Pink Floyd's burning man: Aubrey Powell's best photograph

Storm Thorgerson and I had created most of the artwork for Pink Floyd’s albums, including Dark Side of the Moon. One day we were asked to Abbey Road Studios to listen to tracks from the band’s new record. The lyrics were mostly about absence, and the album’s title, Wish You Were Here, was a reference to Syd Barrett, who had left the band some years earlier due to issues with LSD. They were also making a statement about record company executives who regarded musicians as money-making machines, demanding one hit song after another – an absence of a different kind.

We were talking late one night with our friend George Hardie, kicking around ideas. Storm said: “Have a Cigar [the album’s third track], is about insincerity in the music business. What about an image of two businessmen, and one of them is getting burned in a deal?” We all thought the image was a good idea, and I remember saying to Storm: “How are we going to do that?” He replied: “Set a man on fire.”

I went to Los Angeles to find a Hollywood stuntman. The photograph was taken on the Warner Bros back lot in Burbank with Ronnie Rondell, the guy on fire, shaking hands with another stuntman, Danny Rogers. I explained to Ronnie what I needed and he said: “It’s dangerous for a man to stand still on fire. Normally, you’re running and the fire’s spreading behind you, or you’re falling and the fire is above you, or you can always make out with camera angles that the stunt person is closer to the fire than they really are, but to stand still …?” He was very reluctant, but eventually agreed.

I gave Ronnie a suit and wig soaked in flame retardant. Then he was covered in a gel like napalm and set him on fire

I had a suit and wig made that were soaked in flame retardant, Ronnie was covered in this gel – it was like napalm – and his team set him on fire. We repeated the process 14 times, took the shot, and then on the 15th a gust of wind blew up and wrapped the fire around his face and burnt him. He threw himself to the ground and his whole team piled on blankets to put him out. He said: “That’s it! I’m done!” However, I had captured the shot successfully on that last take. Ronnie was very gracious about it considering he had lost an eyebrow and some of his moustache, but as far as he was concerned as a professional in the movie industry it was all in a day’s work.

I knew I had got a special picture. It took a long time to persuade Ronnie to stand exactly as I wanted but in the end he was very brave and it was a perfect composition. Years afterwards Ronnie said his only regret was most people know him more for the Pink Floyd album cover than the famous fire stunts he had performed in movies such as The Towering Inferno.

Back in London, Storm suggested to the band that we should not give away the front cover picture quite so easily and if the album is really about absence we should make the cover photograph absent too. So we shrink-wrapped the whole package in black plastic. When it was released people had no idea what the album cover looked like. Some would tear off the plastic wrapping and throw it away, while others would carefully cut it open with a surgical knife, extract the vinyl and keep the package intact. It felt like Christmas – you are given something, you rip off the paper, which is physical and tactile, and when you open it up there’s a present inside.

Album covers were important in those days. They were signposts to what the band was all about, because you didn’t have MTV, or Spotify or YouTube, and only four or five music papers and maybe a couple of weekly TV pop shows were available to fans.

With Pink Floyd, I always seem to get into some scrape or other. At Roger Waters’ request I flew a giant inflatable pig over Battersea power station for Pink Floyd’s Animals cover, but it escaped into the flightpath of planes flying into Heathrow airport. It could have caused an aviation disaster – thank God it didn’t. We managed to retrieve the pig and rephotograph the shot again the next day, and the photograph looked fabulous in the end.

The image of the band was not a priority for Hipgnosis. What we did care about was creating an eye-catching idea that would be visually and intellectually stimulating but was not necessarily related to the lyrics or the title of the album. We enjoyed creating designs that were visual puns or stories with photographs so when people looked carefully they could decide what the picture was about for themselves. Hipgnosis never gave explanations for our work, and like a mystery novel, a man on fire shaking hands was a conundrum to be solved.

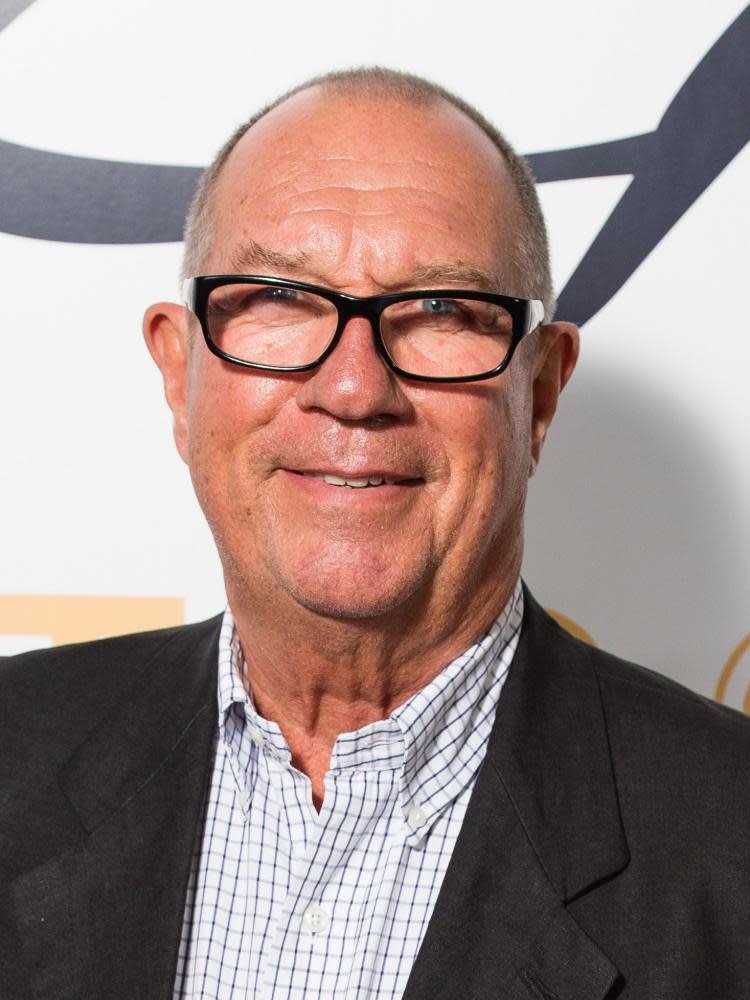

Aubrey Powell’s CV

Born: Worthing, England, 1946.

Training: The London School of Film Technique.

Influences: Salvador Dalí, René Magritte, Luis Buñuel.

High point: “A picture we did very early on for a band called the Nice. It was a picture of 40 red footballs in the Sahara desert.”

Low point: “Doing a photograph that you really think’s going to turn into something great, and it’s a piece of shit. And sometimes there’s no explanation for that.”

Top tip: “You have to network, have acumen, and be street-smart about how you’re going to develop this career and be something.”