell’s data from the week that just ended and looking ahead to the next one. The infections were increasing a little more slowly, but still increasing. “With the current curve, it’ll take 13 days to go up tenfold,” Crawford explained. “But it’s still going up. And that’s still tenfold. Thirteen days. OK. If it’s the 28th today, 13 days from now is, what, April 10th. And so April 10th, are there going to be ten times more cases in the state of New York?”

Because the number of coronavirus infections is still rising in a logarithmic progression, Crawford worries that means there’s no way for the testing capacity to keep up, even for a giant like Northwell. They increased capacity 30-fold in March, and they could double what they are doing now, but they can’t increase another 30-fold by the first week of April. What Crawford predicts is that the testing won’t keep pace with the virus’s course—and the resulting failure to test patients will give the false impression that infection numbers are leveling off. If that comes to pass, the numbers we see won’t mean that the disease is slowing, just that our ability to plot its progress is lacking. “Potentially the curve could fall off simply because we don't have sufficient testing capacity to keep up with the log 10 curve,” Crawford says. For now, though, “it’s still an upward slope. We still need the Javits Center,” referring to the temporary hospital FEMA is building in the Manhattan convention center.

“This is a moment in our careers where service is measured not by the hour, but by the minute,” he says. “This is moving so fast.”

Julia Ioffe is a GQ correspondent.

How one young doctor at a Seattle lab tried to get out in front of the coronavirus crisis by inventing his own test. And why the absurdity of his struggle should make us all afraid.

Originally Appeared on GQ