Sask. First Nation reinstates state of emergency in response to drug, gang activity after elders assaulted

Warning: This story contains distressing details.

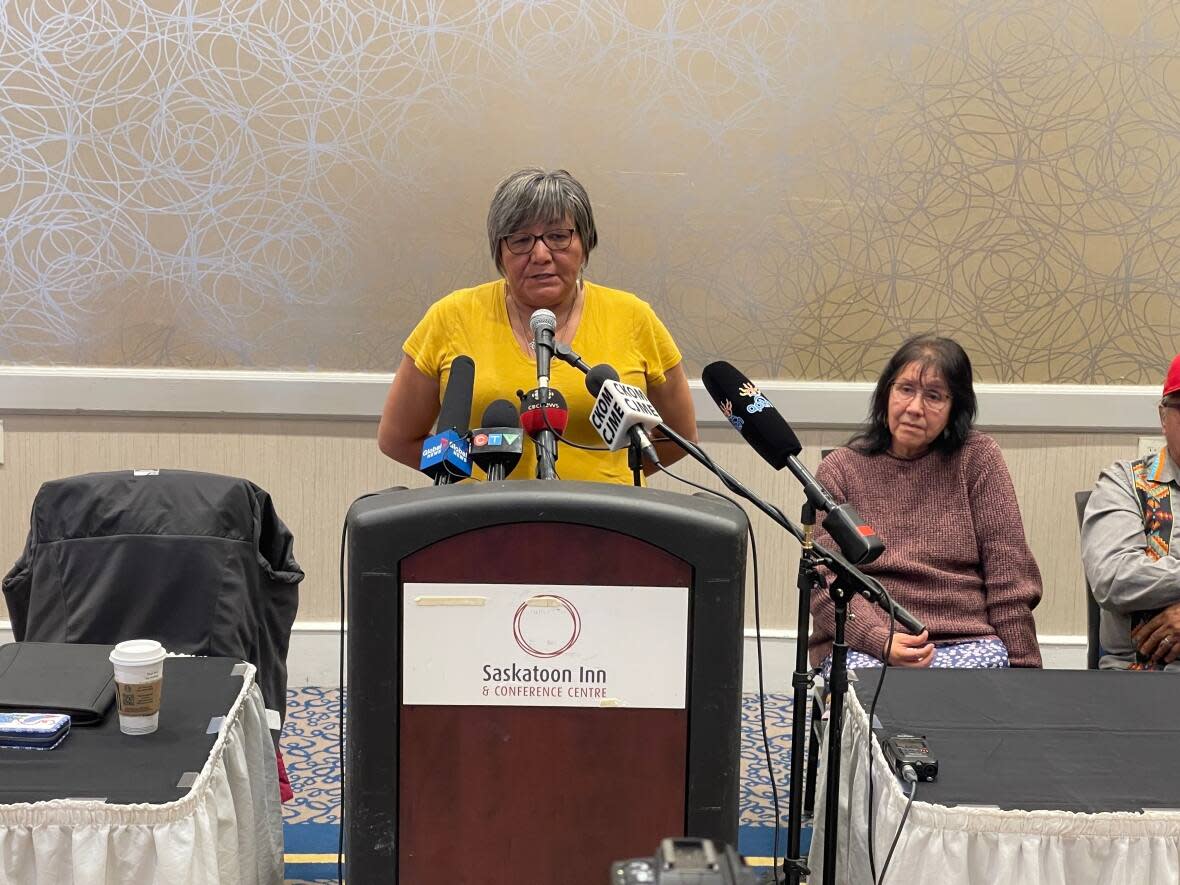

The chief of Buffalo River Dene Nation summarized the horrifying details of a weekend assault of an elder as she reinstated a state of emergency in the community and called for provincial and federal help on Wednesday.

The First Nation community of about 800 people in northwestern Saskatchewan had issued a state of emergency on June 3, 2022, in response to increased gang violence and drug activity.

Chief Norma Catarat reinstated that emergency declaration and asked for support for policing and mental health and addictions services in the First Nation, about 400 kilometres northwest of Prince Albert.

She said it doesn't have a treatment centre, detox centre or mental health unit.

The First Nation has mental health workers and workers through the National Native Alcohol and Drug Abuse Program, but those are "limited resources and they are overworked," Catarat said.

"We don't have the capacity in the community. People have to leave the community" for help, she said.

More immediately, she wants at least 20 additional security guards in the community and self-defence courses its members, especially for elders.

The security agency they're communicating with quoted them at $200,000 for three weeks of service, she said.

"The gangs and the drugs have come to a point in my community where my community is living in fear," Catarat said, adding that community members feel powerless.

She recounted a vicious assault on Friday night — one of two elder assaults this weekend, Catarat said — saying a woman kicked in the door of a woman's residence, pulled her from her bed by her hair and beat her.

The woman didn't even hear it coming because her hearing aids were out, Catarat said, and she was only rescued when the neighbours heard her screaming for help.

Catarat said the woman has bruised collarbones and two broken ribs, and is scared to return home, instead choosing to live with family out of province.

There are "gangs driving around with handguns, intimidating people; elders sitting at night with a gun loaded so their wife can sleep because their grandkids are affiliated with gangs," said Catarat.

"It is a crisis; it is an emergency. We need to do something now."

Lawrence Piche, an elder from the First Nation, said he's stood up against gang violence for years and said he's willing to put his life on the line to solve the issue.

"Those gangs out there … you're supposed to be warriors, your job is to help the elders and the people. I ask of you to take a serious look at yourself: where am I going, what am I doing?" he said.

"Take care of yourselves, because our lives depend on you."

Gangs, drugs treated as 'the norm': tribal chief

Tribal Chief Richard Ben with the Meadow Lake Tribal Council said First Nation communities need revamped justice systems to better address the issues, pointing to the recent stabbing tragedy at James Smith Cree Nation that left 10 people dead and 18 wounded, not counting the two men accused.

He echoed Catarat's observation that three gangs in the small community operate essentially unbridled, and suggested that if crime happens in a First Nations community it's out of sight and out of mind for others.

"No one says nothing, because it's normal … they're using our kids to sell their drugs and it's the norm, but we don't talk about it because it's on the reserve," he said.

Ben also called the issue of crystal meth in Indigenous communities an epidemic that is being swept under the rug.

"Why do our communities have to issue a state of emergency for us to be heard?" he said.

Community policing an essential service

Heather Bear, a vice-chief with the Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations, echoed a call made by Catarat and other First Nations community leaders for a local policing initiative, alongside calls for addictions and mental health support.

The Federation represents 74 First Nation communities in the province.

"Everyone should be able to feel safe whether they're in their home, whether they're on the street, whether they're at work," Bear said.

"Policing needs to be an essential service on every First Nation not only in this region but in this country."

Dutch Lerat, a vice-chief with the FSIN, holds the justice folder for the organization. He said there are RCMP detachments and peace officers on reserves.

Tribal councils and communities can hopefully build on that existing enforcement, Lerat said, calling for "policing in the community, for the community, by the community."

When Buffalo River initially declared a state of emergency in June, it had a task force enter the community for what Catarat called an "enforcement drive."

She said because of complicated governance and land ownership, the community can't enforce its own bylaws and doesn't have the capacity to do it on their own.

And the current system means that RCMP have to drive anywhere from two to six hours to bring detained suspects into holding cells, which means yanking resources from a community that needs them.

"The security services that we are looking into, it's going to cost us a lot of money, but it is something that we need to put in place now before I have to bury another member," Catarat said.