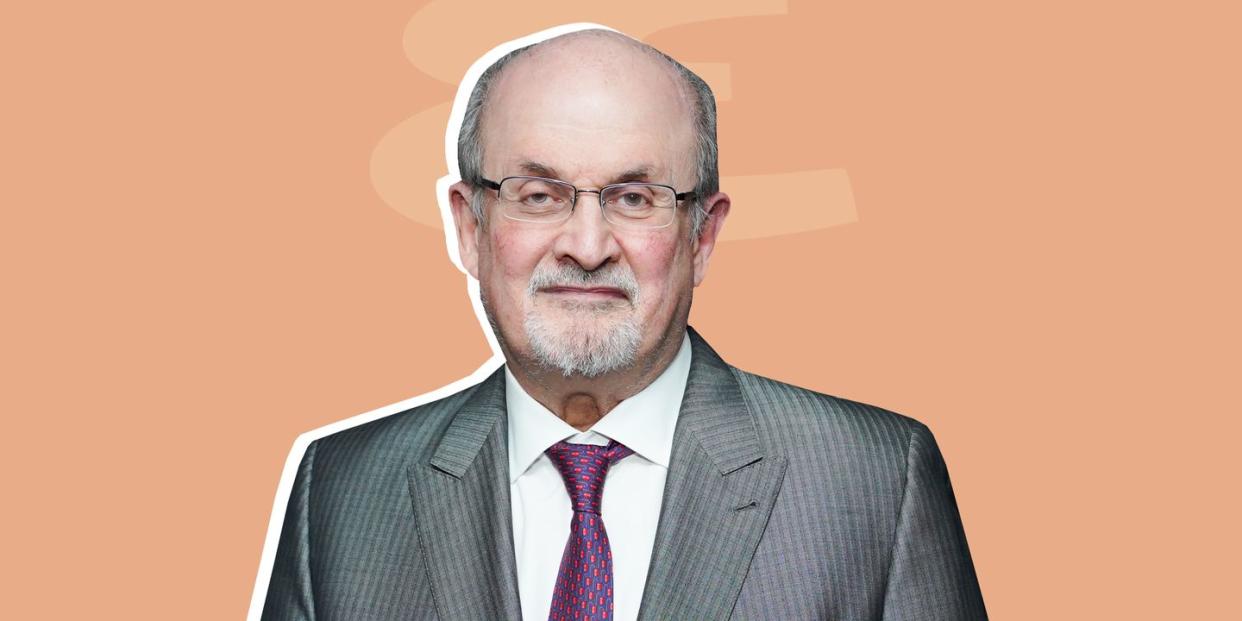

Salman Rushdie Makes a Triumphant Return to the Page

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

There is a confronting moment in Victory City, Salman Rushdie’s latest novel, when the nine-year-old heroine sees her mother walk into an inferno. After a devastating war kills the town’s menfolk, the women all decide to end their lives. Young Pampa Kampana can only watch in horror as she witnesses her mother’s gruesome death. Smelling “burning flesh in her nostrils,” Pampa decides then and there that she “would laugh at death and turn her face toward light.”

From the ashes of this blaze, she plants seeds. A literal city soon sprouts as if by magic. It’s filled with imposing palaces and grandiose temples. The people born into this landscape are given the actual memories Pampa has of her mother, ensuring these are never lost to time, but gifted and regifted for generations. When the world-building ends, “Victory City” and the Bisnaga Empire stand tall.

Victory City is Rushdie’s 15th novel, written before the violent 2022 stabbing that partially blinded him, and it will remind readers of his incredible imagination. Against his fictional city backdrop, the book sees Rushdie argue against the corrupting power held by religion while probing parallels between India’s past and present.

Even before the recent attack, Rushdie has long been targeted by violence. His 1988 novel, The Satanic Verses, enraged many Muslims around the world for its fictionalized depiction of the Islamic prophet, Muhammad. This outrage culminated in 1989 when Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa against Rushdie—or a call for Muslims to assassinate Rushdie. The novel itself has become an enduring symbol of Islamic blasphemy, with its notoriety now mostly superseding its content. (So much so that the criminal who stabbed Rushdie last year claimed to only have “read like two pages.”)

The new novel “translates” Pampa’s own verses chronicling the history of Victory City and her mother’s life. This manuscript is discovered some centuries later and retold to us by way of a sometimes wry translator (a Rushdie stand-in), who pieces the narrative together with sweeping editorial asides.

After her mother’s death, Pampa discovers that a goddess has vested her with incredible celestial powers. It’s when two roaming brother farmers arrive at the site of the ashes that she decides to plant the seeds that will build Victory City. (The city itself is based on the medieval Indian Kingdom of Vijayanagara, which rose and fell from 1336–1565.) While retelling Pampa’s redemptive life story, Rushdie fictionalizes Vijayanagara’s many wars and peacetimes, monarchs and regicides, colonial conquests and failed coups, all in the grand tradition of a Grecian epic. Sometimes the book reads like writing of other contemporary epic “translators”—in particular, Roberto Calasso and his work Ardor, which maps the mysticism and belief systems of northern India’s ancient Vedic people.

$24.99

amazon.com

Victory City is soon propelled forward as the seeds sprout a sprawling metropolis; then, one brother is crowned king and marries Pampa. Other nearby empires are aggressively colonized, with the city now a thriving, if sometimes politically fraught, feudal kingdom. While the two brothers vie for control and place, Pampa remains quietly steadfast in her cause, ensuring that women aren’t ever made to face prospects like her mother. However, politics and religious zealotry soon erode Pampa’s authority, forcing her into exile. She vows to return and restore equality to women that the city now denies.

Pampa herself is ageless, fated to outlive those around her for centuries because of her divinity. As the endless melt of time, war, and old age afflicts the brothers and her children (and their children and their children), she lives on. Her determination to memorialize the city’s origins and her feminist cause persists, too. Upon her return to the town some decades later, Pampa ensures that women are once again given education opportunities and training, access to skilled jobs like judges and bailiffs, and military prowess to battle wars better than their male peers. But these policies are abandoned once more when new leaders find themselves corrupted by religion and its views on women, and push Pampa out.

Rushdie’s epic tale plays out on a magical scale as sand walls emerge around the city and people morph into birds, all reminiscent of Ovid’s ancient Roman epic, Metamorphoses. Within the city, however, remain the evergreen conflicts of politics and religion, creation and destruction, feminist freedom over male chauvinism, all unfurling across the centuries.

It’s not difficult to see parallels with India today, especially as it pertains to religion’s recent weaponization in politics. Like Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his party’s aggressive Hindu nationalism politics, one Victory City king introduces a policy known as the “New Orthodox,” which declares that one true religion ranks above all others. The Bisnaga Empire sometimes registers not unlike its present day successor: “The world of faith had grown together too close to temporal power.”

This isn’t the first time Rushdie has wrestled with the antecedents of India’s history, either real or imagined. In Midnight’s Children, his Booker Prize-winning work, his protagonist’s life story mirrors India’s own, starting with the country’s declaration of independence in 1947. The novel embraced magic realism (a literary style that takes common or everyday experiences and reincarnates them as unreal or strange) to heighten the country’s fraught, and often checkered, lurch out from colonial rule.

The sheer surrealness of massive, seismic change within several decades—swinging from earnest democratic freedoms in the 1950s to authoritarian rule in the 1970s—is deftly captured in Midnight’s Children. The protagonist, Saleem, is born at midnight when India declares its independence from the Commonwealth, and thereby is gifted with special telepathic powers, suggestive of a newfound autonomous freedom. (Other children born at midnight can change sex, see through time, and even teleport.) These mind-reading abilities allow Saleem to loudly broadcast the novel’s key themes of creation and violence, fractured personal and national identity, and navigating chaos as a collective—as both a post-colonial Indian citizen and a nation. In the cacophony of voices grappling with such turmoil, we are told that memory unfortunately can be fleeting. India, in short, is “a nation of forgetters.”

$13.69

amazon.com

The novel’s magic realism—from the protagonist’s nose being shaped like a penis to a blind art lover—evokes the disorder many post-colonial countries experienced in the 20th century. Rushdie uses this style to pull readers forcefully into his fictional worlds. His other best-known works in this tradition include Shame and The Satanic Verses. The first sees Rushdie push hard on violence and metaphor, as he wrestles with the political and cultural health of Pakistan. The latter mines ideas of good versus evil and human nature. It’s this second book, however, that upended Rushdie’s life entirely, sending him underground for almost a decade.

The Satanic Verses is one big allegory. The story begins with two actors from India flying over the English Channel before their jet explodes from a hijacking bombing. A hallucinatory dream then begins for the pair, as they each miraculously survive the crash and land on a desolate beach—one with a white halo, the other with hooves and horns. You see where this is going. From there, readers get dreams within dreams, fantasies within fantasies, and characters melting into the margins, as a tale of biblical proportions is etched out.

Reading the novel is a truly surreal experience. The phantasmagorical parts ask us to imagine ourselves in divine bliss or hellish condemnation. The subplot involving a man named Mahound, which many readers at the time took as a thinly-veiled representation of the Prophet Muhammad, brought a kind of perverted magic realism to Rushdie’s own world. Indeed, the real and frightening sudden changes to Rushdie’s life—a deadly bounty being issued, protests in Pakistan killing people, the book disappearing from bookstores overnight—were eerily reminiscent of his own fiction’s disorder.

For Rushdie, surreal spectacles in stories ask readers to more deeply engage with the anarchy and outrageousness of the real events that sit behind them. Midnight’s Children retold Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s crackdown on civil liberties and the mass incarceration of people during a period known as “The Emergency,” from 1975-77. In the book, Prime Minister Gandhi sets her sights on the mass destruction of the midnight’s children through sterilization—a terrifying but true measure the real Gandhi adopted against citizens.

By contrast, Rushdie plays a game with readers of Shame, asking whether the setting is truly Pakistan in spite of telling us repeatedly that it’s “not quite Pakistan.” While it indisputably is Pakistan—with haunting depictions of the regimes of Prime Ministers Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and Muhammad Zia ul-Haq—Rushdie frequently gives us ironic disclaimers: “I am only telling a sort of modern fairy tale, so that’s all right; nobody need get upset, or take anything I say too seriously. No drastic action need be taken either.” These comments only serve to ignite our interest in the real-life events situated behind the book’s hypnotic fever dreams.

If themes like the dangers of religious extremism or prying open silent gaps in history drove Rushdie in earlier novels, they are once again on display in Victory City. So too is feminism.

With his retelling of the lost Vijayanagara Kingdom, we are challenged to expand our understanding of the subcontinent’s many fabled myths and metaphors—for these too are history, even if fictional. Rushdie tells us that there’s a joyous pleasure taking this route because it creates a wholly immersive experience, where mythical stories can reform our thinking of India and its rich cultural and political narratives. Where magic realism played a role in Rushdie’s previous fictions in highlighting the outrages of post-colonial India, Victory City embraces epic storytelling to give Western readers greater access to the country’s hidden histories, and to share inspired portraits of women sitting at history’s margins.

It’s this focus on India’s lores that breaks with Rushdie’s more recent writing tradition. Since his move to the U.S. some twenty years ago, he has largely set his books in America, writing with a keen and humorous lens on its politics and culture. There is his satirical take on Don Quixote, Quichotte, which records the exploits of a traveling pharmaceutical salesman obsessed with T.V. who falls for a small screen star. The novel touches on everything from the opioid crisis to screen addiction to climate change. The Golden House, set between the start of the Obama administration until present day, wrestles with the conflict between a single family and its patriarchal structures, asking whether one can truly become an American citizen today.

$14.79

amazon.com

Rushdie’s return to magic, myth, and India’s ancient stories is dazzling. With mercurial prose and vivid renderings, Rushdie never loses us in Victory City’s convolutions, but instead builds our trust to travail the many grand events of Pampa’s imagined empire. Whether his pieces all add up—like the changing rules of Pampa’s magical powers or crows parroting overheard conversations and context back to her—is ultimately beside the point. It’s her quiet and redeeming life, spent seeking respect and self-regard in all women, that is so restorative. And much like his other satirical writing, humor can sometimes help make such a point. For example, when Pampa asks that erotic art be displayed around the city to encourage more free-thinking and liberal behavior, she is rebuffed by the city’s priest, who reminds her that these are medieval times, not some freethinking future. Pampa retorts: “Let it be the 14th century everywhere else. It’s going to be the 15th century here.” The art is soon displayed.

As Pampa “whispers” to her city’s citizens—first giving them their memories and then later swaying their thoughts—Rushdie impresses upon readers the power of imaginative storytelling (“quiet whispering”). Taking threads of India today (such as corrupting religious zealotry) and some tendencies of ancient epic poetry (like grand battles and complex family dynasties), Rushdie returns to his talent for remaking India as an uncategorizable place that shows endless possibilities for cultural understanding.

Reading Victory City, one can’t help but feel that there is a quiet connection between Pampa and Rushdie. Works of great imagination—both Pampa’s epic narrative and Rushdie’s retelling of it—are powerful antidotes to the corrosion that politics and religion can reap together today, especially in India. At one point, a newly minted king of the city proclaims: “All false narratives will be suppressed.” Magical tales of talking crows and city-building seeds have the power to inspire the same emotions that religion and politics do, creating a comforting belief system and escape from the bleaker aspects of life. They also don’t usually lead to the same tragedies seen throughout human history, even if they are “false.”

Whether it’s an allegory for present-day India or a feminist retelling of a pre-colonial empire (or both!), Victory City nevertheless celebrates a singular story of female resilience. Once a young girl left a distraught witness to her mother’s death, Pampa forges a life rooted in hope and equality for herself and other women. It’s an empowering story that lives within and beyond Victory City, and spreads out ageless like Pampa herself. As Rushdie tell us, “Fictions could be as powerful as histories … allowing [people] to understand their own natures and the natures of those around them, and making them real.”

You Might Also Like