How one Sask. university is working with elders to further scientific research on traditional medicinal plants

The First Nations University of Canada (FNUniv) in Regina is approaching the research of medicinal plants in a unique way — by pairing students with elders and knowledge keepers who know these traditional plants intimately.

The pandemic has had a major impact on universities, with many international students not having the ability to physically attend school in Canada.

This can be especially difficult for international students in the sciences as laboratories are not always available to those attending classes virtually. But FNUniv has found innovative ways to work with these students.

Biotechnology researcher Ana Karime Arellano Franco, a 24-year-old undergraduate at Instituto Tecnológico de Monterrey in Mexico, is one of those students. She recently worked remotely from home in the department of Indigenous knowledge and science at FNUniv.

The Regina campus partnered with Arellano Franco through the Mitacs Globalink Research Internship program, which connects universities with students from abroad.

Arellano Franco has long been fascinated by traditional Indigenous plants and their medicinal properties. That's led to a desire to learn more about plant chemistry.

You won't find her buying bagged tea at her local supermarket. Instead, she uses plants to make her own tea.

Arellano Franco says medicinal plants are important to her because so many people in Mexico have Indigenous ancestry.

"To this day, Mexican indigenous medicinal plants ... this knowledge has been passed through generations. It came to my grandmother, to my mother, and now I am interested in it."

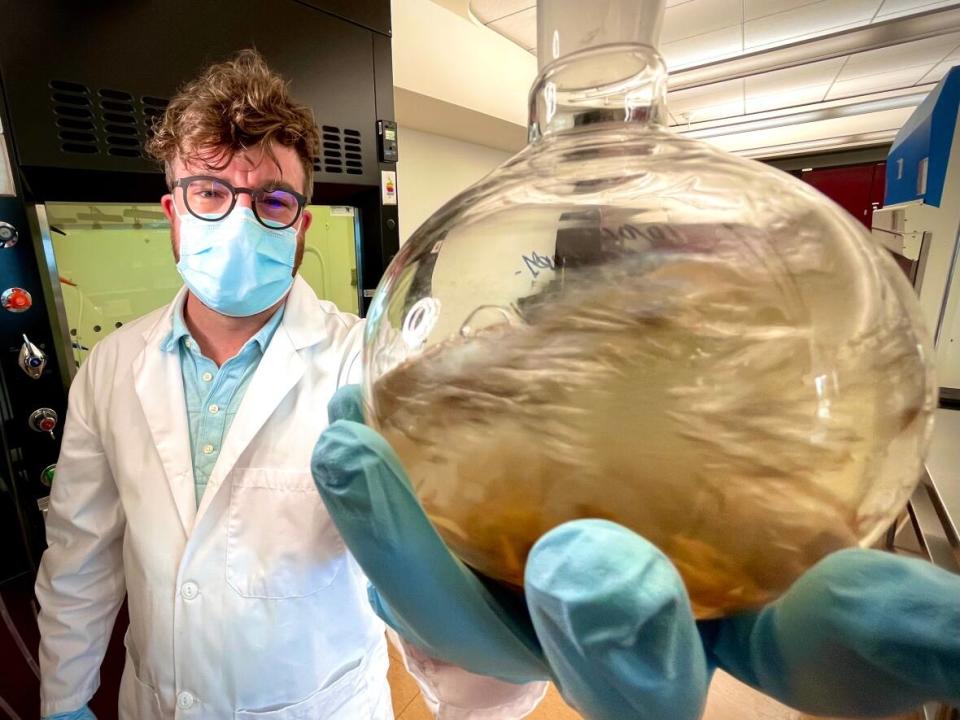

Arellano Franco worked virtually with Dr. Vincent Ziffle, assistant professor of chemistry at FNUniv, on her project. She was also guided by an elder from Saskatchewan.

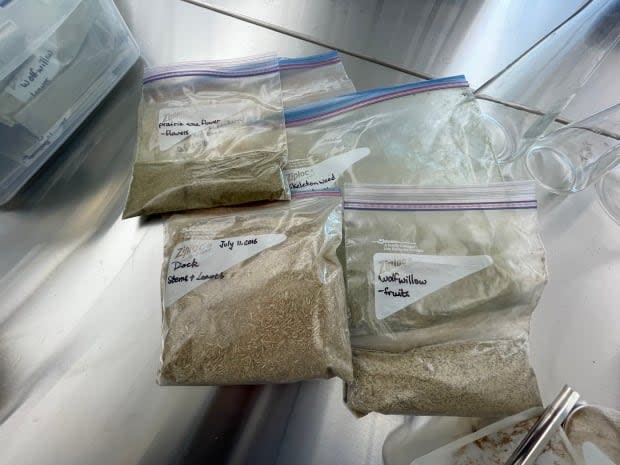

The student's work involved identifying, extracting and analyzing the medicinal properties of seven common plant species, including wild sarsaparilla, Canadian mint, prairie rose and purple coneflower.

"I am emphasizing the molecules we're looking for in these plants and how we can synthesize them using organic chemistry in a respectful way to the First Nations," said Arellano Franco.

The 'respectful' component of this research is extremely important, she says.

"It means to emphasize how they were being used in the past. For example, purple coneflower has been used to treat throat infections, and it's being researched for the same purposes, for its antimicrobial purposes," said Arellano Franco.

"But we need to say First Nations have been using these plants in this way, and that is why we are researching them. And how can we use these molecules without exploiting them?"

The science

Initially, Arellano Franco was supposed to conduct her project in the university's Regina organic chemistry laboratory. But due to the pandemic, her focus shifted to completing a survey of the seven identified plants from home in Mexico.

Her findings will form the basis for further analysis in the lab, and an on-site group of students will extract plant molecules, according to Ziffle.

"What we're looking at is underappreciated Indigenous medicinal plants and their secondary metabolites, including alkaloids and other antioxidants," said Ziffle.

"It turns out that some of those interesting molecules are able to fight cancer ... or to simply be good antioxidants, which we also know is very important even in hindering the progress of cancer, from preventing it from getting its claws in."

Ziffle says it is not unusual for the science world to look to the natural world for inspiration, but FNUniv differs in its research approach.

"First and foremost, the goal here is to do something unique, and that's to properly acknowledge Indigenous knowledge in the context within a chemistry or medicinal plants biology paper. And so we're always trying to shine a light on that and uplift those knowledge holders or keepers," said Ziffle.

Knowledge keepers

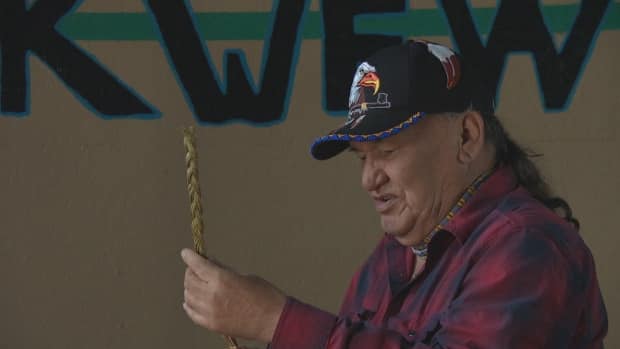

For her project, Arellano Franco consulted with Elder Archie Weenie from Sweetgrass First Nation, located 26 kilometres west of North Battleford, Sask.

Weenie has worked with FNUniv for many years, and considers plants and nature to be healing.

"I was lost one time when I was young. I went back to my roots. And I've been walking that way ever since ... I carried sweetgrass. That was my elder. I had nowhere to turn. It took a few years before I kind of rejuvenated my spirits. To be strong enough to go back into my community. This is what I understand, the sweetgrass," Weenie told the CBC at his sweat lodge in Regina, following a ceremonial smudging.

Weenie says that many Indigenous people are hesitant to share their knowledge of medicinal plants.

"Say I talked about something so powerful, then you are trying to grab it, misuse it. So old people are careful what they reveal," Weenie said.

"If it's going to help the individual and they're sincere about it, I will share."

Weenie says it's good for the students in the program to understand him and where he comes from.

"When I went to school, they were condemning natives all the time. And they weren't true. I try and help to change stuff," he said. "To know that we're not that evil people they put us to be. It's good to love each other. Respect. Forgive. It's so hard to do, but we got to keep it up to make things better for the future."

As for his experience working with people in the sciences, Weenie says he enjoys it.

"It's good. It gives me something when I work with professors with their degrees. Well, I've got my own degrees too, in this way of life. But mine is all natural. My Bible is the mother ... the universe."

Creating a symbiotic relationship

Ziffle says he makes sure he asks the elders to share their traditional plants knowledge in a respectful way, which includes following proper protocol and providing tobacco. He says this is an important thing to teach his students.

"But I've also had conversations where an elder has said, 'OK, enough of that for now. Enough of these teachings. What I really want to know about are the ingredients within these plants or the molecules. What do they look like?"

Ziffle says this curiosity is very rewarding for him as a teacher and a lover of science.

"It's humbling to have that type of audience and to have a receptive audience like that. And so it's very exciting."

Ziffle says FNUniv has spent years building relationships with the elders.

"We certainly wish to return the information, the data, what we discover back to the communities that have so kindly accepted us and invited us to go on picking sessions, on medicine walks, and attend ceremony."

When students finish up classes, Ziffle says their reviews usually say that the best part of the semester was when an elder attended the class.

The professor says working with Indigenous knowledge keepers has also affected the way he teaches.

"I've learned a lot from the oral traditions of Indigenous storytellers, and I try to approach my teaching in chemistry in a similar way because I think I've learned better through storytelling ... and certainly our students appreciate this too. It allows us to hold onto that information, perhaps in a better way."