Ontario makes controversial change on how to help overdose victims

The Ontario government is making a controversial change in the fight against opioid overdoses by asking bystanders to give mouth-to-mouth resuscitation to victims, CBC News has learned.

The move is stirring up an ongoing debate in the medical community about whether rescue breathing helps or harms overdose victims.

The Paramedic Association of Canada's executive director, Pierre Poirier, pushed for the change through his work on Ontario's opioid emergency task force.

During an opioid overdose the brain no longer reminds the victim to breathe, and in some cases their tongue also falls back and blocks their throat, Poirier said.

Without mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, overdose patients could be at risk of brain damage or worse because of a lack of oxygen, he said.

"The danger of not doing rescue breathing is that somebody will die," said Poirier.

'We don't actually know if rescue breathing helps'

However, not all experts agree.

Researcher and emergency physician Dr. Aaron Orkin said science shows rescue breathing is difficult to perform properly and may get in the way of a more effective option: chest compressions.

"We don't actually know if rescue breathing helps," said Orkin, who works at Mount Sinai Hospital in Toronto.

"Withholding chest compressions in someone who has no signs of life is withholding their only chance of survival."

Mouth barriers soon to be included in overdose kits

Ontario faced a spike in opioid-related deaths for much of last year. There were 1,053 fatalities from January to October 2017, compared to 694 during the same time period in 2016.

Until now, the government advised bystanders to follow the same model as the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada: perform chest compressions before giving naloxone.

The Ministry of Health confirmed to CBC News it's changing those recommendations after consulting with the opioid emergency task force, which includes public health officials, first responders, harm reduction workers and opioid users.

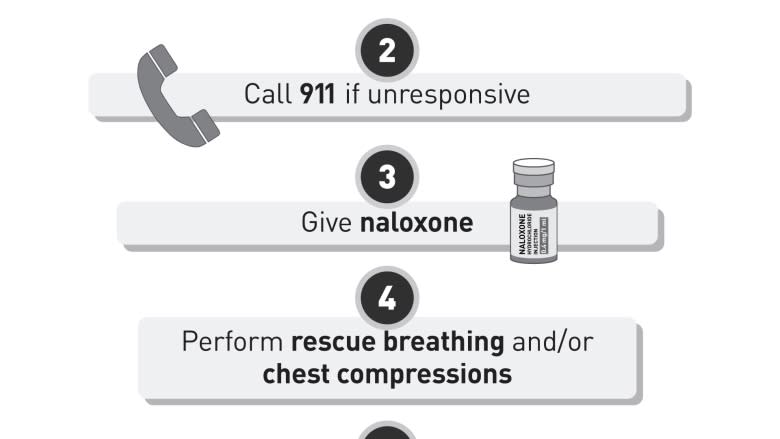

New instructions will be included in all publicly funded naloxone kits in the next couple of weeks, advising people who come across suspected opioid overdose victims to give them naloxone, then perform rescue breathing and/or chest compressions.

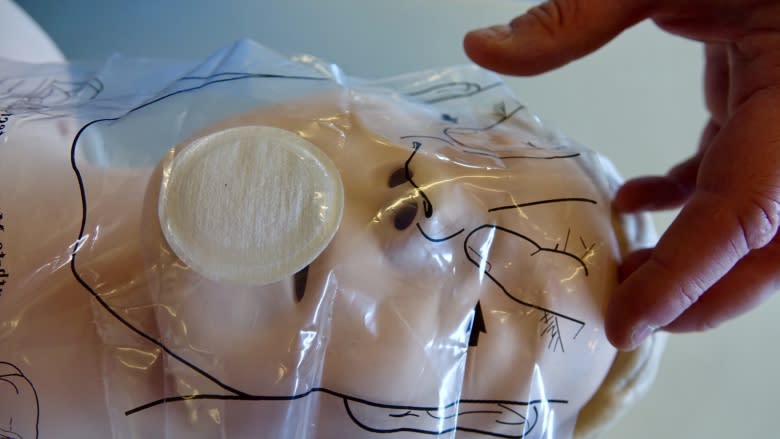

The kits will also include a plastic mouth barrier so people are less hesitant to perform rescue breathing.

Health units and pharmacies will also provide training on the new changes.

Poirier told the task force that opioid overdoses are a breathing problem, not a heart problem.

"Chest compressions are really directed toward somebody who is having a cardiac event," said Poirier. "That would be an obese 50-year-old male who has cardiac disease."

Opioid deaths involve cardiac arrest

Orkin said the vast majority of people dying of opioid overdoses in Ontario often have complex health issues, including heart or lung problems and chronic diseases, and that cardiac arrest is a factor in opioid overdoses.

"You simply cannot die from opioid overdose without going into cardiac arrest," Orkin said.

Orkin works extensively with people who use drugs in shelters and was part of the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation. That extensive review of research led to the development of guidelines adopted by groups including the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada.

Available evidence shows that whenever a person is unresponsive, whether due to an opioid overdose or something else, the most important intervention is chest compressions, Orkin said.

He would never tell someone not to perform rescue breathing, but does say it's difficult to perform properly, even for experts such as himself. It's best to keep the steps as simple as possible for untrained bystanders or they might freeze, he said.

"Expecting the general public to take on [rescue breathing] in order to address an epidemic that is sweeping across our communities, is I think really quite an overwhelming challenge," Orkin said.

Push for Ontario to adopt B.C. model

The Paramedic Association of Canada said Ontario's new recommendations don't go far enough. It's asking the province to go a step further and learn from British Columbia — the epicentre of the opioid crisis.

The BC Centre for Disease Control recommends opening the victim's airway and giving a rescue breath every five seconds, even before administering naloxone.

Michael Nolan, chief of the County of Renfrew Paramedic Service, said his team is already teaching families of known drug users in his community to perform rescue breathing first.

He wants Ontario to follow suit over concerns that while bystanders wait for the naloxone to reverse a victim's breathlessness, there could be brain damage.

"Those are precious seconds and, in many cases, minutes where the person is still going without the oxygen they need," said Nolan. "By not providing them rescue breathing in advance of the [naloxone] or in combination, they may well go for minutes without oxygen circulating to their brain."

In an emailed statement, Ministry of Health spokesperson David Jensen wrote that naloxone should be provided before rescue breathing because some people can't provide rescue breathing, and because naloxone reverses overdoses.

"There is, in the ministry's view, evidence to show that responding bystanders (who are not paramedics) may not be capable or willing to provide resuscitation in an opioid overdose situation," Jensen wrote.

"Naloxone is an opioid antagonist that can reverse an opioid overdose. It is important that someone experiencing an opioid overdose in the community receive naloxone as quickly as possible."