‘My sister wasn’t killed by a serial killer’: The Rillington Place murders’ final twist

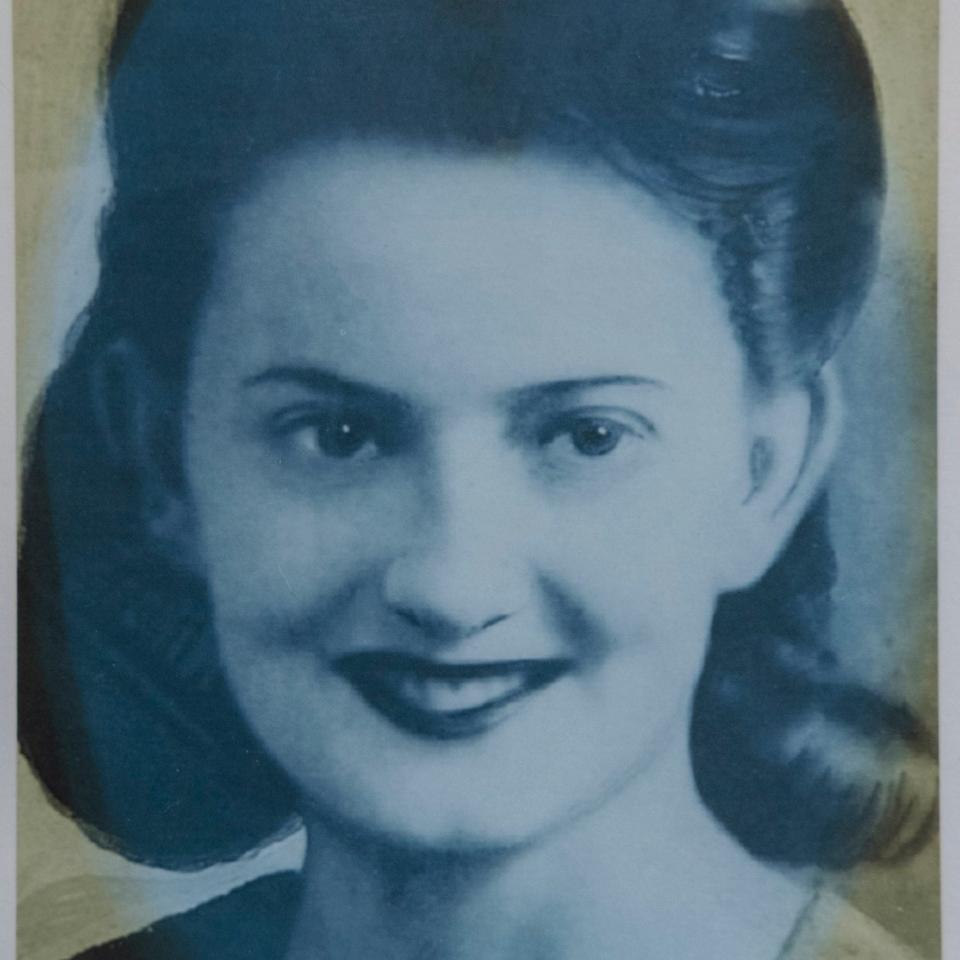

Peter Thorley is a man of routine. Every morning, when the 85 year-old wakes up at home in Arundel, West Sussex, he looks at the grainy photograph of his older sister, Beryl, beside his bed. Then he goes downstairs and scours the pages of Radio Times for any programmes that might depict her murder for entertainment.

They’re easy to find: he only need look for the words “Rillington Place”. He draws a line through any such programme in black pen, and vows to avoid the TV that night. He doesn’t need reminding of what happened in November 1949. For more than 70 years, he’s thought of little else.

“Every day,” he says. “And it’s done a lot of damage to my life, I can tell you that.”

The story of 10 Rillington Place, and the murders committed there, has captivated the British public like few cases in history. Books, documentaries and podcasts have been dedicated to picking apart its gruesome details, as well as two acclaimed dramatic adaptations – a 1971 film starring Richard Attenborough and John Hurt, and a 2016 BBC miniseries, with Tim Roth and Samantha Morton.

“Neither is very good, there are five mistakes in the first scene of that Attenborough film alone…” Thorley says.

Both deal with an established sequence of events: in the spring of 1948, Beryl and her husband, Timothy Evans, moved into the top flat of 10 Rillington Place in Notting Hill, London. On the ground floor lived John ‘Reg’ Christie and his wife, Ethel. In October of that year, Beryl gave birth to a daughter, Geraldine, but the marriage was unhappy – Evans was a drunk and a gambler, who was physically and verbally abusive to his wife.

Eighteen months after the couple moved in, Evans reported to police that his wife was dead and he had “disposed” of her. Officers searched the house but found nothing, then returned a second time and discovered the body of Beryl, who was only 20, wrapped in a tablecloth in the back garden wash-house, with 12-month-old Geraldine alongside her. Both had been strangled.

Evans was sent to the gallows in March 1950. But that wasn’t it: three years later, it was discovered that Christie, their quiet neighbour, was in fact a serial killer who had murdered at least six women, including his wife, at 10 Rillington Place throughout the 40s and early 50s, hiding their bodies on the premises.

It wasn’t long before some suggested that it must surely have been the monster downstairs who killed Beryl and Geraldine. Campaigns were launched, principally by Evans’s family, to recognise what they said was a gross miscarriage of justice. Eventually, he received a posthumous royal pardon. And that, so far as most people believe, was the end of that.

But not for Peter Thorley or his wife of 55 years, Lea. In their opinion, the truth has never fully been heard.

“The film, the books, they’ve clouded everybody’s judgement,” Lea says, sitting beside Thorley in their garden. “There has only ever been that one version of events. Nobody approached Peter’s family.” Thorley nods. “You would have thought she was an orphan.”

Thorley has now decided to get his side of the story out there, and in doing so delivers another twist in the saga. His new book, Inside 10 Rillington Place, argues that there was no miscarriage of justice at all.

“Evans killed my sister and little Geraldine,” he says. “I’m probably the only person left alive who was ever inside that house [the street has since been demolished and renamed] and knew these characters – Evans, Christie, Beryl. The people who’ve made those films don’t know what they’re talking about.”

One of four siblings (another brother and sister have since passed away), Thorley adored Beryl, who was six years older, and the pair were inseparable growing up in London. Shortly after meeting Evans on a blind date, she introduced him to her younger brother.

“He was a nasty piece of work, I never liked him. Drunken, mouthy, bad-tempered… I didn’t see what she saw in him,” says Thorley.

When Beryl and Evans moved into Rillington Place, Thorley – then only 13 – would visit. He’d be let in by Reg Christie, the unassuming, smartly-dressed man on the ground floor. They’d share tea and iced buns, and play snap. Thorley even sat in the chair in which Christie gassed and strangled many of his victims, before sexually assaulting them.

“He was always so nice to me. He never said a wrong word, we got on so well. I couldn’t believe it when they said he was a murderer,” he says. “He wouldn’t have left a child without a mother, and he would never have killed Geraldine. Christie wasn’t like that.”

Shortly before Beryl died, she told Thorley how scared she was of Evans, and gave him her wedding ring for safekeeping, believing her husband would pawn it. He still has it now. She also told him Evans had threatened to kill her.

Teenage Thorley was en route to New Zealand when the murders took place. His father, encouraged by a new wife who didn’t want the children around, had arranged for him to take up a place on a child emigration scheme. He arrived on a farm north of Auckland to a letter from his father, explaining, in heartbreakingly vague terms, “I want you to be a man like your Dad, as I have some very bad news for you.” He had left it to the farmer and his wife to actually explain what had happened.

“I knew there and then what I know now. It was him, Evans. I knew his temper, and I knew he’d told Beryl he was going to do it. There was never any doubt in my mind.”

By the time Thorley returned, Evans was a condemned man. In the ensuing years, as Christie’s killing spree was revealed and Beryl’s death became public property, he felt powerless to stop the narrative.

Thorley, who has investigated the crime with Lea for the past 35 years, argues that Christie knew Evans had killed Beryl and Geraldine and helped him to hide the bodies, but never turned him in because he had his own secrets in the house.

When Christie was caught, Thorley says, his defence team were quick to suggest he killed Beryl and Geraldine as a higher body count helped in their attempt to plead insanity. A convenient timeline the public could digest, police mistakes, and a successful campaign by the journalist Ludovic Kennedy – who used the case as a central plank in his efforts to abolish the death penalty – all contributed to a pardoning that he believes should never have been given.

Yet Thorley does not seek any official recognition of this version of events. What is done, he says, is done. The only thing he asks is that Beryl and Geraldine’s bodies be exhumed from the Catholic cemetery in London where they lie, to be reburied in Sussex.

“I want her here, next to me when I go,” he explains. “But this book is the final chapter. This is it now. This is what I know happened.”

Inside 10 Rillington Place by Peter Thorley available to buy now for £8.99 at books.telegraph.co.uk or call 0844 871 1514