As overdose deaths spike, families ask why B.C. has failed to fully regulate addiction treatment

Gemma Higgins was 19 years old when she overdosed inside her locked room at a B.C. addiction treatment facility in 2017. She died alone and wasn't found for 12 hours.

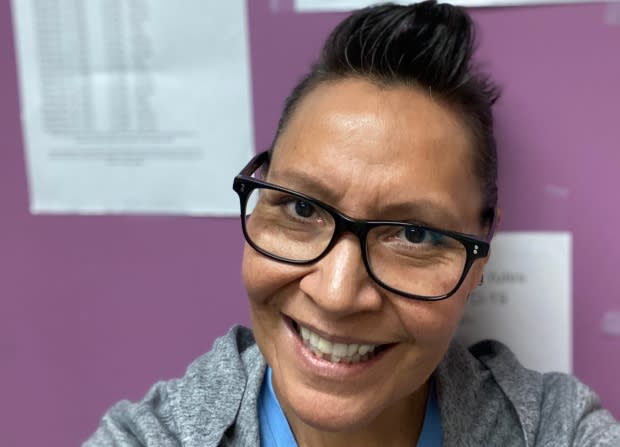

Her mom, Karma LeRoux, says mostly volunteers were working at the facility that night, and none of them checked Gemma's bags for drugs. The centre followed a 12-step approach to addiction treatment and prioritized abstinence over harm reduction, which LeRoux believes contributed to her daughter's death.

"I'm sure she felt shame and stigma and could not tell anyone that she needed to use," LeRoux told CBC.

In B.C., there's no overarching set of rules governing the kinds of treatments offered in these facilities and no provincial system for monitoring them to ensure they're following the rules.

Two years ago, a B.C. Coroners Service death review panel said provincial regulation to ensure evidence-based care at all public and private treatment and recovery facilities needs to be a priority. The panel said this system should be developed by September 2019.

It's now September 2020. More people are dying of overdoses than ever before, but the system of regulation envisioned by the death review panel still does not exist.

"It makes me so angry, because it's not just me," LeRoux said. "I meet other mothers and they have similar stories. No one should be dying in a treatment centre."

Province says it's made 'extremely significant progress'

With the B.C. government's recent commitment of $52 million for new adult and youth treatment and recovery beds, experts and those who've been through the treatment system say now is the time to make sure these facilities are held to consistent standards.

Right now, oversight of addiction treatment facilities is split between the province and regional health authorities. The B.C. government oversees assisted living recovery homes where residents need more support in their daily lives, while the health authorities oversee treatment provided in community care facilities, which require licences if they serve three or more patients.

The Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions argues it has made progress on regulation, introducing amendments to the Community Care and Assisted Living Act that improve oversight of assisted living facilities.

The amendments, which have been in effect since December, require employees to have at least 20 hours of training in a relevant field, give the province expanded powers to inspect facilities and take immediate action on complaints if there is a pressing health or safety risk, and require facilities to provide upfront information about the services they offer.

"These new regulations are an extremely significant step forward to protect people and improve oversight and the quality of care," a ministry spokesperson wrote in an email.

Michael Egilson, chair of the 2018 death review panel, acknowledges that some work has been done to develop standards for recovery homes.

"But that's really not the full intent of that recommendation. It really was looking at the need to provincially regulate and oversee treatment and recovery programs for facilities to ensure evidence-based quality care, and that outcomes are closely monitored and evaluated," he said.

"I don't think anybody would disagree that there's still work to be done there."

He acknowledges that regulation is a "really big undertaking," but says it's crucial for addiction treatment to be dealt with in the same way as programs targeting any other chronic disease.

Egilson said the province has done well at addressing the other recommendations from the death review panel, which focus on emergency responses like making Naloxone and drug-checking services more widely available, but that's not enough to stem the tide of overdose deaths.

"You need both pieces," Egilson said.

'Setting them up for a fatal overdose'

For those who've lost loved ones to overdose or spent time in treatment facilities, a major priority for any regulation system would be offering a range of different treatment options and making sure no one is forced into any options that aren't working for them.

When CBC called every treatment facility in the province in 2016, the majority strictly adhered to the 12-step philosophy of Alcoholics Anonymous, with no alternative options.

Leslie McBain, co-founder of Moms Stop the Harm, said little has changed since then.

"It is a simple and slightly simplistic way of treating people," she said.

While McBain says there's no doubt the 12 steps work for some people, it's not effective for many.

"Every single person who is addicted to a substance and wants to have treatment, wants to recover; their path is as individual as they are," she said.

Byron Wood, a former nurse who has spent time in addiction treatment, says he's most concerned about facilities that don't allow patients to use opioid agonists like methadone, suboxone or hydromorphone to prevent withdrawal.

He also wants regulation to prevent facilities from kicking people out if they fail a drug test.

"That's what's happening at virtually all facilities in B.C. That's not helping people and it's setting them up for a fatal overdose," Wood said.

Ensuring Indigenous patients have access to appropriate care

Advocates say a crucial element for any regulatory system needs to be ensuring that treatment services work for Indigenous people, who are dying of overdoses at a rate five times that of other B.C. residents.

Tracey Draper, program coordinator for the Western Aboriginal Harm Reduction Society, said culture is absolutely key for the people she works with.

"The one thing that we fear a lot, and I can say this from personal experience, is that really, really clinical setting," she said.

"The ideal centre would have an elder presence, would have cultural teachings involved, and wouldn't only be abstinence based."

While patients and families wait for full regulation, Moms Stop the Harm is planning to develop an online pamphlet that explains to families what questions they need to ask of any treatment centre before spending what could amount to tens of thousands of dollars.

McBain is well aware this pamphlet wouldn't be necessary if B.C. followed through on the death review panel's recommendations.

"This wouldn't be the first time that we have done what I consider the province's work," she said.