Queen of Soul Aretha Franklin remembered in her hometown as a 'regular Detroiter'

Tributes are pouring in for Aretha Franklin who passed away Thursday morning of advanced pancreatic cancer in her Detroit home. She was 76.

Fans paid their respects to the Queen of Soul in front of the city's New Bethel Baptist Church — where her father, C. L. Franklin, was once a pastor.

Many are remembering her not just for her presence and energy on stage, but for her ability to blend in with the fabric of Detroit.

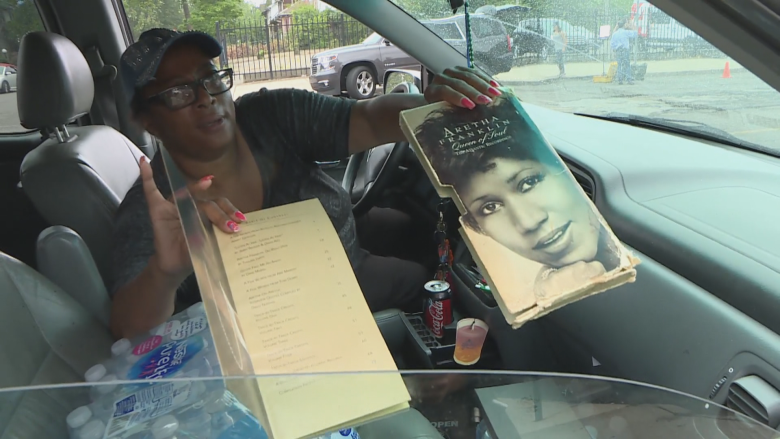

Lythe Aikens, 54, first started hearing Franklin's music when she four years old. She said music from the 20-time Grammy Award winner would constantly be playing in her home.

"I feel an empty space inside," she told CBC News. "I was playing her music the other day and I was just crying [because] she was sick. When she passed away this morning, I just got up, took a shower and walked down here in the rain."

Aikens moved to Detroit from Houston, Texas in 2013. She said as popular as Franklin's music is in Detroit, it was just as well-received in her former city.

"When I moved [to Detroit], I was like, 'Where'd you get that music?' People said, 'She's from here! You don't know of Aretha Franklin? She's from here!' I'm like, 'We love Aretha Franklin in Texas.'"

Crossed generations

Anthony Bailey lives across the street from the church and said, while he was surprised to hear of her death, he considers this time of remembrance as a "celebration."

"She lived her life… She was definitely an icon," Bailey said.

"I'm a young cat and everybody still in my generation is listening to her. [She has] a huge legacy. That's why it's a celebration."

Robert Smith Jr., the senior pastor at New Bethel Baptist, took the position in 1982 after C.L. Franklin's retirement three years prior.

Smith Jr. said her nickname tied well with his memories of the singer's personality off the stage.

"She was a queen. She expected to be treated like a queen," he said, adding she inspired people to chase their dreams in a city "known for murder, crime and poverty."

"She was a Detroiter all the time."

Many members of the congregation were distracted by having one of the most famous singers in the world in the pews, he said. But they always "kept their cool" around Franklin because of the people she kept around her.

"I wouldn't call them security guards. But if they had a hand up to stay back, you stayed back."

Across the border in Windsor, Ont., Caesars Windsor entertainment director Tim Trombley remembers meeting Franklin in person. Trombley's mother, Rosalie Trombley, was the music director for the local radio station CKLW.

"The radio station played all of her hits. My mother was able to meet her on several occasions. I was able to see her perform as a young man on several occasions," he said.

Franklin performed at Caesars Windsor in February 2016. Trombley recalls that night as one of the most "magical" in the casino's ten-year history.

"She walked out on that stage in that mink coat. It was just her presence on that stage… It was just two hours of magic," he said.

Philanthropic figure

Elise Harding-Davis, an African-Canadian heritage consultant and historian, has early connections to the Franklin family. She said C.L. Franklin married her parents back in the 1940s before her father left for the second World War.

She remembers the iconic singer as a beautiful, young woman who was a "consummate entertainer."

"She told life through stories in her singing. She had a four-octave range which is extremely unusual. Really a gifted singer," Harding-Davis said, adding her philanthropic ventures were often overlooked.

"During Hurricane Katrina, she housed people, gave them places to live, fed them, gave them clothes — all paid for out of her own pocket."

Fame never went to Franklin's head, according to Harding-Davis, who said when her daughter worked at a local supermarket, she would often hear stories of the music superstar's frequent visits.

"Miss Franklin would come in just like any other person. She was a regular Detroiter," she said.

"She'd line up, buy her food like everybody else and go about her business."

With files from the CBC's Colin Côté-Paulette and Dale Molnar