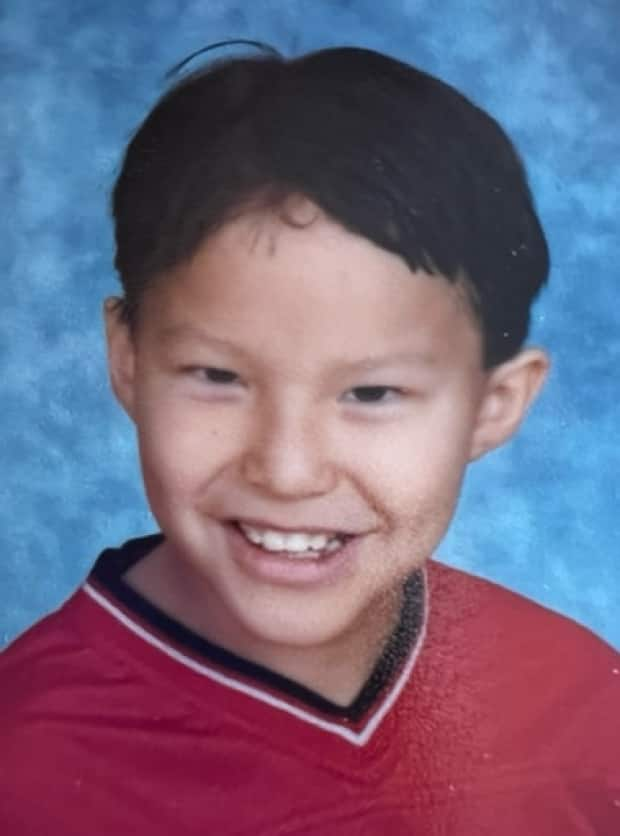

Remembering Travis Smarch, another victim of Yukon's drug crisis

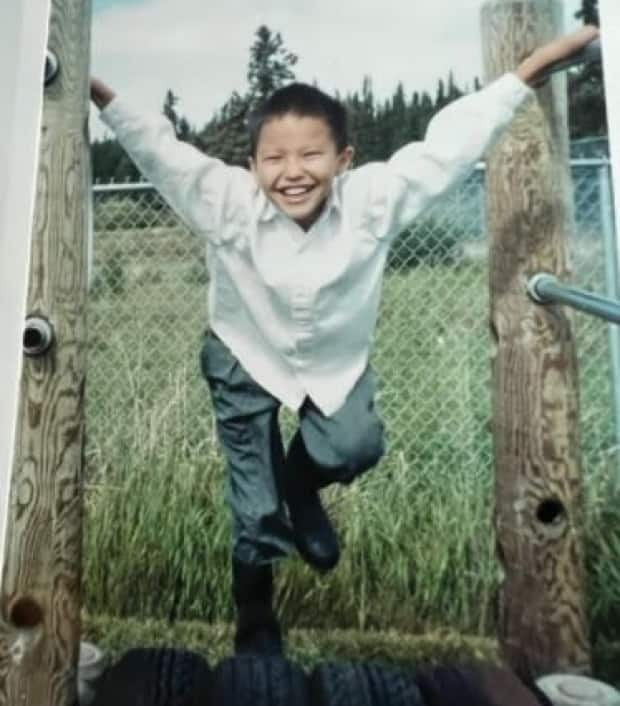

Travis Smarch was known to everyone around him as an adventurous, outgoing and funny young man with a bright future.

His life ended abruptly on Jan. 5 — the day he overdosed, alone, in his room at Whitehorse's Chilkoot Inn. He was just 27.

"It's been really hard for me to talk about my son, because it's so fresh," his mother, Rosemary Smarch, told CBC News. "It's like my mind's blank."

He is one of eight Yukoners who have died from an illicit drug overdose so far in 2022. In response, the Yukon government declared a substance use health emergency last week, in an effort to bolster addiction and mental wellness services.

His family, still grieving their loss, shared their story in hope that it will spur change.

Travis grew up with his mom, his older sister Robyn and younger brother Sylas between Carcross, Yukon, and their home on Jeckell Street in Whitehorse.

His uncle John Smarch remembers how Travis used to take off all the time, running down the street toward the river to go fishing.

"He'd always be looking for grayling and that to bring home to his mom," John said. "He'd be so happy when he caught fish [because] he'd be like, providing for [her]."

When Travis got older, he'd start cooking for his family and friends too, his mom recalls.

"Wherever he went, it didn't matter … who he was with, he would always want to cook for them," she said.

Travis fostered a dream of eventually going to culinary school, but that never came to be.

The other love of his young life was animals, John said.

Travis had a particular affinity for Bam Bam, the family dog.

"One time we're out visiting Auntie … and we were looking around outside and couldn't find Travis anywhere," John said. "My mom started getting really worried.

"I happened to be walking by the dog house … and here [Travis] was, curled up and hanging on to his dog, snoring away."

John says he could've seen a future for Travis where he worked as a veterinarian, and would come home to a nice, stable home with a wife and children at the end of the day.

'Such a strong hold'

Things started to change with Travis in the four years before his death, Rosemary said.

At first, Travis wanted nothing to do with drugs.

Eventually, he gave in, joining a social scene where drugs were ever-present.

Travis was hooked from then on.

"It just had such a strong hold on him," Rosemary said.

"I felt completely and utterly hopeless because all you can do is talk to your child and pray that … one day they'll want treatment."

John knows this pain.

He sought treatment through a few detox programs and at Jackson Lake, an on-the-land program, for his own addiction a few years ago. He tried to use this life experience to convince Travis to go for help.

Travis went through stints without using, but, long term, nothing really stuck, John said.

"I was just trying to tell him that it's not a life … there's more to life than using drugs and alcohol to cope," John remembers.

"You have to learn to talk, you have to tell people when things are going on."

'We need change'

Both Rosemary and John say it's been challenging for them to come to terms with losing Travis — not only for them, but for their entire community.

Several of the eight people who died from illicit drugs this year are members of the Carcross/Tagish First Nation, including Travis.

"The community right now is really devastated," Rosemary said. "We're all grieving the loss of our citizens. We need change, and we need it now."

Both say there needs to be something done locally, like a group session with elders, to show users like Travis another way forward.

One of the reasons Travis had a hard time with treatment, Rosemary says, was because he didn't want to tell a stranger about what was going on in his life.

She says she thinks if Travis had the chance to talk to an elder, it could have really helped.

"That really does connect people," she said. "So they know they're loved. Because stories they're going to share with them ... [are not] going anywhere else."