Oil, politics and human rights: A look back at Talisman

Lloyd Axworthy still has a bitter taste in his mouth when talking about Talisman Energy and its role in Sudan during the country's civil war.

A decade removed from operating in east Africa, Talisman, which will soon disappear from Canada's corporate landscape, will remain inextricably linked to its contentious time there. For Axworthy, Canada's foreign affairs minister in the late 1990s, a look back at Talisman means revisiting its stay in Sudan, which he says deserves a prominent, if inglorious, place in its epitaph.

- Click on the video for a look into the CBC Archives, which includes a federal government warning to Talisman in 2000, protest coverage at a company's AGM and talks of a sale in 2002.

Axworthy recalls urging the Calgary-based company to clean up its act and stop contributing to the brutal violence in the African country.

"I was just frustrated," said Axworthy about his conversations with then Talisman CEO Jim Buckee. "He was basically just saying this is the way the world works there and we are not particularly bad guys compared to what others are."

Talisman Energy will soon enter the history books as the company's sale to Spanish energy giant Repsol is expected to be finalized in the coming months. No decision has been made whether the Talisman name will disappear or continue as a subsidiary of Repsol.

The legacy of the company is also up for debate. Is it Canada's most controversial oil company?

"Controversial would be an understatement," said Axworthy.

According to a high-level report by Canadian diplomat John Harker in February 2000, oil royalties flowing to the Sudanese government from a Talisman-run oil play were found to be exacerbating the country's civil war. That report forced Canada's foreign affairs department to jump into action. The government wanted Talisman to make sure it was not complicit in the human rights abuses happening in Sudan. Instead of fuelling the fight, Ottawa wanted the company to leverage its position to help bring about a ceasefire.

"It was very hard. There was stonewalling on the part of Talisman," said Axworthy. "They would talk to us, we would have meetings in Ottawa, but our limitations were that we really didn't have the kind of authority that we needed. Economic legislation can only be triggered, in terms of sanctions or response, if there was a United Nations decision about that.

"There was push back as you might expect from the oil patch about what we were doing. I certainly felt some of the political repercussions of that."

Talisman entered Sudan in 1998, acquiring a 25 per cent stake in a consortium operating in south Sudan's Heglig oil field. When Buckee would face questions and accusations about his company's operations in Sudan he often repeated the lines "we're just an oil company" and "I am a businessman and I intend to generate wealth." Another of Buckee's phrases, "if the rocks makes sense," neatly summed up how the globe-trotting company privileged a play's geology and production potential over political and social issues on the ground.

Buckee's approach wasn't without merit as Talisman repeatedly beat expectations for revenue and profits.

However, financial results were only part of the equation. During the civil war, for instance, the Sudanese government was found to be attacking civilians from an air field that was supposed to be used only for oil-related air traffic. The Harker report stated Talisman was turning a blind eye to the situation and acquiesced in allowing the military to use the airstrip.

"The report raised some very serious questions," said Axworthy. "In a situation of that kind, nothing can be totally conclusive. It's always difficult to gather full evidence especially when you are dealing with an area where there is conflict and there is hard access."

James Rubin, a spokesman for the U.S. state department, said Talisman's development project had "provided a new source of hard currency for a regime that has been responsible for massive human-rights abuses and sponsoring terrorism outside Sudan."

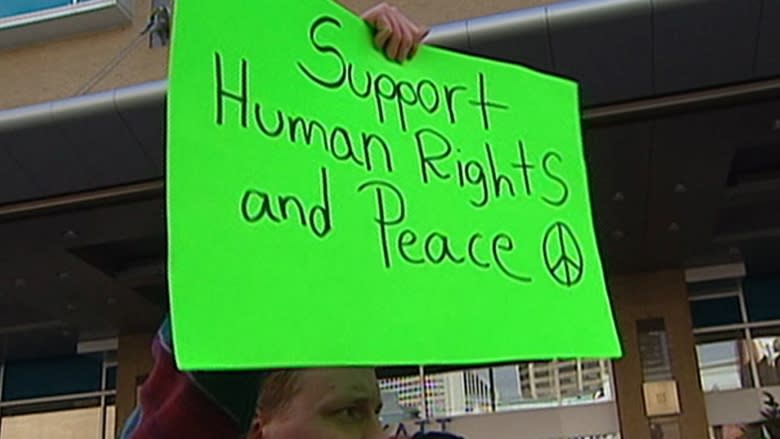

Back at home, Talisman soon found protesters on its door step. One of the groups that opposed Talisman was comprised of church leaders. Rev. Bill Phipps, former moderator of the United Church of Canada and a Calgarian, called for a halt to oil production until the civil war ended.

"In an era of globalization where we seem to be able to develop complicated rules for economic exploitation and development, surely to God we have the brains to figure out how to declare a moratorium on oil production in order to save lives," he said.

After an American investigation of the western region of Sudan known as Darfur, U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell said in 2004 that there was a pattern of atrocities including killings, rapes and burning of villages. The U.S. concluded that genocide had occurred and may still be occurring in Darfur.

Sudan's president Omar al-Bashir was eventually charged with genocide.

Go to the oil

Canadian energy companies operate all over the world in dozens of countries. Often international delegates will travel to Canada to try and lure companies to expand into their countries. The attractive commodity a Canadian company often brings to the table is the engineering know-how that allows complicated oil plays to be unlocked and resource wealth to flow. That's what happened when Talisman arrived in Sudan. The Heglig oil field only became a lucrative property after Talisman rolled up its sleeves and went to work on the play.

Still, not everyone sees Talisman's time in Sudan as a company-defining event.

"For whatever reason, Talisman turned into a hot button," said Fred Pynn, a veteran analyst and investment fund manager in Calgary who is currently with Richmond Equity Management. "Oil companies will operate in other countries that have even worse human rights records than Sudan did, but if it is not on the radar screen of the activists, then you can go along and mind your own business."

Pynn points to Nexen as one former household name that still managed to fly under the radar. According to the Calgary Herald, the energy company — now owned by a state-run Chinese oil company — recently pulled out of beleaguered Yemen, a country plagued with violent clashes between government forces and rebels for several years. The newspaper report stated Nexen had produced more than 1.1 billion barrels of crude oil in the southwestern corner of the Arabian Peninsula since its arrival in 1987.

"Nobody was marching around saying Nexen was a terrible company," said Pynn.

For international oil companies weighing country risk is part of the job. Different companies vary in their appetite for risk when looking at a move into a new jurisdiction. Those risks are weighed against the amount of oil or gas in the ground and the projected rate of return. In countries where there's conflict or the potential for strife, determining the amount of risk isn't always a straightforward call.

"They end up going to some pretty sketchy places and who knows were the money actually goes at the end of the day. Roads or the military? A lot of it ends up in Swiss bank accounts presumably," said Pynn.

Arguably Canada's most cosmopolitan oil company, Talisman was comfortable operating in places where other companies wouldn't. Such decisions, however, weren't without consequences. In Sudan, for instance, aid workers claimed oil money was used to buy weapons for a government accused of genocide. For its part, Talisman denied the accusations, saying the the royalties of its oil project only helped the struggling nation construct roads and hospitals.

Pynn describes the Talisman years in Sudan as a blip — an episode many have forgotten about.

"I don't think they have a black eye as a result of it," he said. "The focus is actually on the asset itself, not the company or its management, and that's the case with Talisman."

More recently, Talisman's legacy will be tied to the struggles of its assets in the North Sea. Along with low natural gas prices, those problems sent Talisman's shares on a multi-year slide. Hal Kvisle, former head of TransCanada Corp., was brought on board to clean up the company for a sale. After a few years and some unsuccessful attempts, Talisman locked down a deal with Repsol that will see Canada's fifth largest independent oil company end up in Spanish hands.

Ironic twist

Repsol won't have to worry about Sudan, which Talisman sold in 2002. The rewards, the company eventually found, weren't worth the cost.

"Talisman's shares have continued to be discounted based on perceived political risk in-country and in North America to a degree that was unacceptable for 12 per cent of our production," said Buckee in a company statement. "Shareholders have told me they were tired of continually having to monitor and analyze events relating to Sudan."

Talisman's Sudanese oil interests were bought by ONGC Videsh Ltd., a subsidiary of India's national oil company, for $1.2 billion. The company would divert its attention to its remaining assets in Canada, Indonesia, Malaysia, Vietnam and the North Sea.

While oil operations in Sudan prolonged the country's violence, Talisman's exit may have caused more harm than good. Talisman was a part of a consortium including a wholly owned subsidiary of the China National Petroleum Corporation, a wholly owned subsidiary of Petronas — the national petroleum company of Malaysia, and Sudapet Ltd. — the national petroleum company of Sudan.

"In an interesting irony, in the consortium that Talisman belonged to, they probably had some restraining impact, because certainly when they sold out, the new owners, particularly the Chinese state oil company had no conditionality whatsoever," said Axworthy. "So in effect, the absence of Talisman probably did not help try to restrain the actions of the Sudanese government."

Despite Axworthy's admonishments, the Canadian government never sanctioned Talisman, a lack of action that was criticized by human rights groups and described as "a knife in the back to the victims of Sudan's brutal war."

Before leaving office, Axworthy wanted a review of existing Canadian legislation regarding corporate responsibility, but it wasn't conducted. To this day, Axworthy says not having that review is the one disappointment he carries from his time at the head of foreign affairs.

"The problem was that we really didn't have any effective machinery in the Canadian government to actually apply a fairly strict framework or rules or standards nor do we really internationally," said Axworthy. "It's still one of the weaknesses. There is not much that can be done from a point of view of setting very strict responses or demands or requirements."

While Talisman eventually skated away from the Sudan controversy, Axworthy still can't believe how the company continued to go years without acknowledging any type of connection to the civil war.

"I think it was just a total indifference. That's what bothered me. The attitude that came out was like, 'So what?'" said Axworthy. "There was no sense that when you are a Canadian company working abroad, you are seen as a representative of what Canada stands for."

In 2009, Ottawa created a special counsellor to look at corporate social responsibility related issues overseas. The counsellor position, however, has been vacant since October 2013.