Rural reboot: Salinas, Calif., turning crop pickers into computer programmers

Whenever Adilene Constante passes one of the strawberry fields that rings the city of Salinas, California, she studies the little figures bobbing up and down in the distance, knowing there's a chance that one of them might be her mom, bending an average of 10,000 times a day.

"My parents work in the field all year round," Constante says. "They've worked a variety of crops, from grapes to onions to strawberries to almost any crop that grows here in the Salinas Valley.

"My dad would take day shifts, then come home, sleep for three hours, then go back to work a night shift. I didn't want a life like that for me," she says.

Now Constante is embarking on a completely different kind of life, thanks to an innovative college program and efforts to rebrand Salinas as the agricultural corollary of Silicon Valley.

Salinas Valley is only 45 minutes' drive from Silicon Valley, but it seems worlds away. The valley produces 80 per cent of the country's lettuce, but it's also known for something far less appetizing: poverty and crime.

"I'll be the first to admit that," says Salinas mayor Joe Gunter, who was a police officer here for 33 years. His city of just over 160,000 people recorded almost 40 murders last year and is on track to equal or surpass that number this year.

"The gangs are part of the problem, methamphetamines and drugs is the other one," Gunter says. "Some of it is caused by the fact that poverty is a problem, lack of a good education for some of the young people, so we're working on those issues."

Low education levels in Salinas

Salinas is California's youth homicide capital, according to the Violence Policy Center, and also the second least educated city in the U.S. Most youths end up working in either the fields or the streets.

Zahi Atallah, Hartnell College's dean of advanced technology, drives through Salinas' notorious east side, pointing out the cheap, high-density apartments that line both sides of the road.

"Only 12.5 per cent of the population has a bachelor degree or higher," Atallah says. "The vast majority work in agriculture."

But now his college has opened another path, turning the children of pickers into programmers.

Computer science degree in 3 years

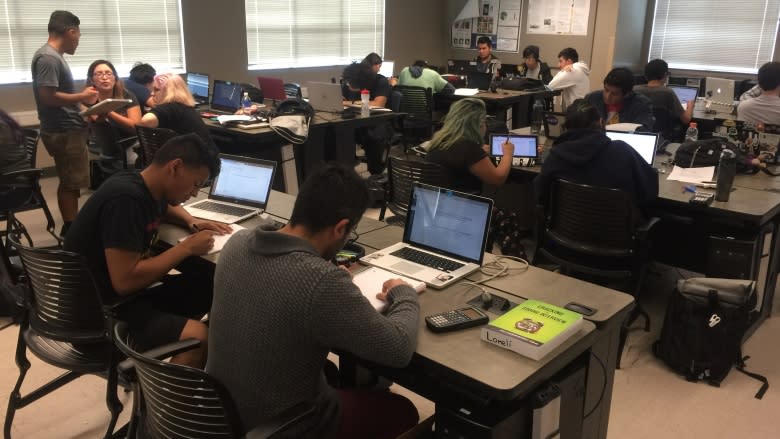

Hartnell's CSin3 program is giving its students — 70 per cent of them Latino and about half of them women — a shot at earning a degree in computer science in three years instead of four.

Many of the 36 students in the program are eligible for a full scholarship paid for by the Matsui Foundation, founded by Andrew Matsui, who emigrated to the U.S. and became the nation's largest orchid grower.

"On average, nationwide, the graduation rate [for computer science programs] after four years is less than 45 per cent," Atallah says. "Our first cohort graduated this past May with 72 per cent of the students, and within four years we will have close to 92 per cent having graduated."

He credits extracurricular support, like tutors, and financial support — free tuition allows students to focus on their education rather than split their time between school and a job.

Young grads at work

And what percentage of them will get jobs in technology? All of them, says Atallah.

In a shared office in downtown Salinas, Leticia Sanchez, 28, is hard at work ironing out compatibility issues with an app. But it's child's play compared to packing lettuce by her mom's side, the hot metal breath of the packing machine always just behind her.

"I was thinking that's how it's going to be my life, for the rest of my life," says Sanchez, in her third and final year of CSin3.

Instead, she'll be the first in her family to earn a degree of any kind. And while she's studying computer science at Hartnell, she's interning at an ag-tech startup called HeavyConnect, using what she learned picking crops to help design an app.

"I was able to contribute more ideas on how to create something to help the farmers," she says.

The program is so successful in large part because of efforts to reboot Salinas as an agricultural technology centre. The Western Growers Association, a farming industry trade group, recently built and funded an incubator in downtown Salinas to house and support two dozen ag-tech startups like HeavyConnect, which in turn have committed to hiring CSin3 graduates.

Bringing technology to agriculture

"We have three companies that are currently hiring, and their priority is to find local talent," says Lisa Dobbins, consulting manager of the Western Growers Center for Innovation & Technology. "The City of Salinas has really opened up and wanted to bridge Silicon Valley in terms of bringing ag and tech together."

In May, Constante was among the program's first class of graduates. She now has a full-time job with Seattle-based agriculture technology company iFood Decision Sciences.

"This program changed my life around," Constante says. "There's nothing out there [like it] in the whole of the United States. And it works."

That's what has other farming hubs watching, and thinking maybe they could do it too. Atallah says he's fielded calls from other cities and states about how to replicate the program's success.

"In reality, victory is one person at a time," Atallah says. "And eventually we'll succeed in moving the majority."

It's a bitter-sweet victory for Constante, knowing that her mom will still be out here in the fields, bending thousands of times even before she herself gets up for work.

"My dream is to have my parents retire from this," Constante says, looking across the strawberry fields at the distant workers bobbing up and down, their scarves whipping behind them in the wind.