RCMP 'sloppy' and 'negligent' in investigating Colten Boushie's death, say independent experts

Colten Boushie's family wasn't entirely surprised last month when a Saskatchewan jury acquitted Gerald Stanley of the murder of the young Cree man.

They had sensed holes in the RCMP investigation from the beginning.

"The RCMP did a botched-up job," said Debbie Baptiste, Boushie's mom. "They looked, and then they looked away."

Independent investigators agree with those concerns.

"It's sloppy work," said Michael Davis, a Toronto-based veteran of homicide investigations. "Obviously, the RCMP needs a lot more training."

The 56-year-old Stanley was charged with second-degree murder in Boushie's death, but a jury found him not guilty.

Davis is among several experts CBC asked to review the evidence and testimony presented at the trial in order to provide their own assessment of the investigation.

They are critical of the police's failure to protect the crime scene, as well as the decision to not send a key analyst to the scene in the aftermath of the shooting.

The federal police watchdog, the Civilian Review and Complaints Commission for the RCMP, announced Tuesday that it has initiated an investigation of the RCMP's original investigation to determine if it was conducted reasonably and whether race played a role.

Blood 'power-washed' from scene

When police arrived at Stanley's farm near Biggar, Sask., on Aug. 9, 2016, they found Colten Boushie face down on the ground in a pool of blood outside the driver's door of a Ford SUV.

Hours later, in darkness, RCMP Cpl. Terry Heroux took a handful of initial photos, which show significant bloodstains down the driver's seat, where Boushie was sitting when he was killed.

But when the RCMP left the scene that night, they didn't cover the vehicle or the area around it, leaving the driver's door wide open.

By the time forensic teams arrived on Aug. 11 with a warrant, more than 40 millimetres of rain had soaked the vehicle, washing away valuable blood evidence and potential gunpowder residue.

Heroux later testified that the vehicle was so drenched it had to air-dry for a day before the RCMP could process it.

"Your main concern is preserving the evidence, preserving the scene," said Davis. He said failing to do so is unacceptable.

"Somebody should have had the wherewithal to have gotten a tarp of some sort to protect that car," he said. "For a blood spatter expert to come and look at something like this, what would be the point? It's been contaminated — the blood pattern, everything has been washed away."

Blood spatter evidence lost

Joe Slemko, who has spent 25 years doing blood spatter analysis, described the failure to protect the scene from rain as "negligent."

"Especially when you are looking at a firearms-related event with very transient evidence that could be lost in a wind, let alone a strong or heavy rain," said Slemko, who is based in Edmonton.

"The evidence is gone. The damage is done."

The RCMP chose not to bring Sgt. Jennifer Barnes, an Edmonton-based blood spatter analyst, to process the scene in person and assess what transpired based on the physical evidence. Instead, she relied entirely on the photos.

Slemko reviewed the images of the vehicle entered as evidence. He said even the earliest photographs of the scene do not capture enough angles of the crime scene, were not taken using proper forensic techniques and the lighting does not allow for adequate analysis.

Had he been presented with these photos himself, Slemko said he would have been very hesitant to make an analysis.

"I just don't have enough information, and for me to provide an opinion on this evidence would be negligent on my part as an investigator."

'Not much of an investigation'

After being taken into custody on Aug. 9, 2016, Gerald Stanley was photographed at the nearest RCMP detachment, but was released shortly after and allowed to return the following day to file his statement.

Independent homicide investigator Michael Davis said standard protocol is to take statements as close as possible to the time of arrest. Davis believes the RCMP lost a lot by not taking Stanley's statement immediately.

"You're telling me that he was immediately released no sooner than getting to the detachment? I'd say that's not much of an investigation," Davis said.

When Stanley returned the following day, the RCMP did not bring in an experienced homicide interrogator to conduct the interview. Instead, it was a constable who conducted the interrogation, prompting the Boushie family's lawyer, Chris Murphy, to question the RCMP's dedication to the investigation.

Murphy has defended at least a dozen murder cases and was surprised the RCMP assigned a constable, the lowest rank among RCMP members, to one of its most high-profile cases.

"If I had been the commissioner of the RCMP," said Murphy, "and I knew this was going to be an important case for race relations, my immediate response would have been, 'I want everything done on this case that can be done.'"

Blood and gunshot residue are key to any shooting investigation. Where the traces end up can help establish where individuals were when a gun was fired and movement patterns afterward.

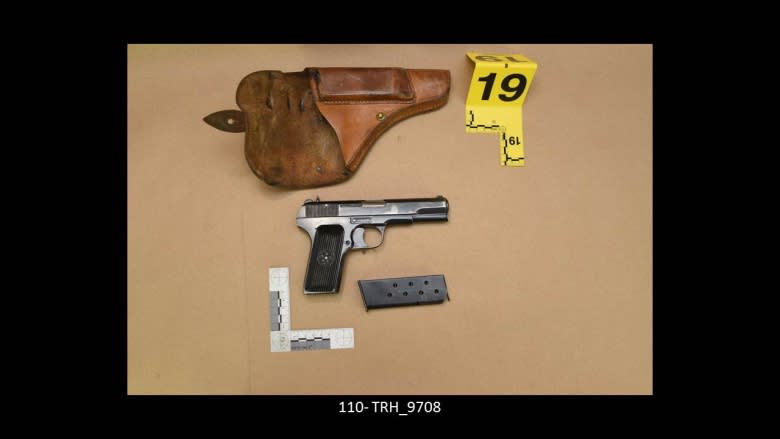

Gerald Stanley testified his handgun fired several seconds after the trigger was last pulled (known as a "hangfire"). He said he was attempting to remove keys from the SUV Boushie was in when the gun went off at extremely close range.

Typically, when a person is shot in close proximity, blood or powder would be found on both the shooter and the victim. While gunshot residue was indeed found on Stanley's hands and face — consistent with him holding the gun — only extremely small traces were found on Boushie's clothing. A forensics firearm specialist testified at the trial that it was not what he'd expect for a close-range shot.

Testing for residue

The experts CBC consulted said the vehicle could have had residue on it as well, but investigators did not test it.

Davis said he was surprised the vehicle wasn't tested. "Especially dealing with a firearm, that type of testing should have been done."

Stanley's clothing was another potential source of both gunshot residue and blood spatter, both of which could help determine his distance from Boushie when the shot was fired. But the RCMP never seized Stanley's clothes.

"That in itself to me could be crucial," said Davis.

"As a matter of proper investigative process, [the clothing] should have been seized," said Slemko. "Not just for potential blood stain evidence, but also gunshot residue."

The experts CBC consulted agreed that errors were made, but did not conclude it would have changed the outcome of the trial.

CBC asked the RCMP to respond to the critical impressions of independent investigators and the family's ongoing concerns. The force said it was unable to comment while the appeal period is pending. The deadline for the Crown to appeal is March 12.

The Boushie family's lawyer is intensely critical of the RCMP's overall treatment of the shooting.

"My honestly held belief is that the RCMP in Saskatchewan either does not know how to properly conduct a murder investigation — or that, in this case, they made the decision not to dedicate sufficient resources to it," said Chris Murphy.