Small town Alberta grateful for lenient COVID restrictions, anxious for economic recovery

Theo Springer says one of the benefits of having his women's clothing store in small town Alberta is that not everyone has to wear a mask when they walk into his store. Most of his customers do, but it's not mandatory.

Mask use in public places is voluntary in Didsbury, which lies halfway between Calgary and Red Deer and is home to 5,300 people. That's due in part because the number of COVID-19 infections in the rural community remains relatively low.

It's an almost unthinkable option for people who live in Alberta's large urban centres — or any other province in Canada — where health orders require people to wear masks to slow the spread of the coronavirus.

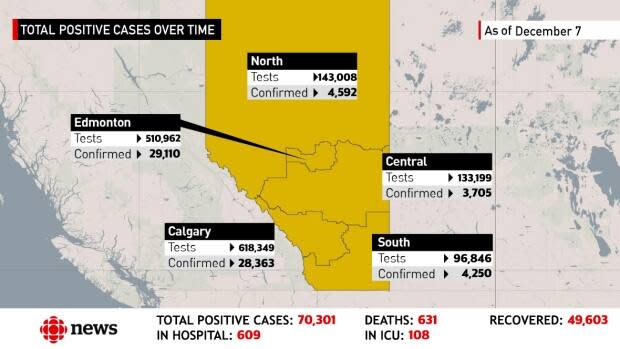

Albertans face different rules and restrictions depending on where they live, even though case numbers have been climbing at a record pace — and creeping up even in rural Alberta.

Didsbury is in Mountain View County, which has a population of almost 23,000 and only 27 active cases. The area has been moving in and out of enhanced public health measures as the case numbers rise and fall below the threshold of 100 cases per 100,000 people to trigger those extra measures. The rate currently sits at 118. By comparison, the rate in Calgary is 473.

Alberta remains the only province without a mandatory mask mandate.

It's been up to local municipalities and counties to decide their own rules and restrictions. Last week, Lethbridge County, for example, imposed a temporary mandatory face covering bylaw for all indoor public places. Offenders could face a $100 fine.

Springer says if anyone walks into his store and is wearing a mask, he and his staff will slip theirs on without hesitation.

Premier Jason Kenney has resisted a provincewide mask mandate, partly because he believes people outside the big cities would defy it.

He told United Conservative Party members last month that such a mandate would create a backlash in rural Alberta and that people would take them off the minute the government told them to wear one.

"Why would we do something that becomes counterproductive?"

"I just think we need to exercise just a bit of common sense in this," the premier said during a Facebook Live discussion on Nov. 20.

Springer isn't so sure about a backlash in rural Alberta. But he acknowledges not everyone supports wearing masks regardless of whether they live in urban or rural areas.

"We had one or two people in that said, 'I don't wear a mask,'" he said.

He says it can be difficult to convince someone who lives alone or within a small family cohort on a farm in a remote area to put on a mask because the risk of contracting the virus appears to be low.

"They would … defy that because they don't have the interaction, the close interactions on a daily basis like city folks," said Springer.

Springer and his wife, who are both Calgarians, purchased the store in 2017 and make the hour-long commute to their shop every day.

It has been a very challenging year for them. Just when the spring and summer merchandise arrived, the store was forced to close for two months. When it reopened, he had to offer the clothing at reduced prices. He applied for and received a $40,000 federal support loan.

The key right now is to remain open and avoid another lockdown — which, he says, could shutter his store permanently.

Response praised

The mayor of Didsbury says that while the government took heat for locking down small businesses in the spring and allowing big box retailers to remain open, tempers have cooled somewhat now that shop owners have been allowed to stay open during the second wave of the pandemic.

"It was a very gracious gesture of the premier to apologize for that lockdown of our small businesses and it was very gracious for small businesses to accept his apology," said Mayor Rhonda Hunter.

She says small business operators are more likely to provide a safer shopping experience by maintaining smaller customer counts and cleaner spaces than larger stores and malls — regardless of whether masks are mandatory.

She agrees with the premier that people are more likely to comply with mask wearing as long as it's a voluntary measure.

"People respect that, rather than have the government say you have to do that," she said.

"Keeping your freedom of choices and your liberties is really important," said Hunter, who points out there are just over two dozen cases in an area that covers almost 4,000 square kilometres.

Mask mandate up to the province, not the town

A town councillor brought forward a motion to discuss a local mandatory mask bylaw last month, but it was withdrawn after council said such a decision should be made by province.

"There's just no will to implement that on our people and on our citizens and businesses," said Hunter.

And there is no will to wade into such a contentious issue.

"I do absolutely believe there'd be pushback," she said.

Hunter isn't so sure the UCP government is avoiding a mandatory mask mandate because it could threaten the support it has in rural Alberta.

"The big votership of the UCP in our rural areas, that's, you know, without a doubt."

"But at the same time, you just have to look at the [COVID-19] numbers and I think they speak for themselves," said Hunter.

Local businesses decide

The sign on the door at the Renaissance Bakery and Café tells customers that mask use inside is mandatory. While there has been some pushback, most customers follow the rules.

"We get people that come in here and see that you need masks, 'oh, I'm not coming in,'" said owner Deborah Solda.

Solda says she admires Kenney for allowing businesses to stay open — and in rural Alberta, allowing businesses to decide whether their customers should wear a mask.

"He's allowed us to think for ourselves and say, 'Hey, how are we going to be able to continue through this?'"

"His mandate is making sure all Albertans are safe, and yet our economy is safe as well. So I think it's a very hard decision to make one way or the other."

Focus on economic recovery

While Solda's restaurant has seen fewer customers during the pandemic, her wholesale business — which sells cakes, Italian pastries and pasta to other businesses and cafes — is expanding.

"It is very positive, we actually haven't stopped working since COVID first hit us," said Solda.

But she doubts her business could survive another full lockdown.

"If we have to shut down again right now, all of us are going to be finished," she said.

Springer is hoping for a turnaround at his family-run business as well. He'd like people to consider local businesses first before big box and online retailers.

"We need support. We'd like to be here. We're happy to be here, that's what we want to do," he said.

Struggles continue

The community faces a number of economic hurdles, and supporting local businesses is one of them.

Construction, health care, social services, retail, transportation and warehousing rank as the top employment sectors, but fewer people are working, costs are rising and government support doesn't cover all of their expenses.

A soup kitchen that's run every Thursday night out of the town's historic former train station is seeing more people line up for a hot meal and donated food.

"We've seen a huge influx of seniors in need, we've seen a lot of families in need," said Sheree Andrews, president of Essentials for our Community, the group that runs the program.

Andrews says she was shocked to see so many seniors seeking help. She says many are on fixed incomes and have been unable to keep up with rising food prices.

She says more families are struggling because government support payments aren't enough to cover costs.

"We have seen so many families that are strong, stable members of our community, we've known for years that have worked, that are suddenly not working, and they're mortified that they have to come in and get help," she said.

Early on during the pandemic, the group received a government grant that provided 350 meals a week for those in need. However, that funding has come to an end.

"We are in need of more grant money. We are in need of more support."

"Definitely this will run out very quickly," she said.

Bryan Labby is an enterprise reporter with CBC Calgary. If you have a good story idea or tip, you can reach him at bryan.labby@cbc.ca or on Twitter at @CBCBryan.