Will psychedelics become mainstream? This Calgary company is betting on it

Danny Motyka discovered his love for chemistry when he was high on LSD back in the mid-2000s. The single tab of blotter acid — emblazoned with images of tongues from the rock band Kiss — set him on a path to push psychedelics out of the shadows.

Now 31, Motyka is the CEO of Psygen, a Calgary business hoping to manufacture synthetic psychedelics for the pharmaceutical industry. While the application of hallucinogens in medicine is in its infancy and remains highly speculative, Motyka and his company of believers are encouraged by renewed interest in the field.

"There's a huge market opportunity here," Motyka said.

A spate of early scientific research — along with big injections of cash from wealthy and celebrity investors — has triggered a renaissance of sorts for psychedelics, which for decades were pushed underground by the war on drugs.

Companies want to be the next psychedelic unicorn

Dozens of companies have emerged in recent years, seeking to get in on the ground floor of a fledgling industry they bet will take them higher. Some, like Germany-based Atai Life Sciences and the U.K.'s Compass Pathways, have become unicorns — not some kind of hallucination, but the type of startups worth more than $1 billion.

"We're really breaking ground here in that psychedelic chemistry has been illegal, and now we're able to do it in a legal context," said Peter van der Heyden, Psygen's co-founder and chief science officer.

"It's never been done before."

Potential for a new industry

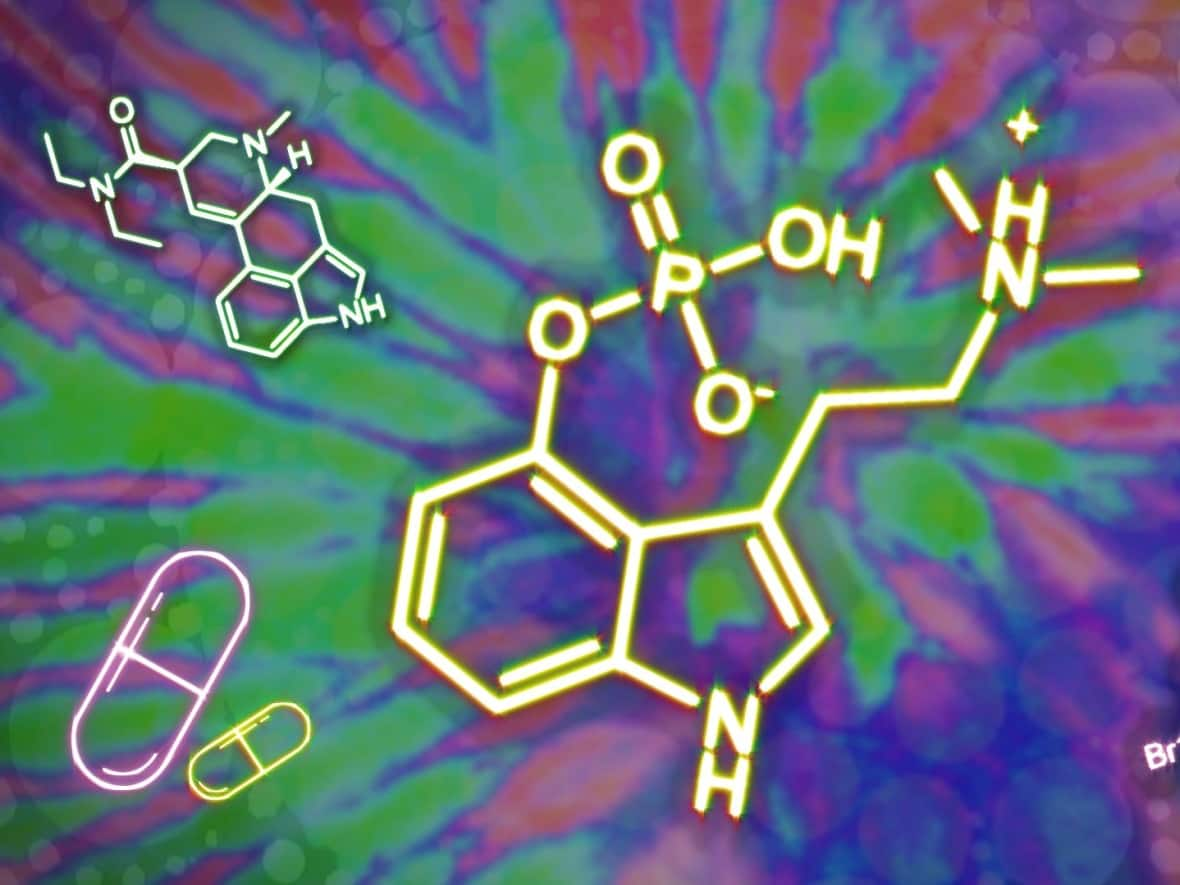

Magic mushrooms, LSD and other psychedelics are hallucinogenic drugs that remain illegal to possess for recreational use. But some regulators such as Health Canada have allowed for research into them as possible treatments for mental health conditions, sending companies and investors on a trip to a new industry.

While the sector initially attracted an early rush of investor enthusiasm, some of the euphoria has already begun to fade as shareholders come to grips with the long and uncertain road ahead.

Researchers are still running clinical trials looking into whether substances like psilocybin, the active ingredient in magic mushrooms, can effectively and safely treat depression, or whether MDMA, often found in ecstasy or molly, can help patients with post-traumatic stress disorder.

"We have to go through the entire drug approval pathway and demonstrate safety and demonstrate efficacy," van der Heyden said. "So it's too early, really, to say we know that these things work."

Production expected early 2022

Psygen's lab, currently under construction, would initially manufacture psychedelics for research and clinical trials, though it still needs Health Canada approval. The company hopes those trials lead to the creation of new therapeutic drugs, allowing its lab to expand to commercial-scale production of medical-grade substances.

They've asked Health Canada for a dealer's license, which gives special permission to handle and produce controlled drugs that are otherwise illegal to possess. The designation comes with a strict set of rules, including security measures to prevent theft, proper record keeping and reporting.

For now, company officials are optimistic the first phase of the project will secure the green light from federal regulators and they can start producing psychedelics by the end of March 2022.

By then, the facility would be capable of producing 12 to 15 kilograms of synthetic psilocybin a year, enough to fill demand from clinical research, Motyka said.

Marijuana paves the way for mushrooms

The Alberta business has applied to handle eight different psychedelic drugs, though its CEO said psilocybin is the substance most in demand from drug development companies, likely because of loosening cannabis laws.

"That's reflective of this liberalization of plant medicines. It's easy to go from cannabis as a medicine to mushrooms as a medicine," Motyka said. "It's a bit harder to make that next jump to LSD, especially with the amount of stigma that's associated."

Researchers are looking at psilocybin's potential to treat various conditions, from anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder, to problematic substance use. Health Canada, which has approved three clinical trials testing the drug in treatment of depression, said psilocybin has so far shown some promise in some cases, but further research is needed.

"Clinical trials are the most appropriate and effective way to advance research with unapproved drugs such as psilocybin," the regulator said in a statement.

"Clinical trials ensure that the best interests of patients are protected and that a product is administered in accordance with national and international ethical, medical and scientific standards."

'Hungry for something new'

Industry observers say the legalization of cannabis for recreational or strictly medical purposes in many parts of the world has helped to ease stigmas and convince investors to pump hundreds of millions of dollars into psychedelics.

Plus, the outbreak of the deadly COVID-19 virus — and the rounds of restrictions that came with it — triggered a fresh wave of mental health concerns. And it's happening at a time when people are interested in unconventional ways of looking at problems, said Leila Rafi, a Toronto lawyer with clients in the industry.

"There's a lot of investors out there who are willing to put a little bit of money into this industry and see what happens — and even take a bit of a hit," said Rafi, a partner in McMillan's capital markets group.

"And I think investors are just hungry for something new."

Psychedelic stocks in a lull

Steve Hawkins, the CEO of financial services company Horizons ETFs, runs a fund that allows people to invest in the broader psychedelics market. The exchange traded fund (ETF) tracks a couple dozen publicly traded companies that are heavily involved in, or have significant exposure to, the industry.

So far, it's individual investors, rather than big pension funds, that have parked money in the fund, Hawkins said.

"This is still a very early stage investment proposition."

An initial burst of investor excitement has given way to a lull in recent months, with share prices for drug development firms plunging. The Horizons psychedelics ETF has lost half of its value on the stock market since hitting a peak in February.

In an industry where companies are not making money, stock prices are driven by other developments, including news of breakthroughs in research. But there haven't been enough intoxicating incentives to lure investors back, Hawkins said, noting that while share prices have fallen from their peaks, they are still above where they were in 2020.

Investors hooked on psychedelic ventures also face plenty of risk.

"All investors who are investing in early stage drug development companies need to be prepared to lose a substantial amount of money - Eric Foster, Dentons lawyer

Firms that are attracting troves of investment dollars are often burning through all that cash researching drugs that may not materialize, Hawkins said. "These are very risky companies."

Some could fail, similar to what happened in the cannabis industry.

"All investors who are investing in early stage drug development companies need to be prepared to lose a substantial amount of money," said Eric Foster, a partner at Dentons law firm who helps investment banks finance psychedelic ventures.

"The (potential) upside is that they will be able to take a candidate all the way through the regulatory approval process, and effectively get to a drug that's been approved … Then, all of a sudden, it's going to be worth significantly more."

A new frontier

The very idea that psychedelics could emerge from the shadows of a decades-long drug war and pave the way to a new frontier of medicine has inspired other investors with deep pockets.

Liam Payne, the British One Direction singer, along with PayPal co-founder and billionaire Peter Thiel are on the growing list of celebrity investors. New York Mets owner Steven Cohen, Shark Tank's Kevin O'Leary and Tim Ferriss, the podcaster and author of The 4-Hour Workweek, are also on the roster.

Then there's Sa'ad Shah. Convinced that researchers are only scratching the surface of psychedelics' potential power to reshape mental healthcare, he co-founded a venture capital player focused on the industry.

Shah has been raising money from friends, various CEOs and ultra-high-networth investors to build a warchest to unleash on dozens of companies. The Noetic Fund, based in Toronto, raised $32 million US in its first round and invested it into 22 ventures, including Calgary's Psygen. Now, it's on the hunt for another $200 million.

Nearly halfway there, Shah said he's not facing the same kind of investor burnout that has sent stock prices tumbling. He said most of the "crown jewels" in the industry remain privately held companies that continue to raise funds.

"It's a burgeoning industry," Shah said. "It's an incredibly exciting industry. It is a bit of the Wild West."

An opportunity and a business venture

Van der Heyden, Psygen's co-founder, says he found a gap in this Wild West landscape when he spoke with researchers who couldn't get their hands on pharmaceutical-grade psychedelics for their studies. He saw an opportunity.

A child of the hippie era of the 1960s and early 1970s, he said the counterculture movement exposed him to drugs like LSD. But it wasn't until his retirement that psychedelics became a possible business venture.

And it's made for some unusual conversations.

"I might be sitting at the barber and he asks me, 'What do you do?' And so I say, 'Hey, guess what? We make psychedelic drugs.'"