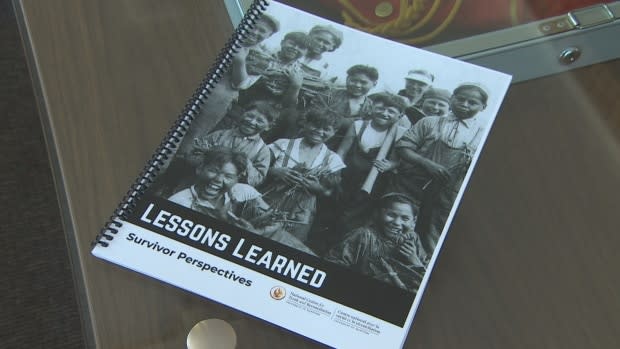

Settlement process retraumatizes some residential school survivors, report says

Some survivors of the residential school system say they felt frustrated and retraumatized by the bureaucratic nature of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement (IRSSA) process, a report released this week says.

Survivors who spoke with the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, which led the review and produced the report, said while they felt their stories were finally heard, they often felt "shuffled through the process," said Ry Moran, the centre's director.

The centre spoke with over 300 people for the report, which describes how survivors had to repeatedly recount traumatic experiences in order to complete the settlement claim process.

"The compensation was awarded only upon sufficient 'evidence,' which often required precise and in-depth disclosure," the report said.

Terri Brown, who is chair of the centre's survivors circle and chief of Tahltan First Nation in British Columbia, said she had a horrible experience with the settlement process, where her claim was ultimately rejected. She never wants to go through it again, she said.

She said when she was putting together her application, she tried to get a lawyer to help her, but he wouldn't take on her case because she didn't have any documentation to support her allegation.

"He said because I didn't speak to anybody about this issue at the school that my claim wouldn't have any strength and he wouldn't take my claim," she said.

"Who would I tell? I was 10 years old ... I didn't even know what was happening was actually wrong."

She felt the process was more about "making money off of our misery" than trying to help those traumatized by the residential school system.

Another survivor, Eugene Arcand, a Cree from Muskeg Lake First Nation in Saskatchewan, said it was a painful process for him, and painful to watch other survivors go through it as well.

"For me, the invasiveness, persistence and depth of the questioning we were subjected to inside of our compensation hearings was obscene and did not need to occur to verify whether sexual or physical abuse had occurred," he said in a message preceding the report. "That day of my hearing, and the days that followed, were some of the worst days in my life, second only to when my abuse actually occurred."

The implementation of the IRSSA began in 2007, after the federal government, churches and former students reached a $2-billion settlement over abuses inflicted at residential schools.

Aside from payments to survivors, it also resulted in funds for healing programs and the creation of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

Lack of cultural sensitivity

In some cases, the retraumatization triggered alcohol abuse in some survivors, or even suicide, the report said.

Of particular concern, the report said, is survivors' accounts of feeling as though they were doubted by lawyers, judges or government officials about the abuse they suffered.

One survivor stated they felt they were "brushed off," the report said.

"This was a process that was supposed to give survivors the benefit of the doubt and provide compensation for the serious sexual and physical abuse that they had suffered."

Another significant challenge the report revealed was the lack of understanding or sensitivity toward Indigenous culture in what ended up being a highly litigious, bureaucratic process, Moran said.

The report recommended that government officials, adjudicators, judges and legal counsel involved in these types of claims in the future should be required to go through cultural competency training "and carry out their duties in a non-discriminatory manner."

"Training of non-Indigenous professionals is needed in advance of the process," the report said.

"Further, there should be concerted efforts to involve Indigenous professionals who are more likely to possess culturally competent skills. Cultural safety is not optional."

Despite these challenges, survivors found the independent Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC), which was a result of the IRSSA, helped them heal by sharing their experiences.

"The fact that the TRC was a result of the survivors' settlement of the largest class-action suit in Canada was a positive element in this regard."

The report also noted the positive impacts the settlements had on some survivors who received them. One homeless survivor used her payment to buy a home and then host community events such as workshops, drum groups, talking circles and sweat lodges.

"Survivors clearly expressed that monetary compensation was never their first priority. However, compensation represented an acknowledgement of the harm and of the federal government accountability for that harm," the report said.

In an emailed statement, a spokesperson for the office of the minister of Crown-Indigenous relations said it welcomes the report because it "sheds light on areas of improvement" for future settlement processes. The statement indicates the government is already incorporating survivors' views when it comes to implementing the commission's calls to action.

For example, current settlement agreements will be adopting streamlined, paper-based claims processes intended to minimize retraumatization and the government will be ensuring legal fees are not deducted from payments to survivors and their families, according to the minister's office.