How one art museum has reckoned with race and its past

For museums to move toward a more equitable future, it is instructive to look back.

At some institutions, that work was in progress before the pandemic.

Last October, MOCA began an informal audit of its collection. "MOCA is committed to a more equitable collections and acquisitions program," said Director Klaus Biesenbach, "and this includes increasing the representation of works by women and BIPOC artists, including Chicano and Latinx artists."

This month, MOCA announced a list of new acquisitions that includes Black artists such as Lauren Halsey, LaToya Ruby Frazier and Senga Nengudi as well as Latino artists, including Carmen Argote, Gala Porras-Kim and Harry Gamboa Jr., cofounder of the influential 1970s art collective Asco.

Across town, UCLA's Hammer Museum is engaged in a similar accounting. "It's looking at how the collection breaks down," says Hammer chief curator Connie Butler.

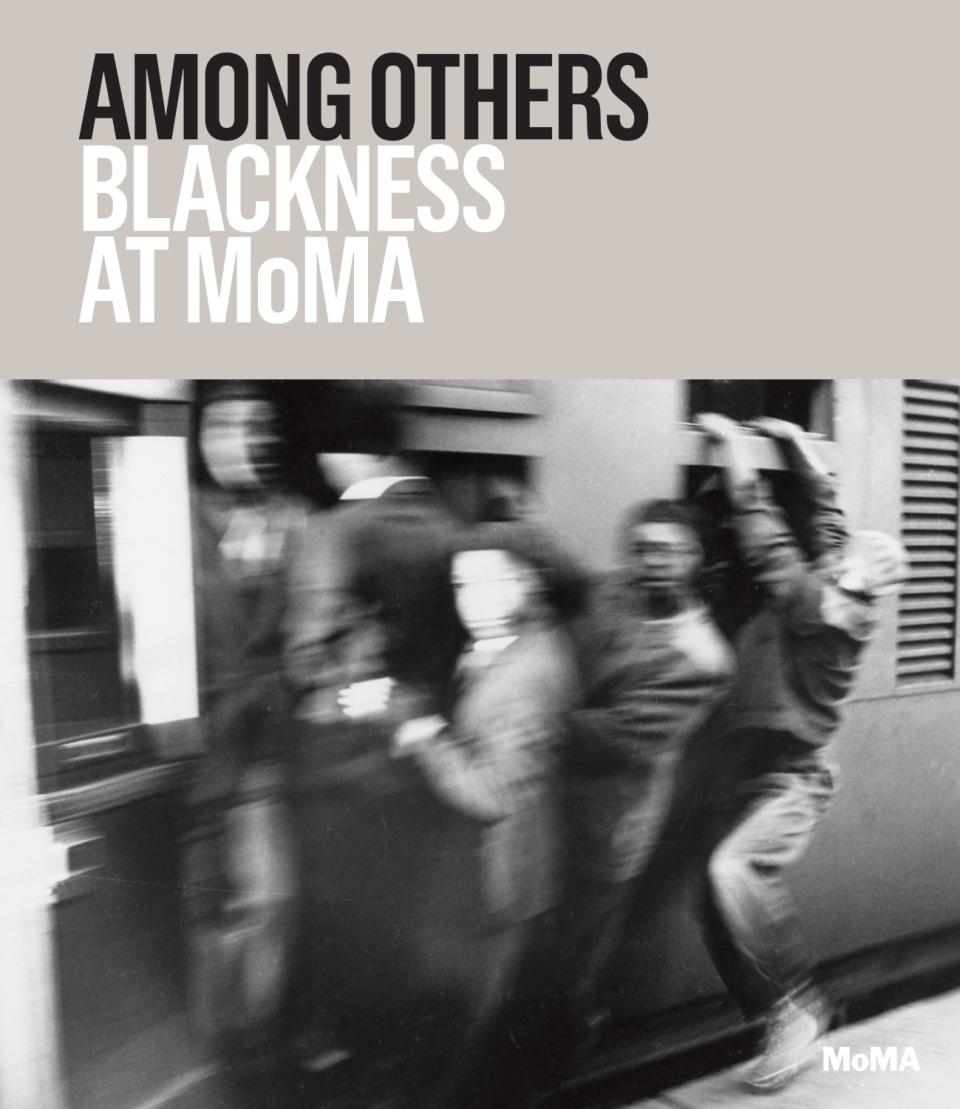

One of the more interesting examples of institutional self-examination has emerged out of New York's Museum of Modern Art. Last fall, the museum published "Among Others: Blackness at MoMA," a phone book-sized tome that serves as a frank examination of that institution's legacy in displaying, acquiring and otherwise engaging work by Black artists. It also serves as a compelling art catalog.

Curators Darby English and Charlotte Barat combed through a wealth of internal memos and correspondence to provide a frank assessment of how the museum has tackled issues of diversity in the galleries and within its ranks since its founding in 1929. The picture, as is to be expected, is not always pretty.

It's a history, they write, that alternated "between moments of pioneering initiative and episodes of neglect and worse."

It took MoMA five years after its founding to show a work by a Black American artist: Earle Richardson's 1934 social realist canvas, "Employment of Negroes in Agriculture," which depicts cotton workers in a field — a painting displayed in a group exhibition under the New Deal's Public Works of Art Project. English and Barat say it's telling that other Black artists' works that engaged themes of Black modernity were available, including a portrait of Booker T. Washington, but the museum chose not to show them.

The next year, MoMA devoted its galleries exclusively to the work of Black artists. "African Negro Art," which displayed hundreds of objects primarily drawn from West and Central Africa, was an important step in displaying African art as art not ethnography. But if the 1935 show "succeeded in presenting its constitutive objects as works of art," write the curators, "it continued to understand them as the production of an undifferentiated ensemble of Black makers, in stark contrast with the singular producers of modern masterpieces."

In this way, the book takes a historical trip through MoMA's history, highlighting moments of achievement but also episodes of racism and rank paternalism.

"One of the most important lessons for me is that there is so much in the book that is three steps forward, two steps back — or something progressive being done and then being undone," says Ann Temkin, MoMA's chief curator of painting and sculpture. "We were all surprised to see how much did happen and how much almost went in a certain way and either people weren't brave enough to make that final decision or it wasn't followed up on."

There are some especially intriguing, relevant-to-today sections as "Among Others" moves into the 1970s. The book documents the struggles of isolated Black curators — like Howardena Pindell, now better known as a multimedia artist — forced to contend with white institutional structures that had tasked themselves with devising ways to show work by Black artists.

"I personally question the depth of feelings and sensitivities one develops without direct experience," Pindell wrote in a memo at one point.

Particularly eye-opening are the failures within the museum's department of architecture and design.

An essay by architect and scholar Mabel O. Wilson of Columbia University's Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation examines MoMA's track record in that area. It's slim. As Wilson notes, MoMA didn't accession a work by a Black architect or designer until ... 2016.

The object in question was a View-master (model G), a mass market stereoscopic image viewer developed by industrial designer Charles Harrison in 1962.

Since the project launched, MoMA has acquired important works by artists such as Aaron Douglas and Gordon Parks.

It has also provided the public an accounting of internal dynamics — available for all to see in black and white.

"We are all historians," she says. "To think about these issues in the context of the present moment and the future, it was absolutely necessary to have a sound grip on our past."

On its own, "Among Others" won't fix MoMA's structural issues. But it's a beginning. Hopefully it inspires similar accounts at other museums.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.