How one stone gave a Halifax-area park heritage status

A hulking, rocking chunk of granite that's been attracting visitors for two centuries and is rumoured to have caught the attention of royalty has had its historical importance to the Halifax area set in stone.

The Halifax Regional Municipality awarded heritage status last week to the Rocking Stone and the surrounding Kidston Lake Park in the community of Spryfield.

"It's such a unique feature," said Arthur Kidston, whose family once owned the land where the Rocking Stone sits.

"There are a lot of large granite rocks in the area, but none are as large as this — nor do any of them rock."

The Geological Survey of Canada has said the boulder, left behind thousands of years ago by a melted glacier, could be the largest rocking stone in the world.

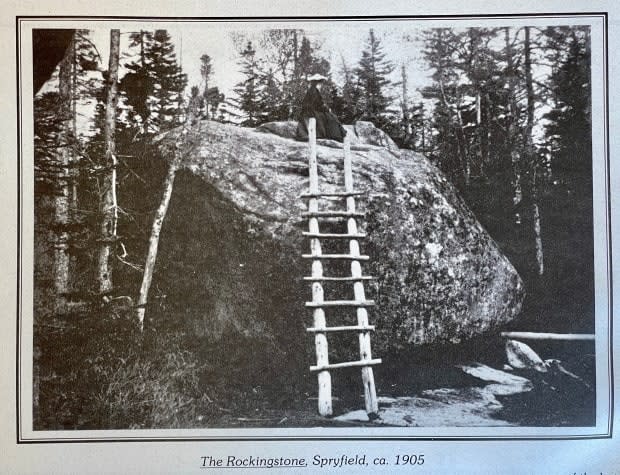

The first published description of the boulder was in the Acadian Recorder newspaper in Halifax, which described the Rocking Stone in 1823 as a "wonder of nature" and noted it could be "set in motion by a child of 12 years of age," according to a staff report for the Halifax Regional Municipality.

Kidston connection

Kidston's connection to the Rocking Stone goes back generations.

The stone was on the family's dairy farm for over 100 years before Kidston's father donated a portion of the land, including the unique boulder, to the former Municipality of the County of Halifax to operate as a public park.

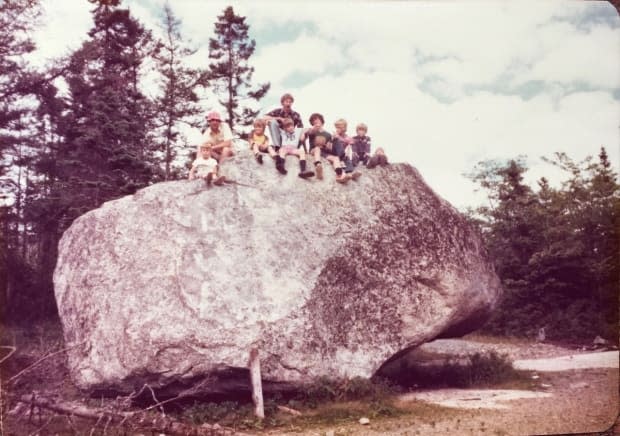

"Over the years we have brought so many people to come visit the rock whether it was for a picnic or picture," Kidston said.

"It's a part of our heritage and lifestyle."

The boulder has also lured some notable visitors.

Former British prime minister Bonar Law, whose mother was a Kidston, played on the rock during his childhood. Kidston said it's rumoured that King George V visited the stone and had tea with his grandfather.

The municipal staff report said the Rocking Stone has long been a "well-known geological curiosity," measuring six metres long, four metres wide and not quite three metres high. It's unknown just how much it weighs, but estimates range from 147 tonnes to 431 tonnes, the report noted.

Rock no more

Increased usage of the area has had some detrimental effects on the stone's rocking capabilities.

A group of soldiers from the Halifax Garrison reportedly once shook the stone so vigorously that it settled slightly, but visitors could still get it rocking with the assistance of the lever.

After the land was given to the municipality, the lands bordering Kidston Lake were used as the site for the Timberlea Lumber Company. Due to an increase in debris getting stuck below the rock, the stone was rendered immobile.

It stayed that way until community efforts in the 1990s got Kidston's favourite landmark rocking again. The fire department hosed out the debris, and visitors could witness the magical movement with the help of a lever.

But Kidston said there's still room for improvement.

"It might be time for them to come and do it again," Kidston said. "Let's put some of the rock into that rocking stuff."

Coun. Patty Cuttell said the heritage decision was an important step in protecting both Kidston Lake Park and the Rocking Stone from increased pressure of development in the area.

"I think it's really important that we recognize the heritage value of the park so that we can preserve the stone in its original state, which is such an important part of the Spryfield story," said Cuttell.

"Protecting it right now doesn't only preserve its integrity, but it also will help inform what happens around the park in the future."

MORE TOP STORIES