Saskatchewan's HIV rate highest in Canada, up 800% in 1 region

A year after Saskatchewan doctors called on the provincial government to declare a public health state of emergency over HIV and AIDS, the incidence of both are nearing an all-time high.

Dr. Kris Stewart, a physician in Saskatoon who is part of the Saskatchewan HIV Collaborative, said slight progress has been made, but he's not sure if it was a result of the request.

Government representatives have been meeting with the doctors regularly, he said, but funding hasn't increased. When inflation is accounted for, Stewart said, those in the field are actually dealing with a bit of a funding decrease.

According to Stewart, it has been determined that people with HIV who are receiving treatment do not transmit the disease, and therefore it's a good investment for the province. Despite this knowledge, he said, he still sees advanced infections resulting in death.

"Very often these are young people, their whole lives ahead of them," he said. "Sometimes they have children. In this time and place in the world, we should be doing better than this. And we're not."

According to a statement from the Ministry of Health, the province has provided $3.13 million since 2010 in support of HIV programs, and $9 million last year on medication for HIV patients.

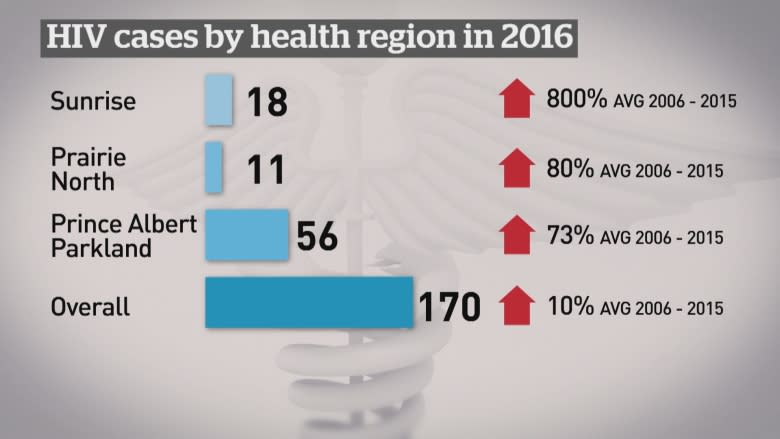

The number of new HIV cases in the province peaked in 2009 at 199. A preliminary report released this year by the government of Saskatchewan found that after decreasing for five consecutive years, the number of new cases in 2016 was back up to 170, an increase of six per cent over 2015.

Saskatchewan has the highest rates of HIV in Canada, with 2,091 cases reported between 1985 and 2016. The number of new cases in Saskatchewan is almost triple the national average, Stewart said.

"We're the only jurisdiction where the incidence has gone up recently. So that should be a cause for alarm," he said.

Only Regina and Saskatoon saw fewer new cases in 2016 than usual. HIV cases in the Prince Albert Parkland Health Region rose by 73 per cent and by 80 per cent in Prairie North.

Stewart said it's more difficult to lower the numbers now because the increases are being seen in more remote, northern areas, as opposed to the urban locations the HIV strategy has been implemented in.

According to the province's written statement, "work remains to make testing, services, and patient-centred care more accessible, especially in rural and remote areas."

The province is working with the Saskatchewan HIV Collaborative and HIV-positive patients to develop a three-year work plan.

The group, which also includes various health-care providers and health regions, will focus on education, collaboration between provincial and federal health systems, and addressing barriers to obtaining treatment. It will also attempt to close the gap in service provided to rural and urban communities.

3 southern First Nations face outbreak

Out of the 170 new cases of HIV in the province, 79 per cent self-identified as Indigenous.

The First Nations of Cote, Key and Keeseekoose, near Kamsack, Sask., are facing what's being classified as an HIV outbreak.

They fall into the Sunrise Health Region, which had an 800 per cent spike in HIV cases in 2016. From 2006 to 2015, there was an average of two new cases a year in the area. In 2016, 18 new cases were identified.

Dr. Ibrihim Khan, Health Canada's regional medical health officer responsible for Saskatchewan First Nations, said injection drug use is a major problem in the area and has been a driver of HIV infections, especially in local First Nations.

In Saskatchewan, 16 out of 100,000 people have HIV, according to Khan. Among residents of the three First Nations around Kamsak, there are 117 cases out of every 100,000 people.

Khan said Health Canada has been working with Sunrise Health Region, the province, local doctors, nurses and First Nations leadership in the area.

The community recently held three dedicated HIV testing sessions with nurses testing a record number of patients.

"The rates are alarming, but I think the leadership is doing an incredible job in terms of accepting the fact that it is a problem and doing something about it," Khan said.

There were 76,675 HIV tests in the province in 2016, the highest on record. Khan said this accounts for part of the increase in cases.

Khan said there are now 18 programs on Saskatchewan reserves addressing the disease, along with 13 mobile nursing teams and 25 HIV point-of-care testing sights. He said he wants to double those numbers in the next year.

Ted Quewezance is a former chief of Keeseekoose First Nation and a residential school survivor. He has been an advocate of a community-based approach to health care and the issues that have plagued Cote, Key, and Keeseekoose First Nations for years.

"It's a perpetual crisis in the quantity and quality of health care for band members," said Quewezance

"Existing services are really not culturally safe, and the status quo of the delivery of health care is really unacceptable to our three leaders."

Quewezance, like Khan, believes it's important to target the underlying issues that have led to the HIV outbreak. The people in his community are struggling with many other health issues, too.

"I truly believe the HIV issue in our community is not only HIV. It's our methadone issues, and we have the drug issues in the three communities."

Difficult access

Disparities in health care are also affecting the population negatively, according to Quewezance. He says it's part of what led to his son's death several years ago.

Many Indigenous people who live in First Nation communities are unable to easily access specialists and diagnostic and followup services.

"You go to the Royal University Hospital [in Saskatoon] and by the time you get there, it's way too late," said Quewezance.

New Beginnings Outreach Centre opened in Kamsack last fall, offering support for those living with HIV, addictions and mental health issues.

The three chiefs of Key, Cote, and Keeseekoose First Nations, along with health-care professionals and other leaders, like Quewezance, are working on the formation of a three-nation health authority.

Community solution needed

"Everybody waits for a crisis to happen. Now it's hitting the news. It's something our health teams identified, and it's late in the game, but in our perspective, we feel we can deal with it from a community perspective," said Quewezance.

"It's no sense bringing in people from the outside to fix our problems."

The group does not plan to wait for Health Canada or the province to answer its calls for more to be done, and is pursuing its own solution, based on "engagement, inclusion, and total involvement" of community members.

The leadership within the communities believe a united health authority would give them more power to help people in need within the community.

According to Quewezance, if government and Health Canada come on board, the future health authority plans to build a detox centre and palliative care facility to address some of the area's most pressing health-care issues.