Russian Meteor Blast Thrust Asteroid Danger into Spotlight 1 Year Ago Today

One year later, the impact of the surprise Russian meteor explosion is still being felt all over the world.

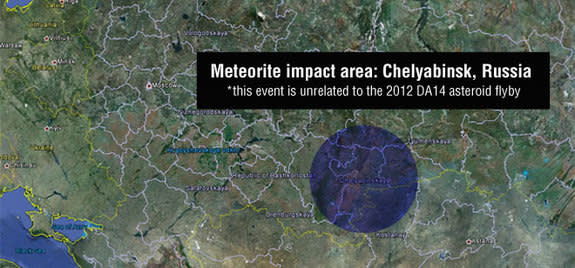

On Feb. 15, 2013, a 65-foot-wide (20 meters) asteroid detonated in the skies over the Russian city of Chelyabinsk, causing millions of dollars of damage and injuring 1,500 people. The dramatic event served as a wake-up call, many scientists say, alerting the world to the dangers posed by the millions of space rocks that reside in Earth's neck of the cosmic woods.

"These types of events are no longer hypothetical," David Kring, of the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston, said in December at the annual fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union (AGU) in San Francisco. "We've been up here talking about these types of things for years, but now the entire world understands that they can be real." [Photos: Russian Meteor Explosion of Feb. 15, 2013]

Caught off guard

The asteroid that caused the Russian fireball came streaking into Earth's atmosphere shortly after dawn one year ago today, exploding about 14 miles (23 kilometers) above the ground.

The blast generated a shock wave that hit the city of Chelyabinsk within a minute or two, breaking thousands of windows. (Shards of flying glass caused most of the injuries.)

Chelyabinsk "was the first asteroid-impact disaster in human history," Clark Chapman, of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colo., said at the December AGU meeting. "Nobody was killed, but nonetheless, the early estimates of the total damage of several tens of millions of dollars ranks it with a typical United States presidentially-declared major disaster."

Adding to the celestial drama, the Chelyabinsk impact occurred on the same day that a 100-foot-wide (30 m) space rock called 2012 DA14 cruised within 17,200 miles (27,000 km) of Earth, coming closer than many communications satellites circling our planet.

Scientists knew about 2012 DA14 and had predicted its close approach. But the Russian fireball caught everybody off-guard, as the asteroid that caused it had escaped detection until its dying day.

And there are plenty of other space rocks like the Chelyabinsk object out there, cruising unnamed and unknown through the dark depths of space. Indeed, scientists have catalogued just 10,600 near-Earth asteroids out of a total population believed to number in the millions.

For decades, researchers have been saying that they need more money and more instruments to start filling in the big gaps on the near-Earth asteroid map. And Chelyabinsk gave them a powerful example with which to augment their argument.

A lasting impact

The events of Feb. 15, 2013 got the attention of power brokers as well as the general public, said David Morrison of NASA's Ames Research Center and the SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) Institute.

"There was a planetary defense conference that was, by coincidence, scheduled for two months after Chelyabinsk," Morrison said during a public lecture in Silicon Valley in November. "We had had mostly geeky engineers and scientists at these conferences — until this one, when two high-ranking people from FEMA [the Federal Emergency Management Agency] came and spent the whole time there to begin to study what the civil-defense or disaster implications would be of impacts like this."

And a few weeks after the fireball, he added, the Russian and United States militaries began talking about how to work together to find and defend Earth against hazardous asteroids.

Further, the U.S. Congress held several hearings about planetary defense in the aftermath of Chelyabinsk, and the Obama adminstration asked Congress to double NASA's asteroid-hunting budget, to $40 million.

Finally, last June, NASA announced that it was launching an asteroid "Grand Challenge," which would solicit ideas from industry, academia and the general public about the best ways to detect potentially hazardous asteroids and prevent them from hitting Earth.

The extra attention could help new instruments such as the privately funded Sentinel Space Telescope get off the ground. The nonprofit B612 Foundation is developing the infrared Sentinel, which it plans to launch to a Venus-like orbit in 2018. From there, the scope should be able to spot 500,000 new asteroids in less than six years of operation, officials say.

"We have the technology to deflect asteroids, but we cannot do anything about the objects we don’t know exist," B612 Foundation chairman and CEO Ed Lu, a former NASA astronaut, wrote in a blog post shortly after Chelyabinsk.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Copyright 2014 SPACE.com, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.