Scientists seek drug to ‘rewire’ adult brain after stroke

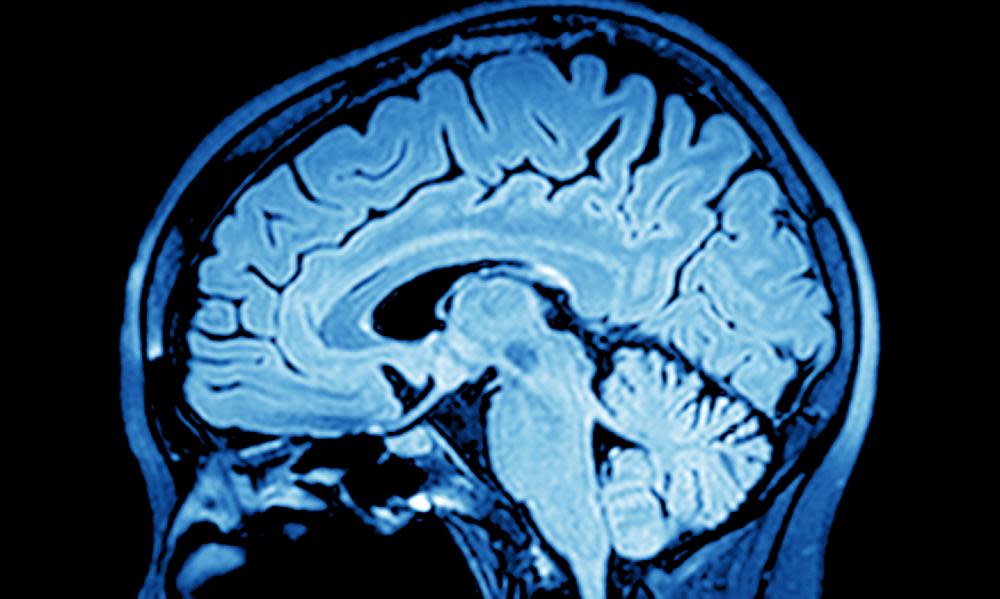

Photograph: akesak/Getty Images/iStockphoto

Adults who have experienced a stroke may one day be able to take a drug to help their brain “rewire” itself, so that tasks once carried out by now-damaged areas can be taken over by other regions, researchers have claimed.

The ability for the brain to rewire, so-called “brain plasticity”, is thought to occur throughout life; however, while children have a high degree of brain plasticity, adult brains are generally thought to be less plastic.

Research looking at children and young adults who had a stroke as a baby – a situation thought to affect at least one in 4,000 around the time of their birth – has highlighted the incredible ability of the young brain to rewire.

Elissa Newport, a professor of neurology at Georgetown University school of medicine in Washington DC, detailed a new study involving 12 such individuals, aged between 12 and 25.

“What you see is the right hemisphere, which is never in control of language in anyone who is healthy, is apparently capable of taking over language if you lose left hemisphere,” said Newport, who presented the findings at a meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Austin, Texas. “This does not happen in adults,” she added.

Using brain imaging the team found that the regions in the right hemisphere of the brain that took over were in the mirror image location to those used on the left side of the brain in healthy people. That, she said, emphasises that it is not just any area of the brain that takes over a function should a region become damaged.

Newport said that by understanding what underpins the brain plasticity seen in youngsters, scientists might be able to come up with ways to make the adult brain more plastic, potentially offering hope to adults who have had a stroke.

While less of a priority, the same kind of mechanisms that might help reorganise language areas in those who have had a stroke could work in healthy people to help them learn a second language, Newport admitted.

Takao Hensch, a professor of molecular and cell biology at Harvard University, who was also speaking at the meeting, said that his research in mice showed that by blocking certain molecules in the adult brain that hinder plasticity, it was possible to increase its ability to rewire.

“The baseline of the brain is plastic, to rewire itself. Through evolution it is necessary to layer on brake-like factors to prevent too much rewiring from happening after a certain point,” he said. “This offers novel therapeutic possibilities. If we could judiciously lift the brakes later in life perhaps we could reopen this window.”

Hensch is already working on possible therapeutics. He said that among the possibilities, drugs routinely used for mood disorders might show potential to increase plasticity in adults. His previous research has shown that adults given the drug valproate, used to treat bipolar disorder, regain the ability to learn perfect pitch – a skill that is usually only seen in children who began studying music before the age of six.

But he said there was cause for caution when it came to tinkering with the ability for the brain to change. “We have to consider though that the brain is well formed by then [adulthood] and has passed through its own critical period. The starting point is quite different,” he said. “We worry a lot about translating these results to humans. What would it mean to reopen the critical period a second time? Would we be wiping out your identity, who you’d become through all those years of development?”

But Nick Ward, a professor of clinical neurology and neurorehabilitation at University College London, said that it was not the case that adults recovering from a stroke could not use other parts of their brain to take over tasks. “Relatively well-recovered adult stroke patients tend to have different activity patterns compared with healthy people. Other parts of the language network might be used to support language recovery,” he said.

Ward also noted that it is thought, from animal models, that the stroke itself can increase brain plasticity in adults for a few months, meaning that timely rehabilitation and training are key.

“Drugs that keep the window open longer or reopen it would be good too,” said Ward. “It’s just that at the moment, services are being slashed and so the ‘dose’ of rehab is so low, no drug is going to help – doubling the effect of not very much rehab still gives you not very much rehab.”