How to protest China's human rights violations without boycotting the 2022 Olympics

With one year to go before the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics, there has been talk of boycotting the Games to protest China’s persecution of its Uyghur population — and for the continued detention of two Canadians.

The act of boycotting the Olympics is not as simple as it appears.

Governments don’t send athletes to the Olympics. National Olympic Committees send athletes — and they are supposed to operate independently from their country’s government.

In Canada, the Canadian Olympic Committee is a not-for-profit corporation. If the government of Canada wanted to boycott the Beijing Olympics, it would have to persuade the Canadian Olympic Committee not to send athletes.

Pulling funding for athletes

The government could try moral suasion or it could simply pull funding to coerce the Canadian Olympic Committee to go along. But pulling funding from Olympic athletes, who are already arguably underfunded, may not be a popular decision.

Read more: How the rescheduled Tokyo Olympics could heal a post-coronavirus world

If the government did get involved, the Canadian Olympic Committee and Canadian athletes could face sanctions from the International Olympic Committee. The IOC has banned India’s National Olympic Committee from the Olympics over political interference. And Italy’s National Olympic Committee recently raised concerns about sanctions in response to a new law reducing its power in Italian sport.

Boycotts are historically ineffective

Even if the Canadian Olympic Committee went along with a boycott, it is unlikely to be effective.

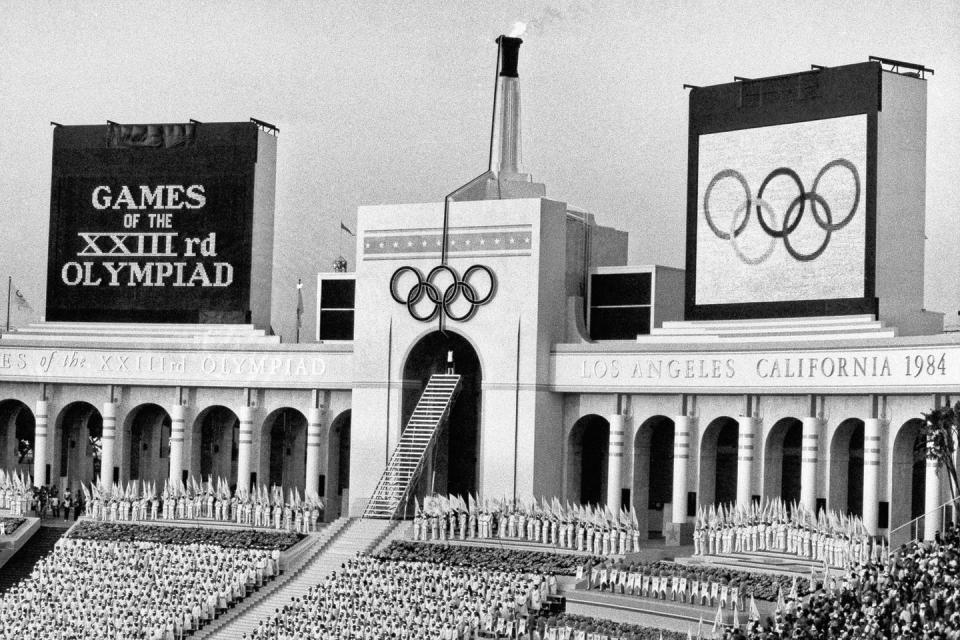

The two most significant boycotts of the Olympic Games — the American-led boycott of the 1980 Moscow Games and the Soviet-bloc boycott of the 1984 Los Angeles Games — failed to achieve their goals.

The 1980 boycott was in response to the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan, but the Soviets remained in Afghanistan until 1989. The 1984 Soviet-led boycott was a response to the 1980 boycott. The 1984 Games, the first to turn a massive profit, saw American athletes winning a record number of medals because of the absence of Soviet and other Communist bloc athletes.

A boycott of Beijing 2022 could look at lot like the 1984 boycott.

Boycott could help Chinese athletes

China wants to become a winter sports power. If the Games were boycotted by Canada and other countries that are traditionally strong winter sports performers, it would open the way for more Chinese athletes to win medals.

More medals won by Chinese athletes would benefit the government of China, rather than punish it for its actions against the Uyghur population or the two imprisoned Canadians.

The focus of the debate over human rights and the Olympics needs to be on the International Olympic Committee. The IOC, which holds the rights to the Games, could put pressure on China. But that’s unlikely.

First, there is no provision in the Host City Contract between the International Olympic Committee and the city of Beijing that would enable the IOC to remove the Games based on human rights issues.

Additionally, the IOC would not want to find a new, last-minute host for the 2022 Winter Games after already delaying the 2020 Summer Olympics in Tokyo by a year due to COVID-19. The IOC is committed to the Games going ahead as planned, seen in the refuting of a recent report suggesting that the Tokyo Games will be cancelled.

Although one might look to the International Ice Hockey Federation’s recent removal of the 2021 World Championships from Belarus as an example for the IOC to follow, it’s a slightly different situation. Formally, the federation pulled hosting rights to protect the safety of players and officials. Informally, it pulled hosting rights because a major sponsor threatened to withdraw funding. Neither of these appear to be the case for Beijing 2022.

Sport diplomacy a better route

Instead, it’s probably more helpful to use participation at the Beijing Games as a way to raise awareness of human rights issues and a form of sport diplomacy.

We have seen this play out with Qatar’s labour law reforms following intense scrutiny as it prepares to host the 2022 FIFA World Cup. Professional sports leagues have also provided an avenue for athletes to raise awareness about Black Lives Matter, an example of positive engagement.

The hurdle to this approach is the Olympic Charter’s Rule 50.2 that states:

“No kind of demonstration or political, religious or racial propaganda is permitted in any Olympic sites, venues or other areas.”

This rule has been criticized and the International Olympic Committee’s Athlete’s Commission is putting forward recommendations to reconsider the rule, including input from Canadian athletes.

This is not to say that raising awareness, demonstrations and protests by athletes will solve the problems. But history shows us that athlete protests can have a powerful effect.

What could affect more change? Having more athletes with the bravery of Tommie Smith, John Carlos and Peter Norman — who used the medal podium at the 1968 Mexico Olympics to protest anti-Black racism — or Canadian athletes staying home next year?

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts. It was written by: Ryan Gauthier, Thompson Rivers University.

Read more:

Ryan Gauthier does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.