Opponents say Crown land licence would chop down forest health

Helga Guderley is hoping to notch a hat trick.

Twice, the former Université Laval biology professor has fought to change Natural Resources Department plans since she moved to Boutiliers Point, N.S., and twice she's been successful.

There was the planned cut along the Indian River she and others were able to get reduced in size, as well as one in Ingramport, N.S. But both instances took concerted efforts, she said.

"It's as though the community has to go through all these adrenaline spikes to be able to get DNR to listen to its concerns, and that seems really backward."

Licence applies to western Crown lands

What's in Guderley's sights now, along with others, is a pending licensing agreement between the province and WestFor Management Inc., a consortium of 13 mills, for management of Crown land in western Nova Scotia.

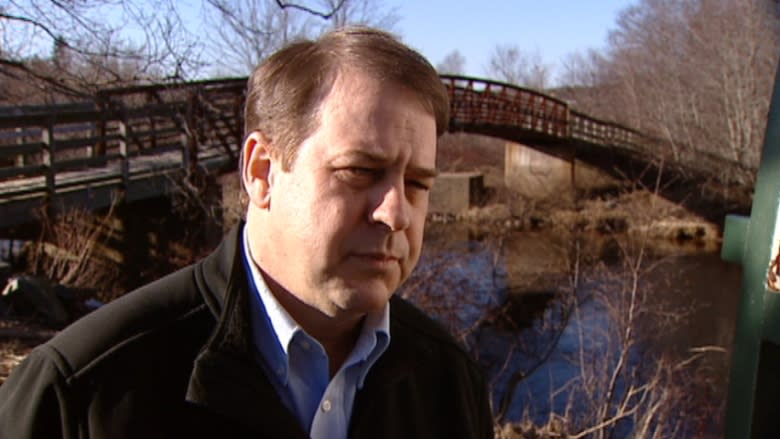

While a deal is not yet in place, Natural Resources Minister Lloyd Hines said talks continue between his department and the group, with eyes on a 10-year licence with a renewal and review option after five years.

"Industry needs to know that they have time to recover their investment and government needs to be diligent about maintaining the rights to influence the operation on the public lands," he said.

Hines sees this kind of a licence, which would be an extension of an existing interim agreement, as a way to ensure professional management on a massive chunk of Crown land the public paid millions to buy.

"What we're looking for is the highest standard of professional management," he said. "By consolidating the access in the WestFor group, then we have the assurance of that professional management."

Guderley and others don't see it that way.

The wrong approach

Clear cutting has gone rampant in the province, she said, and the pending licence with WestFor will only exacerbate the practice. Guderley wants the province to abandon the idea in favour of a process that might lead to the regrowth of traditional mixed Acadian forests.

"I think giving an industrial group 10 years of control over the remaining reasonably forested lands in Nova Scotia is really wrong," she said.

Ray Plourde, the Ecology Action Centre's wilderness co-ordinator, is less diplomatic about the potential WestFor deal.

"[It's] colluding with the mills to give them as much as they possibly can. That's not appropriate, it's not right and it's not what was promised by the government in its official policies."

Hines bristles at the idea the licence is some kind of industrial sellout, highlighting that most of the 13 mills, which buy the majority of private wood in the region, have deep ties to the province.

"We're actually, in this instance, providing that professional management by giving it to a group of people, the vast majority of which is in the hands of Nova Scotia family-owned businesses."

Management is informed by science and what's best for soil and ecology, said Hines.

Consider alternative approaches

Plourde and Guderley don't see how that's possible.

They point to the government's abandonment of its own natural resources strategy and promise to reduce clear cutting by 50 per cent.

True selection management, efforts to develop a strong hardwood industry and other high-value options such as maple syrup production would all be more palatable — the latter having the added bonus of not claiming timber, said Plourde.

"It produces local jobs and you don't have to trash the forests to create the product. But that runs against DNR's sacred tenets of keeping the volume of cutting high and the value, the cost of the wood low for the existing mills."

A rigorous process

WestFor's general manager, Marcus Zwicker, said the licence would help develop long-term management plans for the land and also achieve third-party certification. Decisions are thoroughly scrutinized, he said.

"It's a very intensive process we go through to determine which type of forest management activity we take where."