Boy, 5, overdosed on meds 14 times stronger than prescribed — and regulator didn't punish pharmacy for error

The physical effects of Eli Wilson's clonidine overdose lasted for more than a day. A full 16 hours after taking the medication, video taken by his parents shows the five-year-old falling asleep while standing.

Eli, who has autism, recovered after a night in hospital, but it would take months and thousands of dollars for mom and dad Lindsay and Brent to confirm what they had suspected.

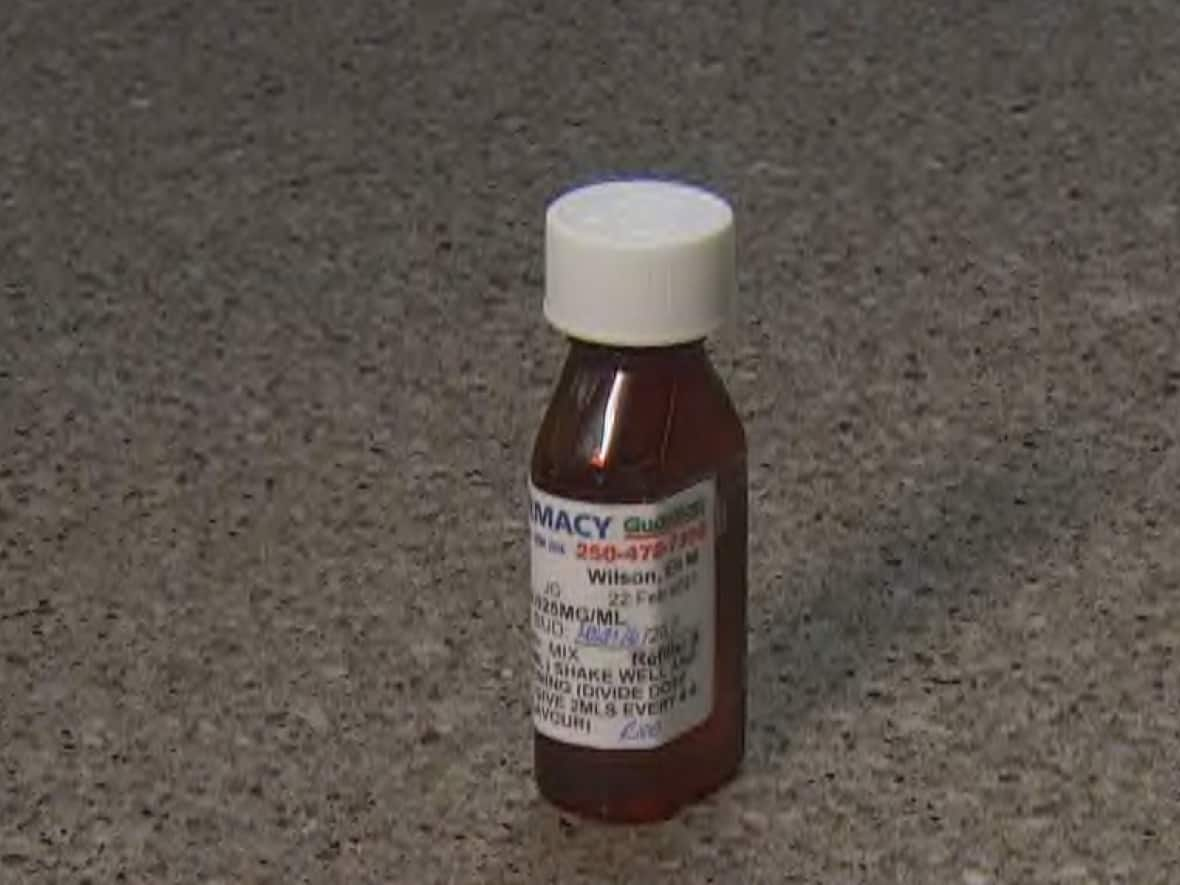

Someone at the Goldstream Forbes Pharmacy in Victoria had made a mistake while compounding the sleeping medication in February 2021.

Eli's clonidine was more than 14 times stronger than his prescribed dose, a lab report shared with CBC shows.

"I burst into tears," Lindsay Wilson remembers.

Her husband recalls their pediatrician saying they'd dodged a bullet.

"As bad as it was, it could have been much, much worse," Brent Wilson said.

Hoping for accountability, the Wilsons filed a complaint with the College of Pharmacists of B.C.

In a letter from the college's inquiry committee later that year, they learned the pharmacy didn't have any standard policies or procedures for compounding medications, and the dispensing pharmacist didn't perform an accurate final check of the drug.

The pharmacists signed consent agreements assenting to remedial actions, but the inquiry committee decided there would be no punitive measures, and nothing about what happened was made public.

"It's completely swept under the rug," Lindsay Wilson said. "If a new customer … is going to do their due diligence, there's no record of this anywhere."

When the college's decision was upheld as "justifiable and reasonable" by the Health Professions Review Board last week, the Wilsons decided it was time to speak out. They believe the college has failed in its responsibility to protect the public.

"I think it's important that people are aware, so they can ask questions of their pharmacists and then make good decisions for themselves," Brent Wilson said.

'No evidence to suggest ill intent'

Pharmacists Ennreet Aujla, who was the manager for Goldstream Forbes at the time, and Quin Andrew, who'd prepared the medication, were both named in the complaint.

Lawyer Elyse Sunshine represented the pharmacists throughout the complaint process, and she told CBC that her clients were restricted from speaking about specific cases because of patient confidentiality.

"Product safety and handling procedures are of utmost importance and staff training around safe and accurate dispensing is in place across all our pharmacies," Sunshine said in an email.

The college has not responded to requests for comment.

In the letter to the Wilsons, the inquiry committee says it decided against punitive measures because "the mitigating factors appeared to suggest that there was no pattern of concerning conduct or unethical behaviour, and no evidence to suggest ill intent."

Under B.C.'s current Health Professions Act, complaints that are resolved through consent, like this one, can only be made public if they're deemed to be "serious matters." The government has promised that will change with the new Health Professions and Occupations Act, which has yet to be enacted.

WATCH | 5-year-old struggles to stay awake 16 hours after overdose:

Eli Wilson has autism, a seizure disorder and sleep disturbances. He takes clonidine every night because sleep deprivation can make his seizures worse, and because he can't swallow tablets, it's necessary to compound it into a liquid, his parents say.

Eli unknowingly took the overdose on the night of Feb. 27, 2021.

The next morning, when the habitual early riser wasn't out of bed by 8 a.m., his parents feared something was wrong.

"It was more than just a deep sleep. We tried to rouse him and we couldn't," Lindsay Wilson said.

Eli's heart rate was 55 beats per minute, much slower than his normal resting rate of 90. His parents watched him pass out over the bathroom sink and standing in front of the open refrigerator.

Eli doesn't speak, so he couldn't communicate what was wrong, and his parents wondered if he'd had a seizure. They spent much of the day talking to their pediatrician about what to do, and say she suspected a clonidine overdose early on.

While his wife took Eli to the emergency room, Brent Wilson says he called the pharmacy to alert them and ask for the clonidine to be tested. Staff called three labs before telling the Wilsons they couldn't find anyone to test the medication, college records show.

The Wilsons ended up paying $5,250 out of pocket for a lab they located on their own, plus the cost of flying it to Vancouver in a helicopter so that it could remain refrigerated.

'It's shaken our confidence'

When the Wilsons filed their complaint, they'd hoped to see something like a recent decision from New Brunswick, where a pharmacist was publicly reprimanded, fined and suspended for a clonidine compounding error that had seen a child given gummies concentrated at 1,000 times the prescribed dose.

"Our B.C. college was not even in the ballpark," Brent Wilson said.

Instead, the pharmacists agreed to hire an outside expert to help produce policies and procedures, complete coursework on preventing medication errors, hold an education session with pharmacy staff and write an essay about what went wrong.

The Health Professions Review Board largely agreed with that resolution, although it said the college should have disclosed to the Wilsons that Aulja was a member of the college's inquiry committee at the time of the complaint. However, she recused herself from all committee panels while the matter was being decided, which the board found to be enough to prevent a conflict of interest.

Eli's overdose has had lasting effects on his family. His parents say he was afraid to go into his bedroom for more than a month afterward, and his twin sister insisted on sleeping next to him for the next year.

"It's shaken our confidence greatly," Brent Wilson said. "Every time we open a new prescription, we're nervous."

They've now switched pharmacies, and start with a tiny dose every time they start a new bottle of clonidine.

"Every time we do that, we hold our breath a little bit," he said.