Pioneering black hockey players weigh in on Crosby's White House visit

The first all-black line in Canadian university hockey was formed on the fly one October day in 1970.

During a game in Sackville, N.B, Saint Mary's Huskies coach Bob Boucher looked down the bench and signalled to Bob Dawson, Darrell Maxwell and Percy Paris.

Nearly 50 years later, the three players are being recognized in Halifax for their contributions to Canada's favourite game, and they're speaking out about Sidney Crosby's controversial visit to the White House.

The Stanley Cup-winning Pittsburgh Penguins' visit this week has been met with outrage as President Donald Trump criticized athletes in the National Football League for kneeling during the national anthem.

Tampa Bay Lightning's J.T. Brown became the first NHL player to join the protest by raising his fist during the anthem last week.

"We, they, are trying to identify something that is wrong in our society and it's called racism," said Paris. "Isn't it about time we sat down, we talked about this openly and more importantly, let's fix the damn problem."

Racism on and off the ice

To be a black hockey player in the 1970s meant you had to work harder than anyone else on the ice, said Maxwell.

He was used to being the lone African-Nova Scotian member of the team, so when he started playing alongside Dawson, a defenceman, and Paris, a forward, he knew it was something special.

"I thought that was quite unique in itself and then all of a sudden we were on the exact same line and I thought that was even more powerful," said Maxwell, who grew up in Truro, N.S.

But being the first also meant the players battled verbal and physical abuse from the crowd and fellow players. If there was a scuffle in the corner between a white player and black player, Maxwell said you knew who was getting the penalty.

It was rough, but it wasn't anything new, said Dawson, who experienced racism growing up both on and off the ice.

"If you let it get to you, it affects your self-esteem, your ability to play and perform."

Dawson, Maxwell and Paris took part in a panel discussion at Saint Mary's University Thursday called "Hockey and the Black Experience." They'll also join hockey legend Willie O'Ree in a ceremonial puck-drop at centre ice at a Dalhousie-Saint Mary's game Friday night.

Stay focused and work hard

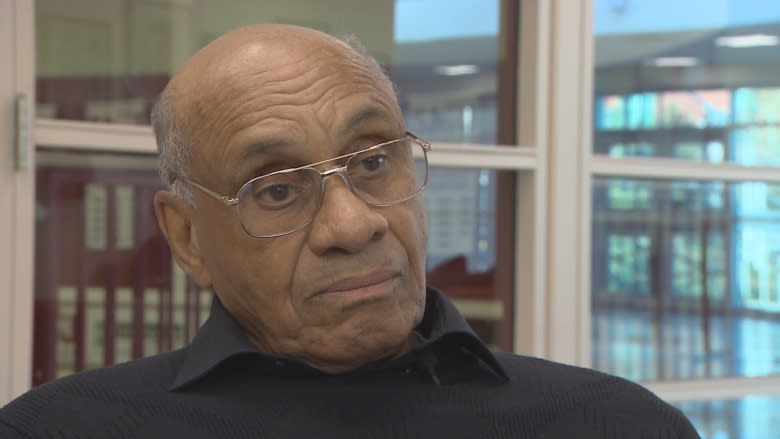

As the first black player in the NHL, O'Ree is all too familiar with the discrimination that comes with breaking down barriers. He joined the league in 1958.

He says it's up to Crosby, and every other player, to do what they feel is right.

"I support protests as long as they're non-violent," said O'Ree.

He credits his brother and mentor for encouraging him to always work hard.

"He told me, 'Willie,' he says, 'If people can't accept you for the individual that you are then just forget about it and stay focused on what you want to do.'"

As the NHL's diversity ambassador, it's a message he passes on to young athletes. There are now about 30 black players in the league, many of whom O'Ree has met over the years.

The Coloured Hockey League

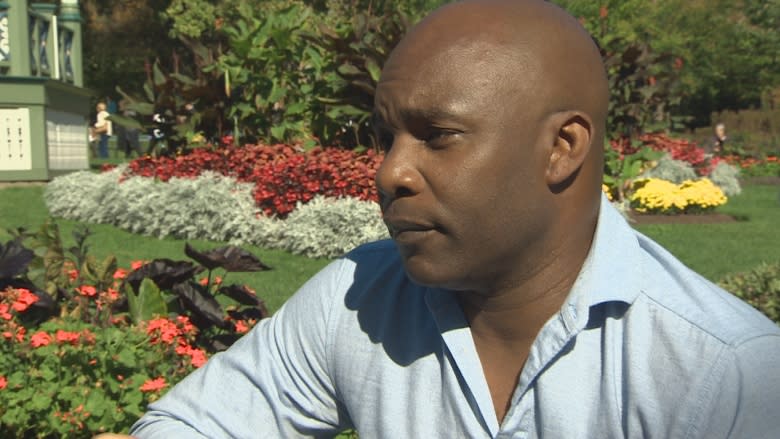

While the number of black players in the NHL continues to grow, recognition has been slow, says documentary filmmaker Kwame Mason.

His film, Soul on Ice: Past, Present and Future, details the contribution of black hockey players, including the history of the little-known Coloured Hockey League.

The all-black league was formed in 1895, and went on to pioneer hockey techniques such as the slapshot and the butterfly goalie position that are still used today.

Mason's film was released two years ago, but he says it's all the more relevant today. He hopes the controversy surrounding the Penguins' decision to visit the White House, and the "take a knee" movement, sparks more than angry words.

He wants a conversation about empathy.

"They don't relate to it," he said of the Penguins. "They can't see the importance of these guys protesting the injustices of blacks in America because it's not a part of their world."