How one tiny N.L. town helped usher in the era of instant communication

Of all the ocean views that can take your breath away on the beach of Heart's Content, it's safe to say you wouldn't look twice at the rusty old cables that run across its rocks and out to sea from the small town — population 375 — perched on the shores of Newfoundland's Avalon Peninsula.

But 150 years ago a single cable forever changed the way the world communicated, as the first successful transatlantic subsea cable, able to send and receive telegraphed information, solidified a link between the old world and the new for the first time.

Prior to July 27, 1866, if you wanted to send a message across the ocean, it would be carried over in a ship's cargo hold. In 1865, the news of Abraham Lincoln's assassination arrived in Europe a week after that deadly shot rang out through Ford's Theatre.

But the subsea cable consigned that level of communication patience to history that July day, as a ship landed on the town's shore, bringing with it a cable that stretched all the way back to Valentia Island, Ireland. With that, the small cable station in Heart's Content became the starting point for all those 21st-century text messages now built into everyday life.

"This is where we truly began. There are some books that dub us the 'Victorian internet,'" said Tara Bishop, an interpreter at the Heart's Content Cable Museum, a small station which has gone from being a hub of communication processing to a provincial historic site, and now thrust back into the spotlight as the epicentre of the town's 150th anniversary celebrations of the event that ushered in a technological revolution.

Old-timey texting

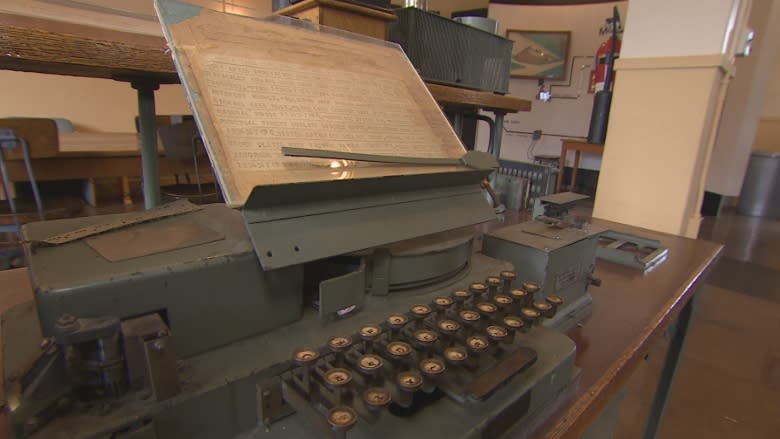

Of course, "technological revolution" had a different ring to it in the late 19th century than it does today. The first telegraphs were transmitted in a visual Morse code, using lights instead of sounds, and required three people to receive and relay the messages in a darkened room.

"It was quite a tedious process to even receive a message on this piece of equipment," said Bishop.

Despite that, the technology proved invaluable for people hungry for global happenings.

"It's like us turning on a news network and watching the ticker tape running across the bottom of the screen of news headlines or stock markets. That's what these people provided to the world," said Bishop.

It wasn't cheap, either — a 20-word message cost about 20 British pounds. But human creativity soon leapt ahead of those costs.

"These people were the first texters," Bishop said. "They were shortening words and combining words to make it more feasible to send their messages."

That transatlantic texting continued to be relayed through Heart's Content for almost one hundred years, before the station shut its doors in 1965.

Ending up obsolete

When Art Tavenor walks through the museum, the past comes to life: he worked at the station as a young man and was there until its final day.

"It was an eerie feeling, because all of this equipment stopped working and all you could hear was the three clocks on the walls," he said.

Tavenor was a technician, fixing bugs and breakdowns in the system, which had grown to six subsea cables, each capable of transmitting information at the then-lightning speed of 50 bits per second. (A little tech perspective: Bell Aliant's top home fibre-optic package in 2016 can download data at 940 megabits a second — a megabit is one million bits.)

Tavenor said he didn't snoop on people's private chats, either — most of the communication he saw came in the form of test patterns to analyze how well, or not, the cables were working. And when it was up and running, he simply processed the messages and relayed them to their final destinations, usually either New York City or London.

"If you get that much coming in, you're not really curious," he said, although history will have to take that honour system on his word.

While Tavenor said that in general citizens of Heart's Content were "in awe" of the cable station, to him and his fellow workers it was just a steady job, with no sense of its technological importance in connecting the world.

"We didn't really pay much attention, I guess. You're thinking in a different time," he said, adding he and the other workers were surprised and deflated when the day to shut the station's doors finally came.

"We had the feeling that it was going to go on forever," he said. "We didn't really realize that it was going to close. The cables became obsolete."

By the 1960s, telegraph messaging had fallen by the wayside, and the cables that linked Heart's Content to the rest of the world were disconnected, in favour of fibre optic cables that still carry telecommunications and internet traffic across the ocean today.

New life for an old technology?

At least one researcher sees a great future and a new purpose for subsea cables, hoping they could help unlock climate change mysteries so far unknown to scientists.

"The ocean is the main driver of climate change, and we need to understand the changes that are taking place in the deep ocean," said Chris Barnes, head of a United Nations joint task force on ocean cables and the former head of NEPTUNE, the world's first regional cable ocean observatory.

"Particularly the temperature changes, which are an indicator in changes of ocean circulation down there, and also what's happening when we melt the poles and that cold water comes down and starts to influence the deep ocean circulation."

So far, Barnes said, this data has been in short supply, with most of what we know gleaned from ships and buoys that skim the ocean's surface.

"We have very little information on an ongoing basis, and almost none in real time, from the deep ocean," he said.

Barnes's dream is to have sensors attached to existing undersea cables and, from those, collect all sorts of data: temperature fluctuations, sea level changes and seismic activity among them.

"This is a completely new, revolutionary way of getting a data set that's really vital to understand climate change," he said, adding that data is needed to help better guide political decision-making on environmental issues.

For now, using subsea cables for such research is just a dream. But then again, so was instant communication across the ocean 150 years ago.