Quebec man tortured in Mexican prison wants answers from federal government

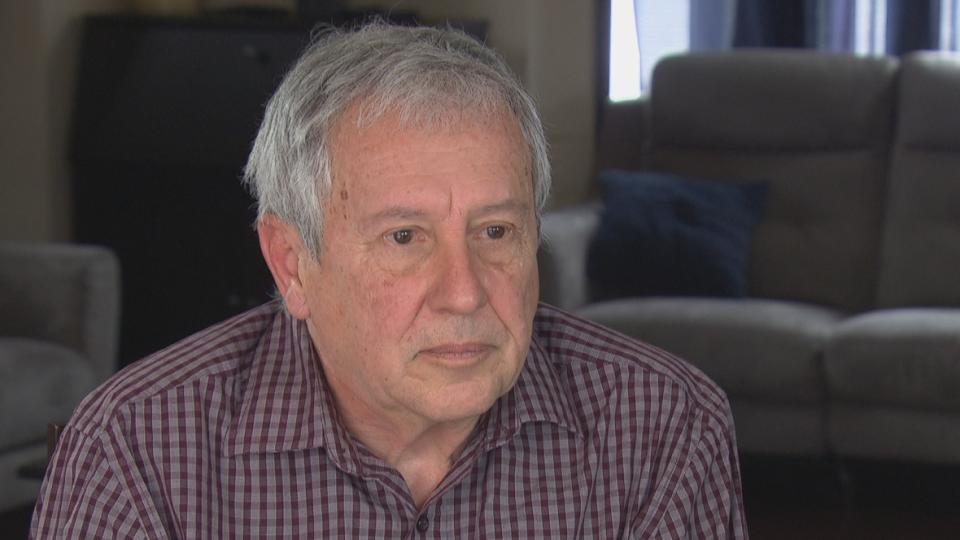

Régent Boily sits in his kitchen at his home near Montreal, where he has been living since he was released from a Mexican prison. Daylight streams in from a large window.

This is "his favourite spot," after spending more than 10 years locked away.

That incarceration left its mark on the 74-year-old. Though still quick-witted, his gestures are marked by nervousness.

"If I go to a restaurant, I have to sit with my back against the wall, because I have to see who's around me. I'm afraid of being assaulted," the ex-convict said, his hands clenched.

"I have nightmares where I drown or there are rats eating me from the inside."

Those nightmares have shaken Boily from his sleep ever since he was first tortured in a Mexican prison on Aug. 17, 2007. He described how guards dunked his head under water about 10 times in a row.

"The barrel was full of water. There was a bag of potato chips and a dead rat floating on the surface, and I could see little bugs swimming around," Boily said.

"I could feel things coming into my mouth. It was the worst moment of anxiety that a human being can experience. Each time I went under, I was sure I was going to die … I was spitting, vomiting. They kept dunking my head back into my vomit."

A troubled past

Boily, originally from Hull, Que., accepts that he has made mistakes in his life. Grave mistakes.

The first was in 1998. At the time, he was living in Mexico and had agreed to transport some 580 kilograms (about 1,300 pounds) of marijuana in his motorhome.

Boily was caught, arrested, convicted of drug trafficking, sentenced to 14 years and thrown in jail. He escaped in 1999: while he was on an escorted trip outside the prison for an eye exam, accomplices freed him from a car.

During the escape, a prison guard was killed. Boily says he only learned of the guard's death later from the TV news.

Boily fled to the Outaouais region of Quebec, where he lived uneventfully for six years.

In 2005, justice caught up with him. He was arrested at his home in La Pêche, Que., north of Gatineau. Nicknamed the "fugitive of La Pêche," Boily was wanted by Mexican authorities who called for his extradition.

At the time, Boily was ready to serve a sentence for the crimes, but feared returning to Mexico, where he was tortured by police after his initial arrest in 1998.

From 2005 to 2007, he remained in custody at the Hull prison, while his lawyers, Michel Swanston and Christian Deslauriers, exhausted all possible avenues to prevent his extradition to Mexico.

"Back then, we went on Yahoo — a search engine — we typed 'torture' and 'Mexico,' and there were over a million hits that came back," Deslauriers told Radio-Canada in an interview.

Broken promises

Canadian and international law prohibits Canada from deporting anyone to a country where there is a serious risk they may be tortured.

But in 2007, the Harper government convinced Canadian courts that this risk had been ruled out in Boily's case. Rob Nicholson, who was then justice minister, obtained diplomatic assurances from the Mexican government that it would respect Boily's rights.

An eight-page document lists the guarantees provided by the Mexican constitution.

The Harper government promised that a monitoring mechanism would be put in place by the Canadian Embassy in Mexico to ensure that Boily's rights were respected once he was back on Mexican soil.

"All of that was just smoke and mirrors," Swanston said in an interview with Radio-Canada. "Through an access to information request, we learned that no monitoring whatsoever was ever put in place."

Emails from Canadian officials at the time show that Boily's extradition took them by surprise.

On Wednesday, Aug. 15, 2007, officials with the Department of Foreign Affairs in Ottawa and the Canadian Embassy in Mexico circulated a newspaper article.

"I see from the media that it may be imminent that Mr. Boily will be extradited back to Mexico," an email said. It also said officials didn't even have a copy of the diplomatic assurances made by Mexico.

Another surprise came the following day — Thursday, Aug. 16, 2007 — when embassy staff learned that Boily would be extradited to the Zacatecas prison, the same one from which he had escaped.

"I am concerned … that reprisals are possible … considering that a guard was killed during that escape," a Canadian bureaucrat in Mexico wrote. She notes that even "in Canada, we would avoid placing an inmate in that kind of situation."

According to another message, the Consul General of Canada in Mexico, Robin Dubeau, tried to reach Mexican authorities to ask for Boily be sent to another prison.

But his efforts were quickly halted by the Department of Foreign Affairs in Ottawa.

One internal document dated Aug. 16, 2007, reads: "Following internal consultations, we suggest that we not intervene at this time, given the guarantees provided by Mexican authorities and accepted by the Canadian government."

Torture sessions

On Friday, Aug. 17, 2007, Boily was extradited to a prison in Zacatecas, a state of Mexico.

That same night, Boily said, guards brought him to a deserted corner of the prison and he was tortured.

"I looked at the water and said, 'No, not that.' I fought back," he recalls. That's when guards forcefully plunged his head into the barrel. "The need to breathe out, not being able to breathe causes intolerable pain."

Boily said he was also choked using a plastic bag.

"The plastic bag, that's to make you lose consciousness. I was afraid of dying, but there were times where I wish I had died," he said. "It's hard to know that you'll lose consciousness. They squeeze a plastic bag around your neck. You can see the condensation from your breath. At some point, you can't see anything."

He regained consciousness when his head was again plunged into the filthy water.

These suffocations with water and the plastic bag left their mark, Boily said.

"After choking like that, I had problems with my balance. I had memory problems. I even have moments of absentmindedness were I lose all contact with reality," he said.

These abuses were repeated during his first days in prison.

Boily was also beaten, violently pushed around from one guard to another. They also injected hot sauce up his nose.

"My mouth was swollen. I could only eat liquid meals and drinks, until things cleared up," he recalls.

"I was quietly told that I had to suffer for the death of the guard who was killed during my escape in 1999," Boily said. "I deserved time in prison for what I did. I admit it. That's not a problem. But why torture someone?"

Just as Boily was returned to prison in Mexico, former Canadian prime minister Stephen Harper was hosting the presidents of Mexico and the United States for a summit in Montebello, Que., on Aug. 20 and 21, 2007.

"We sacrificed him for the sake of our international relations with Mexico. That's how I interpret the government's actions," said Swanston, one of Boily's lawyers.

Staff at the Canadian Embassy in Mexico only visited Boily on Aug. 22, 2007, five days after he was first imprisoned.

A report of that meeting, prepared at the time by the embassy, described the same torture and mistreatment that Boily described. According to that same report, embassy staff met with the prison director on the same day to express their concerns about the safety of a Canadian citizen.

Boily's mistreatment at the hands of his guards came to an end after that visit.

Dubeau, who was Canada's consul general to Mexico when Boily was extradited in 2007, confirmed five years later in court that despite the Harper government's commitments, no specific mechanism was put in place to monitor Boily's case.

He also said that at the time of Boily's arrival in Mexico, embassy staff has not received a copy of the diplomatic assurances provided by the Mexican government.

Boily said the terror of his first nights back in the prison will never leave him.

"At night, I was sitting in my bed, looking at the hallway thinking, 'Maybe they'll come. Maybe they won't. Oh my God — they're opening the doors. Are they coming for me?' I was delirious."

After years of repeated nightmares and poor detention conditions, Boily tried to put an end to it all one night in his cell.

"One night, I said, 'It's time to stop this.' There was a big window with bars about every six inches — square bars. So, I tied my bedsheet to it …"

His voice trails off.

"I don't want to say it. It's too hard. I'm sorry."

Radio-Canada contacted the former Conservative ministers who were responsible for Boily's case in 2007, former justice minister Rob Nicholson and former foreign affairs Minister Peter MacKay. We asked them to respond to Boily's accusations that they failed in their duty to protect him. They did not respond to emails.

Decision unheeded

The Trudeau government repatriated Boily in June 2017 so he could serve the rest of his sentence in Canada. He was transferred to the Regional Reception Centre, a maximum-security institution in Sainte-Anne-des-Plaines, Que. He was released on parole on Dec. 12, 2017.

Boily's lawyers have since made repeated requests that the federal government implement a decision by the United Nations Committee Against Torture.

In 2011, the committee ruled that the Canadian government at the time had violated the United Nations Convention against Torture by extraditing Boily to Mexico.

The committee concluded that the Canadian government should:

- Compensate Boily for the torture he endured.

- Offer him as full a rehabilitation as possible through medical care and legal services.

- Review its system of diplomatic assurances to avoid similar violations.

"Mr. Boily is a broken man," Swanston said. "He suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder. He needs help. Compensate him for the torture he endured, give him the care he's owed, and respect the tribunal's ruling."

Radio-Canada asked the Trudeau government whether it will implement this decision.

In an email, a spokesperson for the Department of Justice said "the government of Canada takes its obligations under international law seriously."

The spokesperson also noted that Boily had sought remedy from the Federal Court of Canada.

"At this point, the government has no plans to compensate Mr. Boily," he wrote.

Boily is suing the Canadian government for $6 million in damages and interest. But he has already indicated to the Trudeau government that he is willing to settle his case.

Another Canadian detained abroad

"When a Canadian government willfully turns its back on defending a Canadian's rights and allows a Canadian to be tortured and mistreated, we all end up paying." That's how Trudeau explained in recent months his decision to compensate another Canadian who had been imprisoned abroad: Omar Khadr.

Some in Canada consider Khadr to be a victim. Others see him as a terrorist.

"The Charter of Rights and Freedoms protects all Canadians, every one of us, even when it is uncomfortable. This is not about the details or merits of the Khadr case," the prime minister said on another occasion.

Boily's lawyer, Christian Deslauriers, says he worries that Canada hasn't learned any lessons from his client's extradition.

"I have no information indicating that this procedure has changed," he said. "In Canada, it's a crime to torture an animal. If we tie up an animal, don't take care of it, beat it, we can face criminal charges. And we're sending a human being into those kinds of conditions."

Today, despite his health problems, Boily has found another reason to live.

"My grandchildren, I didn't know them. They came to see me right away. I needed that," he said. "My grandchildren — I love them more than anything."

His new role as a grandfather gives him motivation to continue his fight against the Canadian government.

"I want them to recognize the error they made. I don't want this to happen to someone else, to another Canadian."