Report for America: Essays from across the USA

USA TODAY Opinion is partnering with The GroundTruth Project to publish essays written by Report for America corps members sharing their perspective on the communities where they live and report. Below, find links to the latest essays:

Homeless children need a chance — LeBron James' program gives them one in his hometown

AKRON, Ohio — LeBron James’ basketball career started in a place similar to this: huddled around a hoop on a tucked-away Akron street, with friends wiping their brows as beads of sweat, illuminated by a nearby porch light, dribbled down their faces.

London Riley, 10, is determined to score on her much older rivals; she darts across the rain-slicked court, nimbly dodging the defense before sinking a basket through the hoop. Riley is one of 20 Akron students living in the LeBron James Family Foundation’s new transitional housing complex who didn’t always have a safe place to play outside, or even live.

But on this late-October evening, she can just focus on the game.

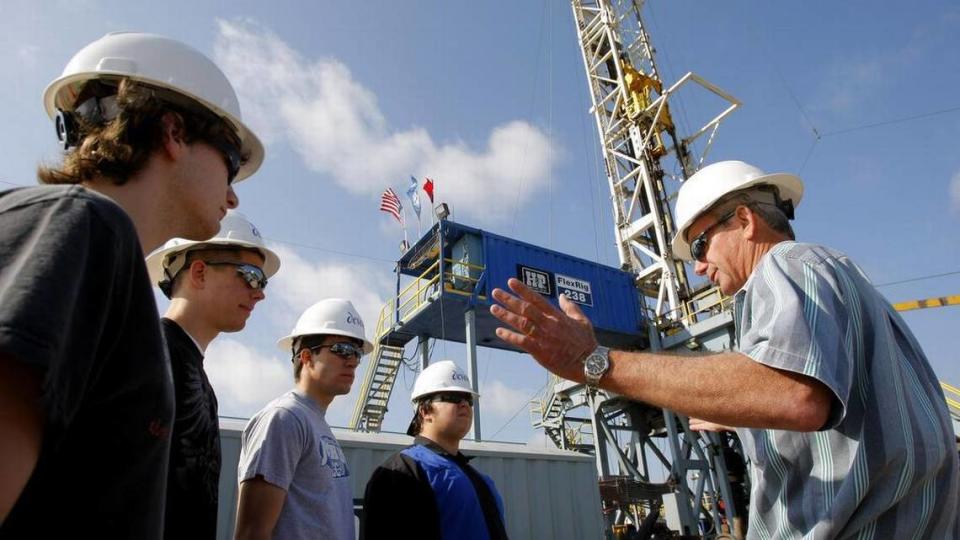

In Texas, environmental activists renew fight against fracking

FORT WORTH, Texas. — The vast majority of rigs that dotted the landscape here more than a decade ago are long gone, along with the economic boom that natural gas drilling brought to North Texas.

But a regional resurgence in hydraulic fracturing this summer dredged up tensions between anti-fracking activists and local government leaders.

Over the summer, French energy giant Total submitted at least 26 new gas well permit requests in Fort Worth-area cities, leading to renewed calls for action from local activists concerned about the environmental impact of drilling.

In California, people lived on the edge of homelessness before COVID-19. Now, it's worse.

SILICON VALLEY, Calif. — Sarah Rivas was barely making rent since she’d move to Sunnyvale, in Silicon Valley, California. When, three months into the pandemic, she woke up to an email from her school announcing a nearly 7% cut in teachers’ pay, she gave up a three-year battle.

“I moved into my parent’s house,” said Rivas, who’s been teaching her class of 12th graders from Sacramento, three hours from their high school. “Not what every 26 year old wants to do.”

Should cops be in schools? Police reforms divide a community in California.

FRESNO, Calif. — At 9 p.m. in late August the Fresno Police Reform Commission was four hours into its fourth general meeting when members began to debate whether school resource officers should wear polos instead of uniforms.

“We would like them to be in street clothes or their police polos, shorts, jeans. We don't want them walking around in their combat uniform,” said Keshia Thomas, president of the Fresno Unified School District and one of the 37 members of the commission.

Vulnerable Kansas bird populations are a canary in a coal mine for climate change

WICHITA — It has been five months since Virginia Soyez died on a Monday in March, but every morning her husband Frank keeps their tradition. He wakes up at 5:30 a.m. — a habit that hasn't left him since his days as a tank mechanic — and sits in a brown recliner across from its now-empty pair in the sun room. He sips weak coffee from a brown and tan ceramic Fort Scott mug decorated with a sprig of wheat and foregoes breakfast altogether, as there's no longer anyone to share it with.

Undocumented in Pennsylvania: An immigration activist stays defiant despite Trump policies

HARRISBURG, Pa. — Looking out onto the Susquehanna River earlier this month, Stephanie Nuñez sat under grey skies as the rain trickled. The riverfront is blocks away from the bustle of Harrisburg, the tightly packed brick homes of the city and the state Capitol.

Nuñez says this is where she sometimes comes to run and clear her mind.

The past couple of months have been a whirlwind as President Donald Trump flip-flopped between supporting people like Nuñez, who were brought to the United States as children without proper immigration documents, and threatening to end the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrival program, the legal provision that’s protecting them from deportation.

But Nuñez, an organizer for the Movement of Immigrant Leaders in Pennsylvania (MILPA), says she is neither weary nor intimidated.

When COVID-19 forced schools to close, child hunger surged in West Virginia

CHARLESTON, W.Va. — Jessica Smith lives with her family in the small town of Belle, about six miles from a high school where nonprofits provide free meals to families in need.

But, like several other families who qualify for the program, Smith, a 39-year-old mother of two, does not own a car, making it difficult to leave her isolated home to get food.

“We’re just stuck with no way to get lunches,” Smith said. “I’m having to scrape up stuff for my kids… My son seems like he’s never full.”

In Detroit, immigrants paint a rich tapestry of community and culture

DETROIT — At the intersection of Dequindre Street and 8 Mile Road, the dividing line that separates the city from its predominantly white suburbs, a group of protesters recently marched against police brutality. They stretched to the horizon on the normally bustling street as neighbors stood on either side with their fists raised, chanting in support.

Eight Mile is a symbolic place in the minds of Detroit residents, who share a common past of housing disparities and redlining. The marchers joined the waves of civil unrest sweeping the nation, passing Motor City gas stations and auto repair shops along this historic stretch, home to more than 1,500 businesses.

In Chattanooga, faithful persevere as coronavirus, tornadoes hit

CHATTANOOGA, Tennessee — Nothing moves in this city without the churches. This is a region run largely by preachers at the pulpit, not politicians who win the polls. Tennessee Gov. Bill Lee knows this, and his executive orders to stop the spread of COVID-19 reflect it: Churches are essential.

In any other time of crisis, there come the churches. They set up tents to care for the poor and comfort the sick. They are the ones leading marches. They mobilize recovery crews and organize community meals. But, as we all recognize, these are not normal times, and the institutions that hold together life in Chattanooga, and much of America, are searching for their footing during this pandemic.

Coronavirus threatens people living in shelters. Here's how an agency rushed to save them.

NEW HAVEN, Connecticut — Columbus House typically bustles with staff doing laundry and cleaning beds as volunteers prepare and plan meals for people who are homeless. When people in need arrived at the shelter in the late afternoon looking for dinner and a place to spend the night, they’d find food and a bed.

Now, the shelter sits mostly empty. The lights are off and hallways are quiet as most of the staff work remotely during this pandemic. Their jobs now include racing to move an unprecedented number of people out of shelters and into alternate housing, including hotels, to avoid spreading the coronavirus among one of the most-at-risk populations.

Life in Paradise: A deadly wildfire raged. Then the pandemic hit.

CHICO, California — Business was finally picking up in Paradise, the Northern California town devastated 17 months ago by the deadliest, most destructive fire in the state's history. Then the COVID-19 pandemic hit.

Butte County has seen few hospitalizations and no deaths from the coronavirus. But the crisis highlights the area’s health, social and economic vulnerabilities. The county has more people older than 65 than the state average, according to the 2019 Community Health Assessment, as well as slightly higher percentages of hypertension, kidney disease, pulmonary disease and asthma. The only hospital in Paradise closed because of damage from the Camp Fire, which killed at least 85 people and destroyed about 14,000 homes.

Changes brought by the pandemic to daily life in Paradise have tested residents' hard-earned lessons on survival and resilience.

In California farm country, growers struggle with labor shortage

Across the nation, there is a tendency to reduce California to its economic heavyweights, Los Angeles and the San Francisco Bay Area.

But in a state that extends more than 163,696 square miles, with a population pushing 40 million, there’s far more to life here than Hollywood or Silicon Valley. Each of California’s major regions — Southern California, the Inland Empire, the Central Valley, Bay Area, Northern California — carry their own identities, and their nuances are easily overlooked.

In rural Utah, local journalism shrinks as government controversies grow

BLUFF, Utah — Drought maps of the southwestern United States looked like a target in 2018, dark red ringing a brown bulls eye. The center, indicating the most severely dry region, was on top of my home in San Juan County.

Snow and rain that winter brought relief, but in May, the region began to slip back into drought. Where I live in Bluff, a tiny town along the northern edge of the Navajo Nation, there wasn’t a soaking rain all summer. Humidity was so low at times that when I pet my cat, we both got a static shock. My laying hens scratched around the yard, looking for insects that had long since disappeared.

San Juan is the largest county by geography in Utah and one of the largest in the nation. It fills in the entire southeast corner of the state, stretching from the Colorado River across tangles of canyons, bare mountain peaks and high farmland to the arid Navajo Nation and lands belonging to the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe.

Life under a bridge: In California, children enduring homelessness face daily hardships

MODESTO, Calif. — After a dip in the Tuolumne River, a 10-year-old girl who didn’t know how to swim but had no fear of the river chatted with her “street sister” in their invented language, crafted so they had something private in their otherwise exposed lives.

The July sun sizzled as the tent city approached 100 degrees, and with no breeze or electricity, a swim in the Tuolumne was their only relief. The two girls, who reverted to English when they wanted to discuss rap songs, school or surviving on the streets, were drenched from head to toe as they headed barefoot under the Ninth Street Bridge.

Fighting for health care: Rural America struggles with loss of doctors, clinics

FAIRFIELD, Washington — Drive 20 minutes south of Spokane and pine trees give way to rolling hills, which in fall are golden with remnants of the wheat harvest and in winter dusted with snow. This part of eastern Washington state is the beginning of the Palouse region. Its small farm towns once thrived but now struggle to offer essential services such as health care.

For decades in Fairfield, residents received care from a doctor in a community clinic on Main Street. Alongside a post office, community center (which doubles as Town Hall), drug store, bank and library, a stucco building where the health clinic used to be sits vacant.

Longtime Fairfield residents recall giving birth to their children at the clinic and visiting for regular checkups. But in 2019, after Kaiser Permanente acquired the health care group that operated the clinic, it closed and the doctor moved to Spokane, a 30-minute drive north.

Poverty still plagues West Virginia, but signs of hope can be found

CHARLESTON, West Virginia – Last June, I was dispatched home to West Virginia as a Report for America corps member to cover poverty for my hometown newspaper, the Charleston Gazette-Mail.

Our corner of Appalachia is rooted in poverty — think black and white images of Lyndon B. Johnson’s “War on Poverty." Today, West Virginia remains one of the poorest states in the country, where one in five children struggle to access food. The history and policy failures here — our vulnerable children, cyclically disadvantaged — are complex in a place where despair lingers in the damp air between rolling hills and in people who can’t “just pick up and leave,” as outsiders advise, or who simply object to doing so.

The story of West Virginia’s entrenched poverty is told in data points, which land the state at or near the top of ominous national rankings: worst health, worst education levels, worst employment. But it is often more nuanced than that. A puzzling factor of the state’s ailing economy, for example, are our rolling mountains, which isolate towns from sorely needed industry and internet access, especially in "coal country" in the southern part of the state.

To fight health disparities, Native Hawaiians return to their agriculture, wellness roots

HONOLULU — Up Highway 93, on the Hawaiian island of Oahu's west coast, the crisp air and crystalline water beckon from Makaha Beach. Urban Honolulu and touristy Waikiki fade into the distance. Here, one can imagine an ancient Hawaii, of shores pocked with salt ponds and deep valleys flushed with kalo loi, or taro fields.

Centuries ago, before the golf resorts, fast-food strip malls, dialysis centers and waste landfills, Oahu was divided into land slivers, called ahupuaa, which still mark the land from summit to shore. Native Hawaiians used the ahupuaa system — a socioeconomic, geographic and climatic subdivision of land — to sustainably source food in tune with the seasons, never taking too much, sharing with neighbors and caring for the earth in return for the bounty it provided, a traditional practice today’s locals are trying to revive and maintain.

In the Afro-Caribbean heart of Puerto Rico, locals fight erosion, government indifference

LOÍZA, Puerto Rico — The waves crashed loudly on the collapsed ruins of the Paseo del Atlántico, a walkway that once partially protected residents here from the volatile ocean. Erosion along this northernmost coast of Puerto Rico, nearly 20 miles east of San Juan, precipitated the promenade's destruction for more than a decade and, in 2012, it finally fell into the Atlantic, exposing the Parcelas Suárez neighborhood to the water's edge.

Its 1,560 locals now fear daily for their homes and lives.

Connecticut's 'monument' to tough-on-crime era sits almost empty as justice reforms shine

SOMERS, Conn. — It’s not the rows of barbed wire along the building’s exterior, nor the locked metal door at the entrance. It’s not the buzzer for requesting entry, nor the distinct lack of windows; not the guard at the entrance and not the metal detector. It’s the thick, stale air inside Northern Correctional Institution that cuts you off from the outside world. The trapped oxygen between its silvery, worn floors and ceilings, caught between narrow hallways and cinder-block walls, lock you in.

The prison is a “monument” to another era, when officials locked up the “worst of the worst,” Dan Barrett, American Civil Liberties Union of Connecticut’s legal director told me during the course of my reporting on the facility. “I see Northern as the apex of a failed model.”

I returned home to report on poverty in California. We're strained, but not broken.

SAN JOSE, Calif. —The first thing locals mention are the homeless who line the streets of densely populated city blocks. They sleep restlessly in RVs; in vast encampments under the freeway; in tents in front of artisan coffee shops; on scraps of cardboard and discarded mattresses; on subway car seats that lurch from one end of town to another.

This is the Bay Area in 2020, infamous for its homelessness crisis and rising inequality, where the gulf between the rich and the poor can be seen every day on the street. Tents are propped up in front of swanky restaurants and boutique gyms; the impoverished pick through techies’ trash; misery laps up against luxury, all while the elements rage — fires, earthquakes, drought.

How many women in Puerto Rico must die before there's change? Women are done waiting.

SAN JUAN, Puerto Rico — Women from multiple generations walked together late last year down trafficked avenues flanked by government buildings with a view of the Atlantic Ocean.

Some held their daughters’ hands; others held signs reading, “Peace for all women” and “Justice, respect and equity." They joined others, many wearing purple as a symbol of resistance against patriarchy, transforming the marchers into a single color wave that descended onto San Juan. They chanted to demand a tally of how many women must be killed to cause an official acknowledgement, and reaction.

Reporting on climate change from Cape Cod, where sea levels could put everything at risk

WOODS HOLE, Mass. — As you jog along the curving 3-mile road that leads down to the water on the southernmost tip of Cape Cod, you’ll pass five of the world’s leading marine and environmental institutions.

You’ll glimpse the solar arrays and wind turbine of the Woods Hole Research Center, where scientists and scholars study climate change and its impact around the world. You’ll wind your way past our local U.S. Geological Survey center, within the Quissett campus of the famed Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Just as you begin questioning why you started running in the first place, you’ll hit the Marine Biological Laboratory, a private nonprofit affiliated with 58 Nobel Prize winners since 1929. And finally, after passing exhausted doctoral students working in the coffee shop, you’ll reach the harbor by the national marine fisheries services.

I grew up amid addiction, abuse. Now I report on similar stories so no one is forgotten.

BUFFALO, N.Y. — In the nearly 2,300 miles between here and my hometown of Las Vegas are the stories of resilience I’ve always wanted to tell. They’re the stories of people who were brought to their knees by life and somehow got back up: childless mothers, traumatized veterans and sex abuse survivors.

I cover mental health for a local cable news station in Buffalo, known in its glory days as "Queen City," when it was the largest and most prosperous on the Great Lakes throughout the 19th century. To get here — now a glimmer of its former self, slowly recovering from decades of decay — my father and I drove from Las Vegas through the Rocky Mountains, and the Denver I knew a decade ago when I bounced among family members and watched as my biological mother battled her addiction and lost each time. I grew up in halfway houses and took beatings so bad, the bruises blossomed for months after the blows that caused them landed.

How wildfire victims are rekindling community a year after devastating, deadly Camp Fire

PARADISE, Calif. — In October, hundreds more Californians joined the ranks of those who’ve lost homes and businesses to wildfire as hurricane-force winds blew flames through the vineyards of Sonoma County and the chaparral on the outskirts of Los Angeles. The news media told a story of grief and destruction. The coverage was dramatic enough that some have started questioning why people are living in California at all.

A year ago, it was Paradise in the spotlight. On Nov. 8, 2018, fierce winds blew a spark from Pacific Gas and Electric Co. equipment into bone-dry trees, then pretty wooden homes throughout Paradise and other remote communities in Butte County. The resulting Camp Fire became the deadliest and most destructive fire in California history, burning nearly 14,000 homes and killing 85 people.

Teaching the blues to Mississippi Delta kids shows them they have a culture to be proud of

GREENVILLE, Miss. — I recently moved to the heart and soul of the Mississippi Delta, the birthplace of the blues. Signs of this rich music heritage are all around me in this part of the state — the town where B.B. King was born, the railroad station where “Father of the Blues” W.C. Handy first heard the blues and, perhaps most famously, “The Crossroads.”

This crossroads is not just any intersection. Legend has it that blues musician Robert Johnson came to this place where Highway 61 and Highway 49 meet and sold his soul to the devil in order to play guitar — and that it inspired his famous song “Cross Road Blues.”

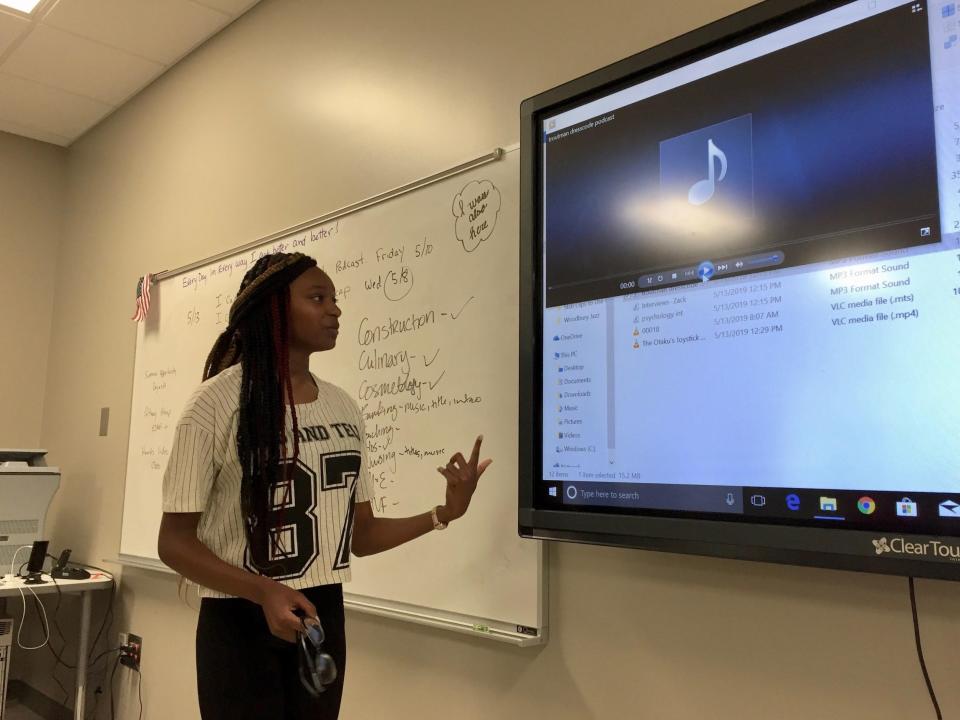

Kids, teens have their own stories to tell. Reporters like me should be ready to listen.

MACON, Ga. — Jy’Nivea Troutman hides on the floor of her bedroom when she hears gunshots outside her window. That’s just what you do on Saturday nights in her neighborhood, she’ll tell you.

But Troutman, 16, would much rather talk to you about her school’s dress code. She thinks that her school’s policy is too strict — and that girls are more likely to be penalized for wearing what they love. She even made a 16-minute podcast episode about it.

Out here in New Mexico, life and death flow at the pace of the vulnerable Rio Grande

ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. — El agua es la vida. Water is life.

Doris Rhodes knows that mantra well. She inherited a riverside property from her father about an hour south of the city more than a decade ago. The land, in arid Socorro County, is nestled against the Rio Grande. Sprawling along 629 acres on the east side of the river, where there are no levees, it is one of the few wetlands in the area.

My print-only local newspaper won't chase Twitter likes, Google searches — just the story

BUFFALO, Wyo. — The paper was late.

Normally, the newest weekly edition of the Buffalo Bulletin hits our rack just before 1 p.m. on Wednesdays, driven 40 miles down Interstate 90 from the printer by a Bulletin employee.

Our readers know the schedule, and Wednesday afternoons in the newsroom are regularly punctuated by the jangle of a large, brass cowbell hanging off the push-bar of our glass front door. Folks offer a greeting, peel a paper off the stack and drop a dollar in the wooden bowl on the front-desk countertop. Subscription copies arrive with Thursday’s mail, but many are unwilling to wait.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Report for America