How saying yes to free Wi-Fi could mean 'you are the product' for businesses

Twenty minutes after Zoe Elder stopped at a Gateway Newstands location in downtown Toronto to buy a pack of cigarettes, an email showed up in her personal Hotmail inbox.

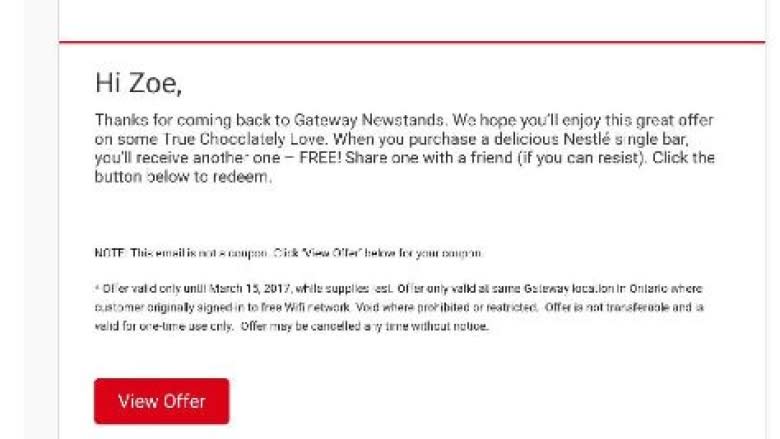

"Buy one Nestlé single bar + get one free," it began. The sender? Gateway Newstands.

Though Elder, 30, didn't know it at the time, she was being targeted by a Wi-Fi marketing campaign — anyone logged in to a store's free Wi-Fi is sent advertisements and promotions.

"I was completely floored. I didn't understand," said Elder. "I didn't know if it was a coincidence, or something I had signed up for … I was going through everything."

Turnstyle, the company that built the campaign that messaged Elder, said the emails are only sent if users first log in to Gateway's Wi-Fi, which then ends up giving over their email addresses. An email is sent that restates the users are giving their permission to get messages.

Elder said she doesn't remember signing onto anything, and she never received the first email from Gateway or Turnstyle.

"I actually feel like my phone got violated, to be honest," she said.

Bhupesh Shah, a professor of marketing and digital media at Seneca College, isn't surprised.

"If you went to the average person on the street, they probably wouldn't be aware that [Wi-Fi marketing] is happening," he told CBC Toronto.

That, said Shah, is going to change.

"As technology improves, it becomes easier to employ these technologies into retail," he said. "This is something that more and more retail organizations will use."

'If you're not paying for the product, you are the product'

Shah, Turnstyle and Gateway Newsstands couldn't explain what happened in Elder's case, arguing it's unlikely that the opt-in system could have such a serious glitch.

But Shah said it feeds into a bigger phenomenon: jumping on free Wi-Fi networks without realizing the possible implications.

Signing in using your Facebook log-in, phone number or email is akin to opening a possible floodgate, said Shah.

"You've in many cases allowed the organization to market to you, to collect your data," he said.

So how can you avoid being targeted?

Turnstyle vice-president Ryan Freeman told CBC Toronto that people receiving messages in a Turnstyle campaign are able to globally opt out of receiving any further advertising from any of his company's clients.

He said the first email is sent after log-in to ensure people know what they're signing up for.

But Shah argues that for many, little attention is paid to a Wi-Fi sign-in.

"I would say most people don't read the terms and conditions. If you want Wi-Fi, you want Wi-Fi — you really don't care," he said.

Shah has a favourite saying about social media:' "If you're not paying for the product, you are the product."

A push for millennial attention

Gateway Newstands president Noah Aychental told CBC Toronto that its three-month Wi-Fi marketing trial, undertaken with Nestlé as a partner, is specifically aimed at millennials.

"We have to speak to them where most of their communications are happening. They're not buying magazines, they're not reading newspapers," he said.

Though Aychental can't say if his company will expand the trial beyond its current 25 Greater Toronto Area stores, he is convinced it's a fair trade between business and consumer.

"The deal is that if you are near our store, there's free internet access," he said.

He was surprised to hear about Elder's negative reaction to the message, arguing that most people have experienced this kind of advertising.

"I think as a culture we are so engulfed in our media devices that it doesn't take much of an ask to invite someone to look at their phone for the 400,000th time that day," he said.

But Elder sees it differently.

"There's no way that everybody has [heard of it]. Because I am one of those people who never has," she said. "I understand this is the way marketing is going, but I do feel violated."