Son who lost both parents to COVID-19 joins class action suit against Quebec nursing homes

Ian Peres said he didn't know what to do when his father told him he'd been left alone in his room for two days, in a dirty diaper, with no food or water, after being tested for COVID-19 in April.

"It was one of the scariest moments of my life," said Peres, who lives in Toronto.

He'd never heard his father so upset. The normally calm 86-year-old was so rattled, Peres and his brothers were worried he was going to have a heart attack.

"He was completely unravelled, insisting he wanted to be euthanized, and for Mommy to be euthanized," said Peres. "He kept saying he didn't want to live like this."

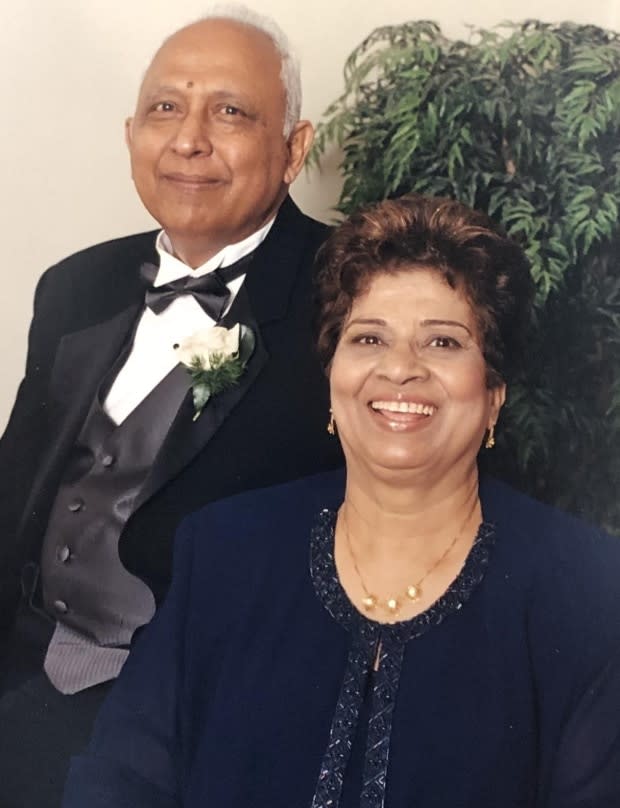

Peres's father, Frank, and his 84-year-old mother, Doris, lived at Centre d'Hébergement de Lachine. With families barred from visiting, neither Ian Peres nor his two brothers, who live in Montreal, could go to the long-term care home to console their father and to find out what was going on.

"It was hell," said Peres.

No chance to say goodbye

Frank Peres's COVID test came back negative.

But Doris tested positive. She died on April 23.

Their rooms were just the length of the corridor apart, but isolated from one another since the start of the pandemic, Frank never got the chance to see his wife of nearly 60 years and say goodbye.

"He cried bitterly when she died," said Peres.

Ian and his brothers discussed pulling their dad out of the care home immediately, but they were worried he would lose his spot if they later brought him back to the institution.

Frank Peres tested negative four times before his — and his children's — worst fear came true in mid-May.

"When he was diagnosed, he had absolute fear in his eyes," said Ian Peres.

He still can't believe his father became infected after being isolated in his room for two months. He questions the safety protocols the nursing home had in place and doesn't understand why front-line workers continued to move from home to home.

"Someone brought the infection into his room," he said.

Six days after the positive test result, Frank Peres died at the Jewish General Hospital.

His family has signed on to a class action lawsuit against Quebec's network of public long-term care homes, known by their French initials as CHSLDs, to shine a light on how badly they feel the system is failing seniors.

Suit amended to include COVID-19 victims

Lawyer Philippe Larochelle said the Peres family is looking for accountability for what happened to their parents and so many others in their situation.

Nearly two-thirds of the 4,713 Quebecers who have died from complications of COVID-19 were residents of long-term care homes.

Larochelle believes the high rate of infection and deaths from COVID-19 in those CHSLDs are a direct result of the conditions that were in place before the pandemic.

"I think it's coming to light in a more vivid way now with the COVID crisis," said Larochelle.

The $500-million class action lawsuit filed by Larochelle's firm, authorized last fall, contends the living conditions at CHSLDs are unacceptable, with poor food, low standards of hygiene, a lack of quality care and poor building maintenance.

In May, after the advent of the pandemic, the lawsuit was amended, with a request to add compensation for damages suffered due to COVID-19 outbreaks.

If it is authorized, the amendment will include three new subgroups: any resident who lived in a CHSLD with at least one positive COVID-19 case, any resident who contracted the virus, and the relatives or heirs of any resident who died from complications of the coronavirus.

Shortcomings before the pandemic

Peres said his family is not looking for a financial windfall, but he hopes the lawsuit will lead to much-needed reform.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, Peres said the Lachine home struggled with staffing shortages, especially on weekends.

He said on average, there was one patient attendant for every 30 residents, many of whom required significant care.

"My father would regularly complain about new nurses, virtually every single day," said Peres. "How can one have a baseline for patient care if you don't even understand who they are?"

Peres and his family often witnessed his parents' calls for assistance go unanswered, sometimes for hours, due to chronic short-staffing.

At the time that Doris Peres was admitted to the Lachine facility, in April 2018, she was still able to walk with the help of a walker, to get in and out of bed by herself and use the washroom, her son says.

But within six months, she was in diapers and had gained 25 pounds, which Peres blames on a lack of exercise and physiotherapy, and a poor diet.

"Within 12 months, she was bedridden and paralyzed with fear about moving," said Peres.

Her immobility and the lack of stimulation seriously affected her quality of life.

"She couldn't get up by herself. She had to be hoisted in the wheelchair. She was wheeled to the front of the elevators, and she was left there the entire day facing the wall," said Peres. "That was her last six months."

If she wanted to have a bowel movement, she was forced to go to the bathroom at a prescribed time each day — 4 p.m. If she couldn't wait, she had to go in her diaper.

Peres said the wait caused her to suffer from heart palpitations, sweats and severe cramping. If she did soil herself, Peres said, it would take orderlies a long time to get around to changing her, leading to frequent urinary tract infections.

During her final days, Peres said, his mother was not able to drink water due to her falling oxygen saturation levels.

She was put on oxygen, but she was severely dehydrated.

When Peres asked about hydration, he was stunned to learn the institution was not equipped to put her on an intravenous drip.

"It was almost five days my mother did not have one drop of water before she passed. I can only imagine she suffered some massive organ failure as a result," said Peres.

Poorly equipped to handle crisis

When the pandemic hit, Peres said, his family was not able to get any information from the Lachine home about whether it was secluding COVID-positive residents. The staff were equally tight-lipped about how many people were infected or who had died, he said.

"My dad told us there were several people infected on his wing," said Peres.

According to the lawsuit, by May 1, 65 residents of Centre d'Hébergement de Lachine were infected. That is more than one-third of the institution's residents.

Peres believes the province failed to provide long-term care homes with adequate protective gear, enough staffing, proper training or protocols to reduce viral transmission.

He said every Canadian should be concerned about what seniors were subjected to in these homes.

"In 10, 20, 30 years, this is us," he said.

Neither the Quebec Ministry of Health nor the regional health agency for the West Island, which operates the Lachine centre, would comment on the Peres family's case, due to the class action lawsuit.

Peres believes his parents deserved to be in a place that valued their quality of life. He's convinced his father, who had no major underlying health issues, would have lived another five or 10 years had he not contracted COVID-19.

"When we did our due diligence, this particular institution had better reviews in terms of care, he says. "But if this was better, we just dread what the other institutions were like that we did not select."