Rise of Spanish populists overturns two-party system

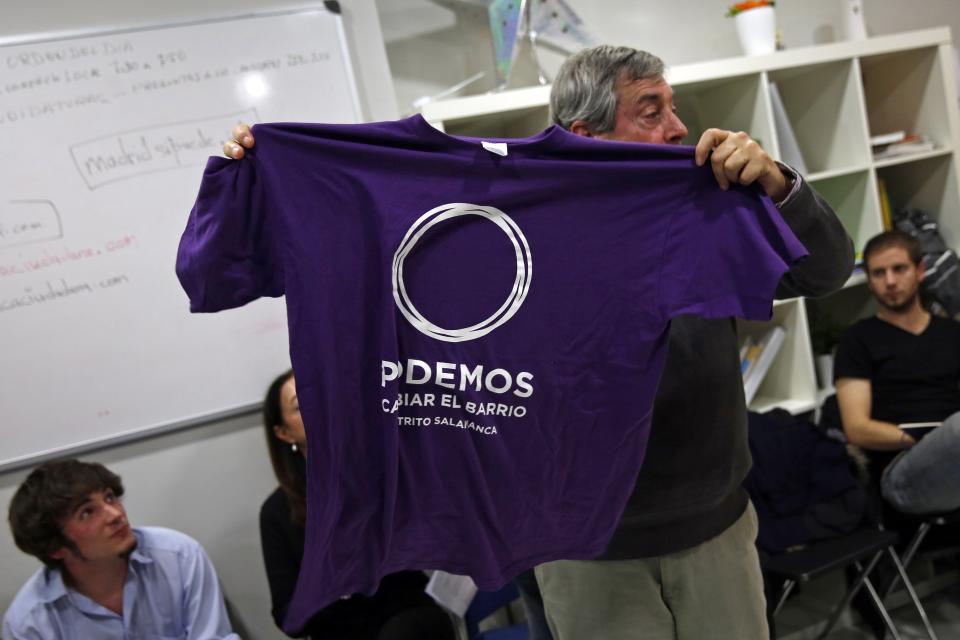

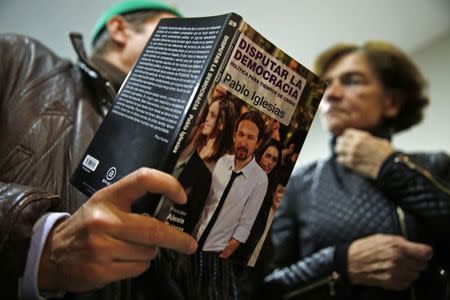

By Julien Toyer MADRID (Reuters) - The sudden rise of a new anti-establishment party has transformed Spanish politics a year before a general election, forcing the center-right government to veer away from austerity and the left-leaning opposition to scramble for new leaders. In just a year since its founding, the party "Podemos" - We Can - has overturned the two party system in place since Spain embraced democracy in the 1970s. It is now polling around even with the ruling People's Party (PP) and main opposition Socialists, and has even led in some polls. Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy's PP has unveiled a raft of new, populist-tinged measures, such as an anti-corruption bill, new monthly payments for the long-term unemployed and the first rise in the minimum wage in two years. The Socialists have replaced their leaders in search of fresh faces that would have more electoral appeal. Further to the left, the former Communists have announced similar plans. But Podemos activists say the mainstream parties are missing the point: their group offers not just new personalities and a new policy mix, but a whole new way of thinking about politics, giving greater voice to ordinary Spaniards who feel ignored by a political class derided as "la casta" or "the caste". Podemos has set up hundreds of local assemblies known as "circulos" across the country, staging unruly weekly meetings at which Spaniards can vent the anger built up during worst economic crisis since World War Two. "The one thing we all share is the outrage over what's going on in Spain," said Jose Luis Soriano, a 32-year old unemployed computer scientist who has been coming to the circulo in the upscale Madrid neighborhood of Salamanca since the summer. The Salamanca circulo now has about 500 members. Each week about 50 people attend its meetings in a rented private school classroom. They come from all walks of life and political backgrounds: pensioners, students, housewives, executives. "I like the fact that they're open to debate, transparent and want to change this rotten system," said Soriano. Those who attend describe the meetings as an experiment in democracy. There is no leader; members can attend whenever they like and they vote on everything - from organizing a Christmas contest with local shops to choosing who will be their representative, to their policy platform in a local election. Created in January by a group of political science professors from the Complutense University in Madrid and led by charismatic 36-year old Pablo Iglesias, the party is tapping into the sentiment behind the "Indignados" movement of youths that occupied Spanish squares in 2011. UNPREDICTABLE With nearly a third of voters still undecided, Spain's election, and the impact of Podemos, is still hard to predict. A Dec. 7 poll in El Pais predicted Podemos would place second with 25 percent of the vote, just below the Socialists with 27.7 percent and ahead of Rajoy's PP with 20 percent. A poll two weeks earlier in El Mundo said Podemos would win with 28.3 percent of the vote, with the PP second. Polls have shown Podemos taking more votes from the left than from the right but still eating into both main parties' support. Some analysts believe Podemos may have peaked too soon and could find it hard to translate its early support into votes in a year's time. Last month it issued new economic plans that toned down some of its initial radicalism. Nevertheless, investors are watching the phenomenon closely in a country where the euro zone crisis of the past three years has seen political volatility translate swiftly into big swings in interest rates. "Companies are racing to issue debt ahead of next year, when the political horizon is getting cloudy and uncertain," said a source at one of Spain's biggest companies who asked not to be identified because he did not want to draw attention to his firm. There are clear parallels to the rise of populists in other crisis-hit southern European countries. In Greece, the far left Syriza party emerged as the main opposition after the mainstream Socialists withered. In Italy, the sudden rise of comedian Beppe Grillo's Five Star Movement scrambled both the left and the right until Socialist Matteo Renzi emerged as prime minister. "The most likely scenario after next year's elections will fall somewhere in between pre-Renzi Italy and today's Greece: three large blocs - left, right and populists, like in Italy - with the socialists emerging last - like PASOK in Greece, though not likely as low," said Eurasia Group analyst Antonio Roldan in a note to clients. Rajoy's entourage is betting on fear of instability to lure back some of the 5 million voters that have abandoned his PP since 2011. The Socialists expect long-time backers now flirting with Podemos to balk at the last minute. Business leaders and some in both parties are hopeful the two mainstream groups can agree a grand coalition to govern if necessary, although both have ruled out this scenario for now. That would give Podemos an opportunity to shake things up from outside the system, like Syriza and the Five Star Movement, which have both been kept from power so far but have transformed debate in Greece and Italy from the opposition benches. But that is not the scenario that suits Luis Maestre, back at the Salamanca circulo. A 56-year old civil servant who voted for the socialists and the communists for 40 years, he now wants to run for a seat in Madrid town hall under the Podemos banner. "The system can only be changed from the inside. We want to seize local, regional and national power. We want to blow over the political chessboard and move the pieces around." (Additional reporting by Andres Gonzalez in Madrid and James Mackenzie in Rome; Editing by Peter Graff)