Scotland's drug death crisis needs a radical harm reduction response – now

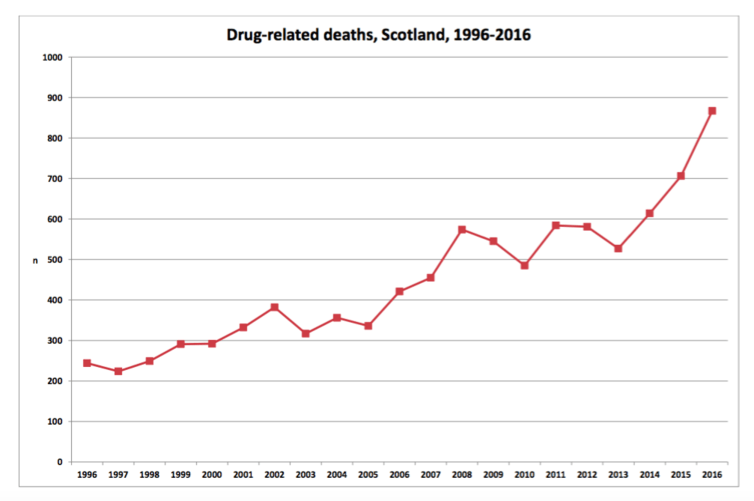

The newly published figures of annual drug-related deaths (DRD) in Scotland are appalling. The National Records of Scotland figure of 867 represents the highest annual total recorded – a 23% increase on the previous year, and a 100% increase since 421 Scottish DRDs were reported in 2006.

The recent annual figures for England and Wales covering the same period also reported a record high figure of 3,744 deaths, representing a 2% increase on the previous year.

This makes the Scottish figures even more concerning: it is estimated that the Scottish DRD rate is now 2.5 times that of elsewhere in the UK, and among the highest in Europe. Drug use has been recently confirmed as a leading cause of early death in Scotland, ahead of chronic liver diseases and colorectal cancer.

Root causes

An ageing cohort of polydrug users (those who use a combination of drugs), the availability of increasingly strong and diverse street drugs, cuts in drug treatment budgets, and wider economic austerity, all create a perfect storm for such a crisis.

The roots of the situation seem to be historic and intertwined with pervasive social inequalities. New research on DRD has described a “cohort effect” for those born between 1960 and 1980, especially among men living in the most deprived areas in Scotland. The researchers conclude that “exposure to the changing social, economic and political contexts of the 1980s created a delayed negative health impact”.

Recent research on the needs of older drug users in Scotland found a group experiencing some of the most extreme health inequalities seen in Scottish society today. In addition to poor physical health, persistent and enduring mental health problems were common, exacerbated by loneliness, isolation, homelessness and stigma. It is not only older drug users who are affected, however: over a quarter (28%) of all deaths in 2016 involved those aged under 35.

Although dramatic changes in the age profile of DRDs have been observed, the make up of DRD in Scotland has not changed much in 20 years in terms of the drugs used. The substantial rise in the number of DRDs is not driven by Fentanyl use, as seen in North America’s opioid crisis, nor is it due to the adverse effect of the UK Psychoactive Substance Act which, in the banning of “legal highs”, is believed to push some users towards more dangerous substances.

New drugs and behaviours come and go and influence the mortality data to varying extents but the main problem and cause of death in Scotland remains opioids, consistently involved in around 90% of cases and increasingly in combination with benzodiazepines (sleeping pills and anxiety medication). Encouraging people out of opioid substitution treatment (OST) prematurely can increase the risk of relapse and overdose.

How to respond

Scotland’s Minister for Public Health and Sport, Aileen Campbell, recently announced a “refresh” of the national drugs strategy. Given the scale of the increase in DRDs since it was launched in 2008, the need for the refreshed strategy to be firmly evidence-based, with a measurable framework of actions, is of utmost importance.

In 2016, the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD) published a report on reducing opioid-related deaths in the UK. The report was largely ignored in the drugs strategy published in July by the UK government whose focus has switched from harm reduction to abstinence and recovery.

However, the ACMD report did make a number of recommendations that are within the gift of the Scottish government, including: continued investment in high-quality OST of optimal dosage and duration; provision of heroin-assisted treatment for patients for whom other forms of OST have not been effective; availability of the opioid antagonist Naloxone to people who use opioids, their families and friends; and provision of medically supervised drug consumption clinics in localities with a high concentration of injecting drug use. All these interventions are also recommended in the recently published UK treatment guidelines for drug misuse and dependence.

Making progress

It is essential to also recognise the progress that has been achieved in Scotland. The national naloxone programme was the first of its kind internationally and has been endorsed by the World Health Organisation. Evaluation of its impact concluded that it has had a significant effect in reducing opioid-related deaths following release from prison, a period of elevated DRD risk. Without this, the latest DRD figures may well have been even higher.

Glasgow’s council and health officials have now approved the establishment of the UK’s first safer drug consumption facility and a heroin-assisted treatment service. This development was largely in response to an ongoing outbreak of HIV in the city, but also aims to respond to increasing drug-related mortality within this vulnerable population.

Less impressive is Scotland’s treatment record. Treatment is a known protective factor against DRD yet too few of the country’s 61,500 problem drug users are engaged in treatment and, critically, retention rates are poor, particularly in comparison to countries like Norway, which have achieved a turnaround in DRD rates over the past five years.

What next?

Reiterating the conclusions of both the ACMD report and Scotland’s Independent Expert Review on OST, integrated services are needed across health and social care that are well tailored to each person. These should help them to achieve wider recovery outcomes, including those focused on general health and well-being. The new UK treatment guidelines should also be at the heart of achieving this ambition and improving the quality and effectiveness of Scotland’s treatment landscape.

The prevention of DRDs in Scotland requires an immediate and radical harm reduction led response, developed in collaboration with people who use drugs. Evidence-based solutions are available, but it is absolutely crucial that they receive support from all sections of Scottish society in order to destigmatise drug use and encourage people to seek help.

The tragedy of Scotland’s spiralling deaths from drug use is everyone’s problem. The time for brave leadership and concerted action is now.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Andrew McAuley has previously received research funding from the Scottish Government and the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA). Andrew is a current member of the Scottish Government Partnership for Action on Drugs (PADS) Harms group and co-chair of the Sexual Health and Blood-Borne Virus Framework Prevention Leads group. The authors would like to thank David Liddell, CEO of the Scottish Drugs Forum, and Dr Saket Priyadarshi, Honorary Clinical Senior Lecturer at the University of Glasgow, for their advice in the preparation of this article.

Grants for drug related and HIV/AIDS research over three decades from Medical Research Council, the Royal College of General Practitioners and the Scottish Chief Scientist Office. Chair of the Harms Group of the Scottish Government advisory committees.

Tessa Parkes works as Research Director for the Salvation Army-funded Centre for Addiction Services and Research at the University of Stirling. She has received funding from the Scottish Government, NHS Health Scotland, the British Academy and the Economic and Social Research Council. She is a member of the Partnership for Action on Drugs in Scotland (PADS) Executive group, and of a SIGN Guideline group on foetal alcohol spectrum disorder. She is contributing to this article as an academic researcher, not as a member of any particular group. Her views are her own informed by the research she has done over the past twenty years.