OPINION | Why separation is not a solution, or even a credible bluff

This column is an opinion from Max Fawcett, a freelance writer and the former editor of Alberta Oil magazine.

If at first you don't succeed, try, try again. That appears to be the logic behind Moment of Truth: How to Think About Alberta's Future, a new book from Jack Mintz, Ted Morton and Tom Flanagan that trades in some decidedly old ideas.

Indeed, many of them were contained in Stephen Harper's so-called "Firewall Letter," a 2001 articulation of western grievances that was co-signed by Flanagan and Morton.

And while much has changed in the world in the two decades that followed, little seems to be different in the ideas that Morton and Flanagan are presenting in their new book.

Here, as then, they prescribe "more Alberta, less Ottawa," and suggest that, among other things, Alberta should withdraw from the Canada Pension Plan and create its own police force.

Here, as then, they suggest the root of all of Alberta's woes is an indifferent and structurally rapacious federal government — one led, not coincidentally, by a Liberal prime minister.

And here, as then, they season the stew of regional alienation with a mixture of historical facts and contemporary indignities.

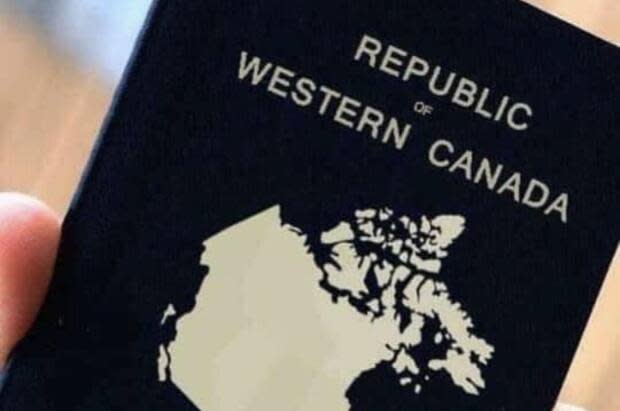

But for all that this new book-length articulation of Alberta's grievances has in common with the letter that spelled them out two decades ago, there is one key difference: it says the quiet part about separation out loud.

"None of us favour separation as a first option," the book's editors write. "But we also see it as a viable last resort if all else fails. It may be that in order to stay in Canada, Alberta must be able and willing to leave it."

This is the political equivalent of trying to bluff someone at poker with an off-suit set of low cards.

Most think separation 'a terrible idea'

Support for separation in Alberta remains muted, even after years of anti-Ottawa priming from politicians like Jason Kenney, now the premier.

In a July poll, only 20 per cent of respondents said they supported separating from the rest of Canada, while 54 per cent said it was "a terrible idea."

And while support for separation is low in Alberta, it's practically non-existent in the rest of the West. People in British Columbia — at least the ones who live on the western side of the Rocky Mountains — have little interest in separating from Canada, and even less in creating some new political entity alongside Alberta and Saskatchewan.

Another obvious problem with the prescription that's been drawn up by Flanagan, Mintz and Morton, and the separatist threat that apparently underwrites it, is that their proposed solutions don't actually solve the province's problems.

Quebec's separatist ambitions may have been flawed, but they presented a clear solution to a shared concern: the protection of their province's cultural and linguistic independence.

But if Alberta was to separate, it would do nothing to increase the price of oil and gas or improve the odds of that happening in the future. It would do nothing to improve its prospects of getting additional pipelines to tidewater — which, after TMX is in service (thanks in no small part to the federal government), may not even be necessary. And it would do nothing to rectify the historical imbalance between the federal taxes that Albertans have paid and the value of the federal programs and services they're received.

Instead, an independent Alberta would be saddled with its portion of the national debt, and forced to fend for itself in a world where its primary asset — the billions of barrels of bitumen in the ground — is worth less with each passing day.

Indeed, it might not even get to claim ownership of them, given the treaties that Indigenous communities signed with the Crown and their potential claim to the land.

And in what would be a remarkable irony, an independent Alberta might soon be in a financial position where it would benefit from a program like equalization — but suddenly be unable to tap it.

Of course, separatism, and the threat of it, isn't really about solving problems. Instead, it's about creating political leverage. And while that worked for the Quebec politicians who have historically deployed it, the same may not be true for Alberta's proto-separatists.

After all, a threat has to be credible in order to be taken seriously, and it has to have meaningful and obvious consequences.

In Quebec, where federal elections are won and lost, that threat was credible — especially after the creation of a federal party dedicated to serving the separatist cause. In Alberta, on the other hand, no such possible threat exists.

What Alberta needs right now isn't a renewed game of brinksmanship with Ottawa, one that will surely damage confidence in the province's future and exacerbate its existing economic and social challenges.

Quebec's success came at a high cost

Quebec's separatist movement may have been a political success, given that it forced Ottawa to bend the knee on any number of occasions and grant it control over everything from immigration to policing. But those political victories came at the cost of massive economic damage to the province, as head offices and small businesses fled in record numbers during its protracted battles with Ottawa.

The last thing that Alberta needs right now is another black economic cloud forming over its head — much less one it effectively chose to create for itself.

Instead, it should be suing for peace.

Kenney is correct in arguing for a more generous distribution of federal funds in his province, and there's an opportunity for Ottawa to call his bluff there. After all, the federal government should invest more heavily in Alberta, both in recognition of its outsized contributions to Confederation in the past and the need to help it adapt and adjust to the economic challenges it will face in the future.

But that can't come in the form of a blank cheque, since Kenney's government has already demonstrated a willingness to put its own name on the payor line.

Instead, Ottawa needs to establish a more direct relationship with Albertans, and help them understand both the benefits of Confederation and the costs that separation would involve.

If they don't, they'll open the door even further for politicians and pundits in Alberta to continue cooking up regional grievances in order to advance their own ambitions — regardless of the cost that voters will ultimately have to pay for eating it.

This column is an opinion. For more information about our commentary section, please read our FAQ.