Regina police fail to take domestic threat seriously, probe finds

Rebecca Stepan looked at her cellphone in horror. On the small screen was a photo of a man's hand clutching a noose tied in stark white rope.

"Check out what I learned how to tie … Looks good hey!" it read.

Her ex-husband had sent the message.

The same man has joint custody of their eight-year-old son, Charlie.

"All I know is when I see that," Stepan says, "over my dead body is he ever having access to my child."

For years, the 33-year-old says she has been the victim of stalking, harassing and threatening behaviour acted out by her now ex-partner.

But when she turned to police for help, they did not adequately investigate her complaints, according to an investigation done after she spoke to the Public Complaints Commission.

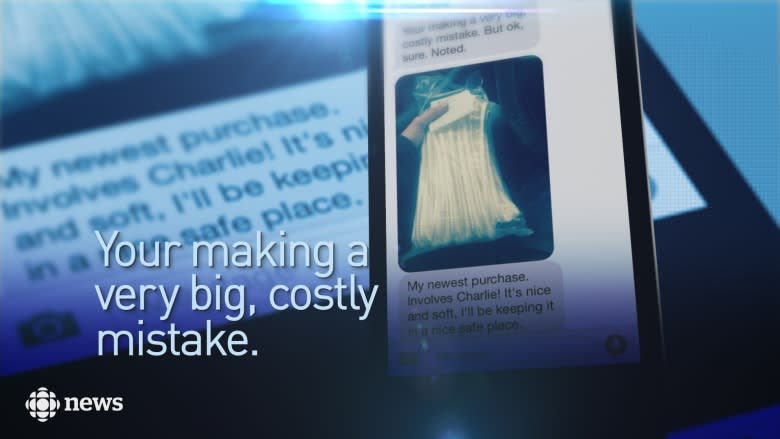

Just one month before Stepan received the image of the noose, in October 2015, she walked into the Regina Police Service headquarters with concerns over another text message.

It featured a photo of a hand holding a clear plastic bag with white rope folded inside and the sales receipt attached.

"My newest purchase. Involves Charlie!" read the note from her ex-husband. "It's nice and soft, I'll be keeping it in a nice safe place."

She showed the photo to the officer at the front desk. She told him that based on other recent domestic violence cases — Latasha Gosling and her three children had recently been murdered in Tisdale, Sask. — she felt vulnerable.

Stepan says the officer replied: "That's what's wrong with people like you. You see something on TV and you think it's happening to you."

Stepan stared at him. She was speechless.

"I didn't know what else to do," she says.

This is the sort of behaviour she has come to expect from police. Stepan has felt ignored despite repeated complaints of abusive behaviour.

"I was so sick and tired of going into the station every three to four months like clockwork and just not getting anywhere."

Complaint against police

This time, however, Stepan did something about it.

She filed a complaint with the Public Complaints Commission, which reviews concerns regarding municipal police officers in the province.

Cpl. Kyla Young, domestic violence co-ordinator with the Regina Police Service, encouraged Stepan to do so.

"I felt horrible for the way she was treated," Young says. "And because we had had prior issues that were brought to my attention about the front desk, I thought it was necessary for her to take this as far as she could."

An investigation into the incident, which included a review of the audio and video from the front desk, confirmed Stepan's account.

It says the officer "did not adequately examine and retain as evidence the text message that disturbed you and was rude and discourteous."

Supt. Corey Zaharuk says the Regina Police Service agrees Stepan was not treated appropriately.

"We found that the officer that she had contact with did not do what he needed to do in addressing her concerns," he says.

Zaharuk says Regina police get an average of 18 domestic incidents reported every day.

It's not surprising, in some ways: Saskatchewan has the worst rate of domestic violence and homicidesby intimate partners among Canadian provinces.

And it's not uncommon for victims of domestic violence to feel as though police are not taking their concerns seriously, says Jo-Anne Dusel, co-ordinator for the Provincial Association of Transition Houses and Services of Saskatchewan.

"Perhaps some police officers, if they've been in the field for a while, get frustrated when they see women remain in these relationships. That may lead them to not want to put a lot of time into it," Dusel says.

"What they don't understand is all of the reasons that women would stay, not least of which is their safety, as we know the most dangerous time for a woman is when she's leaving."

Hard to leave

Stepan says she has been trying to extricate herself from the relationship with her ex-husband almost since it began, when they were in their mid-20s.

He was controlling over her social life: Once, he threw an empty pint glass at her head when he spotted her speaking with someone else at a pub, Stepan says.

He trashed her apartment, too, she says.

She decided to leave but learned she was pregnant. So, they married.

"I think he liked to destroy things so he could have that honeymoon phase over again," Stepan says. "But as soon as it ended, it would go back."

When she finally called it off for good, he scaled the outside of her apartment building to her third-floor balcony. One time, he slept outside. Then, he tried prying the door off.

By the third attempt, Stepan says, it was enough to send her ex-husband to jail for mischief and violating a restraining order.

Soon after that, she filed for divorce. Her former spouse moved to another city and, for a while, there was a reprieve.

But then Stepan and her ex-husband were granted joint custody.

And the text messages started coming in again.

Likely to reoffend

There are risk assessments to determine how likely an offender is to escalate his behaviour. When Dusel administered one to Stepan, her ex-husband ranked within the highest risk category to reoffend.

This September, Stepan says her ex-husband surprised her outside her home. She says he got in the car with her. When he refused to get out, she drove him to the police station and he took off on foot, she says.

When she made a report, she says police told her "nothing criminal" happened.

But Zaharuk says determining that takes time.

"I can tell you that the concerns that Ms. Stepan has brought forward to us are still under investigation and I'm not here telling you today that these matters are not criminal. I certainly suspect that they are criminal, but the investigation is ongoing to determine that."

As for her experience reporting the text message, Zaharuk says the officer involved has had his behaviour addressed and the police service is providing more training and guidance to all of its front desk officers.

Zaharuk says Stepan's concerns are now part of a police file and the information has also been shared with police in the city where her ex-husband now lives.

Mom fights ex's access to child

With the way in which the justice system handles custody matters, Stepan says women like her are in a no-win situation — one she calls a double bind.

"The justice system allows these people to have joint custody who really shouldn't when there is a restraining order," she says. "Because of that, police can't access their rights to prevent him from being near me because I have to deal with him."

CBC News attempted to contact Stepan's ex-husband through his lawyer, but he declined to comment.

Stepan would prefer the case went back to court, so she could ask the judge for another no-contact order. The previous one — following the balcony incident — has expired.

She says for now, she will continue to follow police advice to ignore any contact from her ex-husband — contact that his lawyer promises will continue until she grants access to her son.

In a letter sent Oct. 24, the lawyer says Stepan's former partner "has been and will continue to contact you each week to set up a time for a phone visit."

It notes that a court order from 2012 allows "reasonable" access.

"If you do not co-operate with these telephone and personal visits, you are disobeying the court order. Some professionals assert that a parent who obstructs visitation is engaging in a form of child abuse," the letter ends.

Stepan says the text messages of a noose make that impossible for her to do.

"They'll have to take me to jail before he'll ever gain access to my child."