How Seasonal Affective Disorder can impact your mental health

“Life starts all over again when it gets crisp in the fall,” wrote F Scott Fitzgerald in The Great Gatsby, using the American term for autumn, which has for centuries occupied the minds of poets and novelists as a time of renewal and new beginnings. But for Luke Evans, a 28-year-old photographer from London, this time of year signals something much darker. He is one of around 30 per cent of the population who is thought to suffer in some way from Seasonal Affective Disorder, a form of depression that comes and goes in seasonal patterns, bringing low mood, irritability, and lethargy.

In the winter months, Evans becomes deeply fatigued, and his mood shoots down. “Episodes when I’m feeling down are definitely a lot more frequent throughout the darker seasons,” he says. “I think my lowest point throughout the year is always within winter.”

But this week, a group of Dutch scientists threw doubt over whether the condition really exists. The study at the University of Groningen tracked more than 5,000 people, each of whom were asked about their moods at different points in the year. The vast majority of participants showed no decline in their mood at the end of summer. The small number who did become more gloomy already displayed high levels of neuroticism – the tendency to experience negative emotions in response to stress.

“The findings of this study do not support the widespread belief that seasons influence mood to a great extent,” the researchers said in the journal, Plos One. Wim Winthorst, the lead author, suggested that people who believe they suffer from SAD “might have the tendency to attribute their negative moods to factors beyond their individual control”.

Another study in 2016, which tracked the moods of more than 34,000 American adults, concluded that SAD is probably a myth. “The belief in the association of seasonal changes with depression is more-or-less taken as a given, and the same belief is widespread in our culture,” said Dr Steven LoBello, a professor of psychology at Auburn University, Alabama, at the time. “We analysed the data from many angles and found that the prevalence of depression is very stable across different latitudes, seasons of the year, and sunlight exposures.”

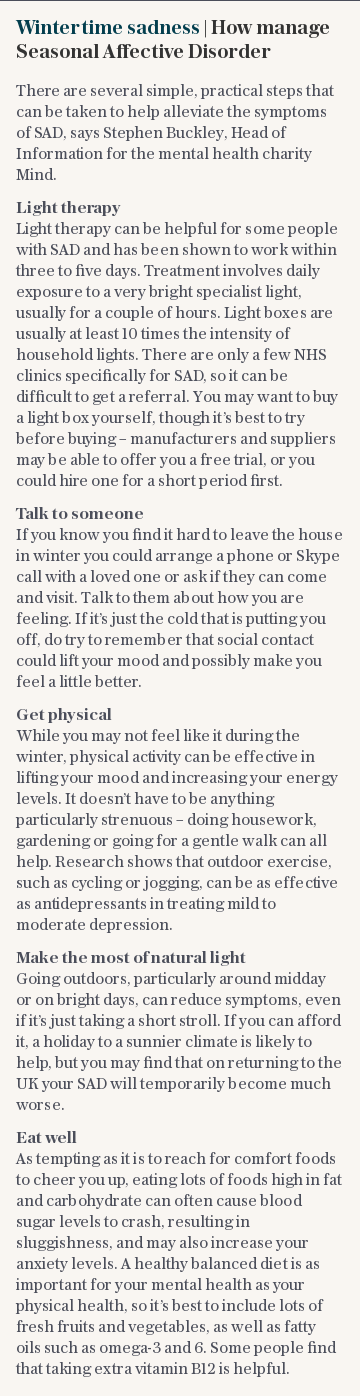

The NHS has recognised SAD as a medical condition since the Nineties and, since then, doctors have seen an explosion in the number of people who believe they suffer from it. To receive a diagnosis, patients must exhibit major depressive symptoms which coincide with specific seasons – for example, they feel unusually low in winter and autumn, and much happier in spring and summer. For treatments, doctors now commonly recommend light boxes, including the popular ‘SAD lamp’, which produces a light with a very high lux; and even Cognitive Behavioural Therapy.

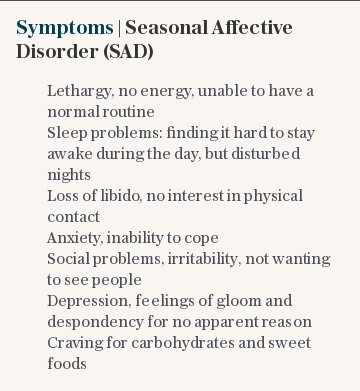

This week’s University of Groningen findings are bound to prove controversial among some therapists, many of whom are convinced that their patients exhibit a clear change in mood in the winter months that cannot be explained by other factors. Lindsay George, a counsellor and psychotherapist, says that severe fatigue is a key symptom that separates SAD from simply feeling a bit glum about the weather. “While winter blues often involves a lack of sleep, SAD will likely leave you feeling fatigued and lethargic, and getting out of bed and starting the day can be extremely difficult,” she says. “All of these symptoms can vary in severity, and if untreated, can have a significant impact on your overall health and ability to carry out day-to-day activities.”

Dr Guy Meadows, founder of The Sleep School, says sleep could well be a key factor. “Winter brings shorter days, meaning we all experience less sunlight,” he told the Telegraph in 2017. “Sunlight helps inform the brain when to wake up, as well as boosting our morning alertness levels. Since most of us have to get up for work before the sun rises, this can leave us in a state of sleep inertia (that groggy morning feeling) for longer.”

The findings are also likely to be challenged by SAD sufferers themselves, many of whom claim to identify a clear link between sunlight exposure and their mental health. Monty Don, the host of BBC Two’s Gardeners World, has written movingly about his own battles with depression and SAD, and said he struggles to lift his head from the pillow on the very darkest winter mornings. “Between the end of February and the beginning of October I have no desire to move my home at all,” he told the Telegraph in an interview last year. “But I’d love to spend November, December, January, and maybe February, somewhere where the sun shone.”

Luke Evans was diagnosed with the condition about eight years ago when the therapist he was seeing to treat his anxiety suggested he might also suffer from SAD. He admits that the medical definition of SAD is fairly “fluffy”, but thinks it accurately describes his experience. “I'm quite susceptible to changes in light and how they feel. It's not like in the summer, everything's great and then suddenly as soon as the clocks turn back, everything's bad. It's a lot more subtle. But it's definitely noticeable, it changes seasonally for sure. For friends who’ve had it, it’s a lot more black and white.”

People who doubt the existence of SAD often say that it probably has more to do with fresh air than sunlight: it is proven that going outside benefits our mental health, and people are simply more likely to choose to venture outside in the summer. Night-time wintry walks would do a good job of dispelling the SAD blues, the theory goes – we just don’t like them. But Evans says that he hates the heat in summer and possesses an unusual love of cold, dark walks, and so actually spends far more time outside in the winter months.

Evans was prescribed light therapy, which does a very effective job of buoying his moods – another reason why he thinks that sunlight, rather than outdoor time other factors, is the key to his winter depression. He wakes up with a dawn-simulating alarm clock, which gradually lights up his bedroom over half an hour. Then, he answers emails at his desk under the glow of his SAD lamp, a nifty device which instantly leaves him “uplifted”.

“It might be a placebo, but if it's a placebo and it works, then it's equally as valid.”