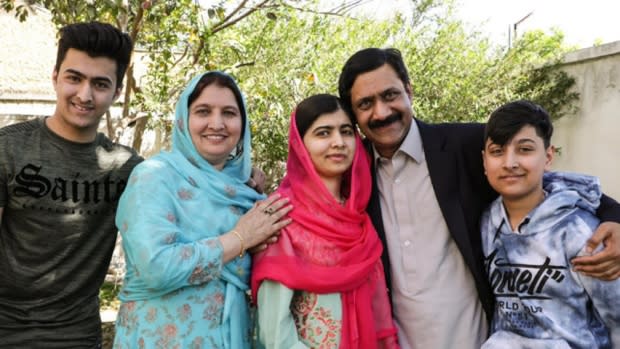

How to raise a Nobel Peace Prize winner: Ziauddin Yousafzai on being Malala's father

Ziauddin Yousafzai belongs to a small but mighty club.

It consists of men who are fathers to extremely special and talented individuals who become world famous at a tender age. Tiger Woods' father, Earl. Serena Williams' father, Richard. Wayne Gretzky's father, Walter. To that list add Ziauddin Yousafzai, father of Malala, the youngest ever winner of the Nobel Peace Prize.

Yousafzai was born to a traditional and deeply patriarchal working class family in Swat, northwest Pakistan, a place that would later become synonymous with the Taliban.

By his own account, Yousafzai as a boy had no confidence and a persistent stammer, a marked contrast to his daughter, whom he says seemed to be born with poise and precocity.

So how did he grow up to be a man with the confidence to break with tradition, set up a school dedicated to equal education for girls and boys and raise a daughter with the courage to defy the Taliban?

Yousafzai was recently in Vancouver to speak at the Women Deliver Conference. He sat down with The National's Adrienne Arsenault to talk about his journey to becoming an activist for gender equality and education, and what it takes to raise a girl like Malala.

On what it's like to be known as Malala's dad:

In patriarchal societies, fathers are known by their sons. And I'm one of the few fathers in the world who is known by his daughter. And I'm so proud of it.

Growing up in the Swat Valley in a patriarchal society:

Things have changed a lot now, but 40 years ago when I was growing up in a typical patriarchal family with five sisters under the same roof, I noticed that I had cream with my morning breakfast tea. My sisters did not. I had more clothes than my sisters. And the worst discrimination that crippled my sisters' future was that I was sent to school and they did not have that opportunity.

I will not blame my parents for that, because the government was like society ... also kind of patriarchal. There were many schools for the boys, but hardly any schools for girls. As a child I was not aware of it.

Like all other boys, I enjoyed being a special boy in a family. But later on, as a child I was mistreated by boys of my age because of my stammer. And some teachers too. They favoured the fair-skinned boys in the class. This was the discrimination I faced. So I was very conscious about inequality and discrimination.

How Malala got her name:

I named her after a legend of Afghanistan, a heroine named Malala of Maiwand who had her own identity. She was not known by her father, her son, or any other male family member.

How Malala became an activist for girls education:

In 2007, a BBC correspondent approached me and others who could tell the story of education in Swat [under Taliban rule]. And [at that time] Malala was really young. But she said "I will do it." She wrote it under a pseudonym, Gul Makai. She told the story of how education in the Swat Valley was suffering because of the Taliban's views and the destruction of schools, and the fear that children expressed.

Children were talking about the Taliban and war and conflict every day. She told this story through her BBC blog. Malala was the first girl ... who told her story. I tell people the first thing you do when you encounter human rights violations is to tell your story before it is twisted by your oppressors.

On finding out that the Taliban had attempted to assassinate Malala:

I was not expecting her to be attacked because in Pashtun culture, even in the worst of conflicts or feuds, a child and a girl is not supposed to be [a target]. The day she was attacked, I was at a press club and was about to give a speech. And a friend of mine just whispered in my ear — he told me that your school bus has been attacked. It was horrible news, but at that time I didn't know who was attacked. So I cut short my speech and said, "I have an emergency."

Reflecting on his guilt over what happened to Malala:

To be honest, it was such a tragic time. I forgot how to cry and weep. It was like I was sucked into a black hole. I'm the kind of person who asks himself, "To what extent was I responsible or what could I have done differently." And my wife said, "Please don't think like that. Never feel any guilt because you stood for the right of education and your daughter stood for the right of education. The people who are guilty are the criminals who attacked her."

Adjusting to life in England after the attack on Malala:

After about three or four years, we just accepted U.K. as our second home. It was very difficult in the beginning. [The] homesickness and nostalgia it was horrible to be honest …[but] we are so grateful to the people in the U.K., the great community who supported us and they helped in Malala's rehabilitation in every way.

Raising Malala's brothers in her shadow:

Me and my wife both grew up in a patriarchal family. Together, were able to create and build an egalitarian family. My sons believe in equality. They're living their own normal lives. They don't have any issue with having a sister who is a Nobel laureate. My younger son is into computer games; the older one has just finished his final school exams. They're living their own lives.

Words of wisdom for all the dads out there:

People ask me what I did for my daughter, and I tell them: "Don't ask me what I did, ask me what I did not do. I didn't clip her wings." This is especially important for the fathers in patriarchal societies. But to fathers all over the world [I'd like to] tell them that you should believe in your children, because if you don't believe in them nobody else will. You should be the first to believe in your kids.