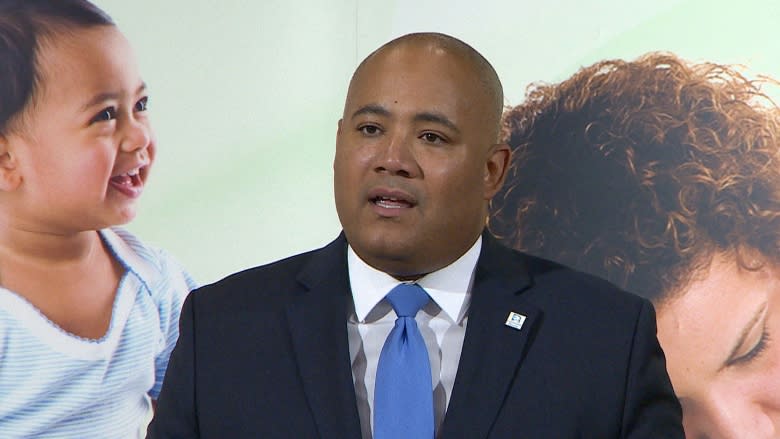

O'Neil Allen grew up in the child protection system — now he's going to work to change it

O'Neil Allen can't say exactly how old he was the day police showed up at his grandmother's apartment and took him from his mother.

"Six or maybe seven," he says.

Too young to quite remember. Too young to have any legal say in the decision that would direct his next dozen years.

And too young, he says, for anyone to ask the boy "with behavioural issues" about their decision to move him to a group home a few months later, but leave his brothers in foster care in Port Perry.

No say

Now 27, he describes in detail the day his mother was in withdrawal and began to beat his brother with a plastic broomstick, dotting his body with welts the school would later find. He says he knows they weren't safe with her.

But taking them away also kept him from his grandmother, a woman who remains a loving presence in his life, he says.

"You're just sitting there as a bystander while these people are talking about what you should do," he says. "I didn't have a choice in my [own] life until they were preparing me for independence."

But children under the province's protection may soon be given a voice.

New child welfare law

The Ontario government introduced a new Child, Youth and Family Services Act Thursday to replace a 31-year-old law governing the child welfare system. It's part of the province's work to turn the 173 recommendations from the Katelynn Sampson inquest into law after the jury identified ways in which the education and child protection services failed the seven-year-old girl.

As a former child of the system, Allen said he welcomes the proposed changes. Especially when it comes to giving children the right to make choices about their education.

As a kid, he says he went to parent-teacher nights alone. The staff at his group homes were there to make sure he was safe and fed — but they didn't help him with his schoolwork.

He moved schools so frequently he began to struggle and he says he asked to stay behind in Grade 5.

His caseworker didn't support that decision, he says. So he started Grade 6 in the fall.

"All they have to do is make sure we don't die during their shift and eat properly," he said. "They don't care if we get As or Bs. In care, it just seemed like they guided kids to be safe — and not to be who they could be."

Right to education

That's why he hopes the new legislation gives priority to a child's right to education and development

"When we leave that system our education is going to dictate our future," he said.

He knows that himself.

Allen joined a gang in high school, influenced by what he calls the "gangsterized" environment in his group home. He was expelled.

But he turned his life around after leaving when he turned 18 and joined the Voyager Project, run by Prof. Kim Snow at Ryerson University. The initiative helps kids who were part of the child welfare system improve their education.

Allen recently graduated from George Brown College's fashion program.

But what he really wants is to become a child and youth services worker, something that he'll begin studying for in the coming months.

The province may be making changes to the laws, he says, but he wants to be a part of changing the system.