Program allows some Alaska Native Vietnam vets to get land

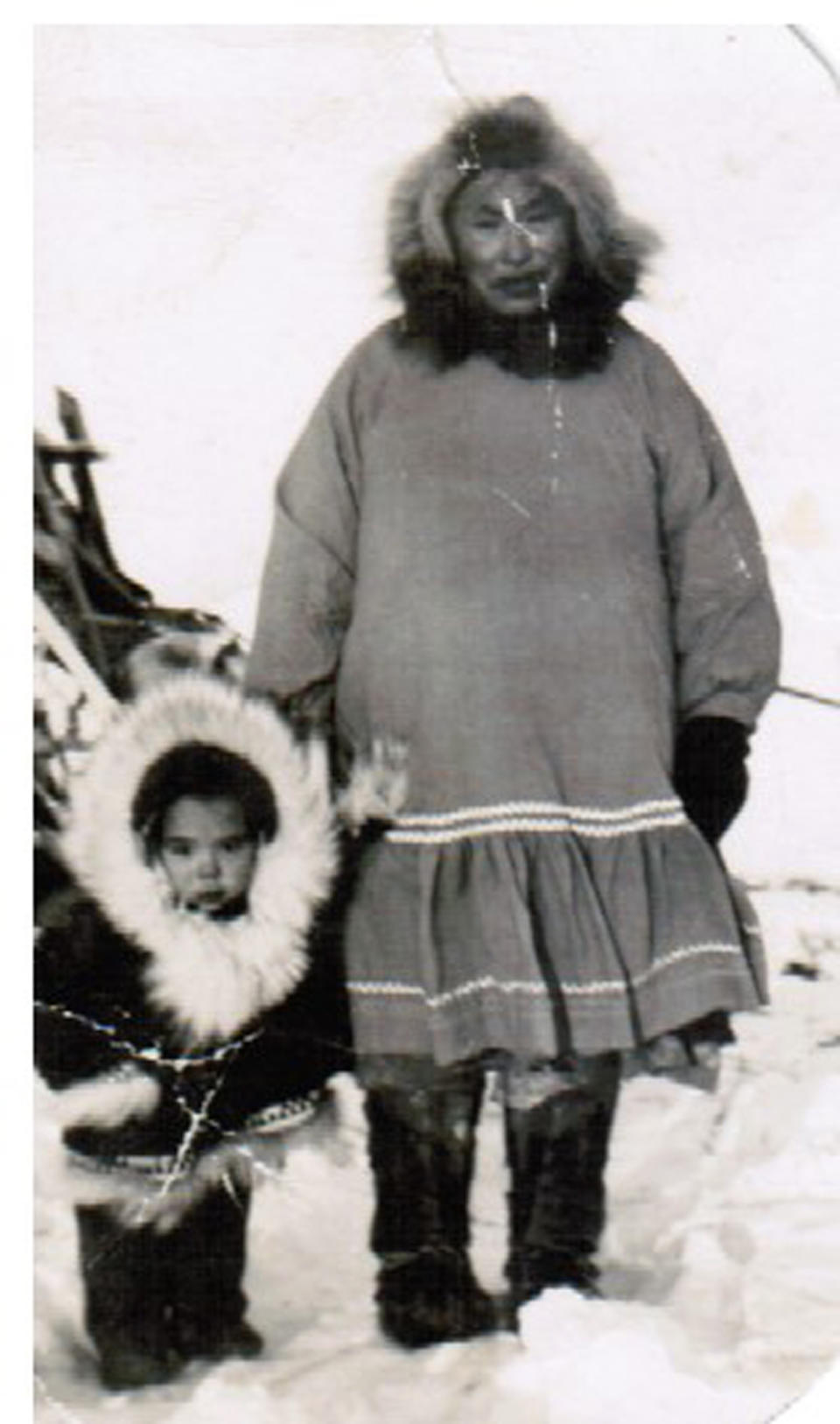

ANCHORAGE, Alaska (AP) — Stewy Carlo had a short life, but he lived every moment. While serving in the Army, he bought a 1951 Mercedes and motored around Europe. After his service years, he roamed South America where he developed a love of photography, and then later turned heads while driving an exotic Maserati to a construction job back home in Alaska.

Carlo, a member of the Koyukon Athabascan tribe, was a math whiz from Fairbanks who quit college in 1967 to volunteer for the Army, to serve in Vietnam. There, he was an aircraft controller who “brought a lot of crippled aircraft in,” said his brother, Wally Carlo of Fairbanks.

Stewy would be an Alaska Native leader today if he had hadn’t been killed in a head-on collision while driving the Maserati in 1975, his brother said.

Wally Carlo intends to honor his brother’s legacy by applying for an allotment of 160 acres (65 hectares) of land in Alaska owned by the federal government.

Alaska Natives were allowed to apply for 160 acres (65 hectares) of land under the 1906 Alaska Native Allotment Act. Before a new law went into effect in 1971, there was a big advertising push to urge Alaska Natives to claim title if they hadn’t already done so.

That coincided with the Vietnam War, when many Alaska Natives fighting the war probably didn’t hear the plea. In 1998, another act allowed the veterans to apply for their land, but both Alaska Natives and Congress felt the window was too short to apply and an occupancy requirement wasn’t fair.

Last year, Congress passed the Dingell Act, expanding the window to apply for land and removing the occupancy provision.

“It’s something that’s really near and dear to our hearts to make sure this program’s a success because we know that folks didn’t have that opportunity,” said Chad Padgett, the Bureau of Land Management’s Alaska director.

The BLM and other federal partners have identified about 1,000 Alaska Native service members or their descendants who might be eligible for the program and is in the process of notifying them. The military and Bureau of Indian Affairs are determining eligibility for another 1,200 people.

There could be more since the BLM estimates 40% of the Alaska Native veterans or their surviving family members have moved out of Alaska and may not know the window will reopen to apply. The BLM also estimates about a third or more of the eligible veterans have died, but their heirs might be eligible.

Veterans or family will have five years to select and apply for land. That window will open sometime this fall.

Currently, there are 1.5 million acres (607,028 hectares) of land available for those allotments, located in three parts of Alaska: the Bering Glacier area near Yakutat, the Fortymile area in Alaska’s interior and near Goodnews Bay in western Alaska.

The land will have restricted titles, meaning veterans can’t sell the land without approval from the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

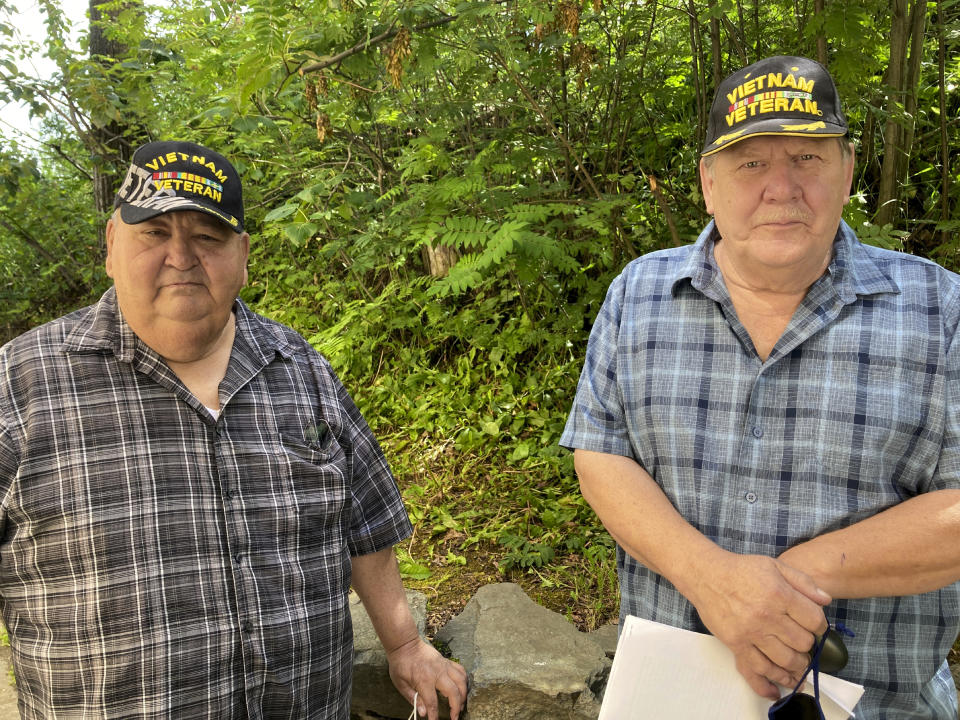

Those locations and the restriction have led to criticism from some combat veterans, including Chris Kiana, who wonders why the government thinks he would like 160 acres (65 hectares) of inaccessible land, between glaciers near Yakutat, land on the complete opposite side of the state from where he was born.

“We’re treated like Third World people in a First World. Pathetic,” Kiana said.

Kiana was born in northwest Alaska in 1943 and calls himself an urban Eskimo since he now lives in Anchorage.

He joined the Navy and served on a ship that saw heavy fighting in Vietnam. He didn’t know Harold Rudolph at the time, but said his ship likely lobbed shells over Rudolph’s Army unit during battles.

Rudolph, who is part Aleut and part Tlingit, was born in Valdez in 1948. He served in an artillery unit with the 25th Infantry Division near Saigon during his two-year tour.

Both say the land being offered is not in their ancestral areas, it’s off the road system and inaccessible — challenges that are not appealing for men of their age.

“We’re trying to make lands available that are desirable and accessible, and access in Alaska is a lot different than what you might think of down in the Lower 48,” Padgett said.

“And unfortunately, most of the BLM lands is in an area where you’re going to have to get there by boat, snowmobiles, snow machine or plane. It’s just that’s the way the land pattern is at this point, but that we’re trying to make some changes to that,” he said.

The BLM is recommending that an additional 15 million acres (6,070,286 million hectares) become eligible for allotments.

Kiana and Rudolph have another solution.

They would rather be paid cash for their allotments, say $3,000 an acre. Then they could use the $480,000 to buy a home elsewhere.

“Why don’t they allow us a buyout so we can go buy a cabin close by, buy a house close by with a few acres? That’s about what we can do with that amount of money,” Kiana said.

Instead, the government is offering land where “we have a helicopter out to in most cases or parachute into. Does that make sense?”

By statute, the government can’t do that, said Padgett “That’s something that they have to take up with Congress.”

Wally Carlo would like to secure land near the Yukon River bridge on the Dalton Highway, the supply road that runs north of Fairbanks to the oil fields on the North Slope. That’s where other members of the Carlo family previously secured their allotments, but that area isn’t currently being offered.

Even if they can’t get that preferred land, Carlo can’t imagine trying to sell it back for cash to the government.

“We believe that it’s not for just our generation now, but for three or four hundred years,” he said. “Hopefully, it’ll stay in the family, and we’ve set up a trust to make that happen.”