'It's special to me': Northern Peninsula residents rally behind rare char population

Every generation of Arctic char in Parker's River starts out in an environment with threats from human activity and, increasingly, climate change. But unlike many populations facing habitat changes and an uncertain future, the Arctic char running to and from Pistolet Bay, at the tip of Newfoundland's Northern Peninsula, are getting a little help along the way.

These fish are the most southerly of the diadromous — meaning they migrate between fresh and salt water — Arctic char (Salvelinus alpinus) in eastern North America. Suited to cold, Northern waters, Arctic char have been found as far south as Maine, but the fish farther to the south remain in freshwater and landlocked in lakes and tend to be smaller.

The novelty of the Parker's River Arctic char, being a population just on the edge of the subarctic region and estimated at fewer than 300 fish, has long been noted by locals from communities like Cook's Harbour, Raleigh, and even farther, from Pistolet Bay in St. Lunaire and St. Anthony, N.L.

Years of grassroots public awareness and conservation efforts in the area have been focused at the essential spawning river. It all started with a Save Our Char Action Committee, drawing in researchers and partner organizations, with activities culminating late in the fall in a significant river restoration project.

The work in 2021 involved, among other things, the dredging of silt from a pool that had started to fill in near the mouth of Parker's River and installation of natural overhangs to give shade and shelter in places where fish might pause in their migrations. The pieces were all designed by scientists and engineers to ease specific environmental pressures and aid both the char and other large finfish. The physical work, post-engineering and consultation, was estimated at about $200,000.

For future generations

Ralph Hedderson is the unofficial mayor of a group of 68 or so cabins not too far from the river. He collects the annual fee from property owners to keep up the road there.

Hedderson wasn't around or involved in the local Save Our Char Committee when it formed in 1982 but has been an enthusiastic participant in the more recent public education and conservation work. He walked the riverbanks to aid the pre-construction studies by expert consultants, even helping to post the final signage on the completed work in early December. He also works seasonally as a river guardian for the Department of Fisheries and Oceans.

Hedderson's taken in plenty of fish tales from Pistolet Bay, with its 26 regulated species of fish, and marvels at the fact the area doesn't get more attention. "This bay, this whole bay is like a little sanctuary," he said. At the same time, he has a special reverence for the Arctic char and their preferred river.

He said people will still make trips to the banks to watch some of the salmon and char and at least one spot along the river's edge has long been a popular gathering place, where family picnics were a common sight for many years.

"It's, ah … how do I say it? It's special to me," he said. "It's something that's in the neck of our woods and we don't want it destroyed. I've got two daughters myself and they've got kids coming up to see it."

The tip of the peninsula is popular with recreational anglers, and locals will sometimes try for a fish from the shore of the open bay. However, Hedderson said, there is generally buy-in all around on protection of the Parker's River char, while a ban on fishing at the river's mouth has long been in place. Rather than poaching, the concern right now is long-term environmental conditions and habitat.

"There's quite a few different threats there," said Chelsea Boaler, a PhD candidate and senior specialist with World Wildlife Fund Canada. Boaler was a lead hand on the completed river restoration project, officially a partnership of the grassroots Save Our Char Committee, St. Anthony Basin Resources Inc. — known as SABRI — the Atlantic Salmon Conservation Foundation, the WWF and DFO.

Boaler, who was at the river recently for all the final checks of the recent work and end signage, explained potential threats to the char come from things like forecast warming of local waters. There is risk from more frequent, intense rain leading to flooding that can carry and build up sediment and debris more quickly, making it more difficult for the fish to navigate and survive in the rivers. And while professional surveys found only a few signs of human incursions like ATV crossings along the river, preservation of the char population requires ongoing education and outreach.

Boaler said the specific activities in the recent restoration project came out of public consultations, including a virtual community information session and workshop held in October 2020, over a year ahead of the physical work at site. They were, in turn, built on partner input and recommendations from a habitat assessment report from a team of scientists and engineers with U.S.-based consultant Interfluve, which has qualifications fluvial geomorphology and overall expertise in waterbody interventions.

The up-front data collection involved expected things like water level checks, temperature loggers and drone surveys, to what might be unexpected, including measurements to provide a better understanding of the material type and size making up the riverbed and gravel shoals of the river. That material — say, silt versus gravel or pebbles — can matter greatly to a female char looking for just the right place to, every year or two, create a proper a spawning nest.

Biologist and PhD candidate Victoria Neville took part in the community consultations on the latest project and spent time helping the Interfluve team as part of her work with WWF, before she started a new position with DFO. She's been involved at the river this year, completing additional, independent data collection for DFO, to build on the earlier work.

"Rivers are constantly changing beings. They're not static. They grow, they change, they move," she said. The data collected this year, she explained, focused on habitat conditions upstream, including water temperature, quality and the presence of benthic invertebrates — food for growing char.

"I think the big reason we're doing all of this is these char are incredibly ecologically important, and basically you don't want to miss out on something. It's such an awesome phenomenon, such an incredible fish, a beautiful, rare and a unique fish for this area," she said.

Early study

The area's original Save Our Char Committee, formed in the 1980s, went dormant after years of activity but was revived when people noticed a drop in the local char population, around 2005-07. Its efforts drew the attention of environmental agencies and researchers.

It's the subsequent scientific study paired with local knowledge and observations that, over the years, has shaped the overall understanding of the area's rare char population. Per a WWF summary of studies through the years, one project, a partnership of the SOCC and biologists working with the Community-University Research for Recovery Alliance (an agency that wrapped up activities in 2014), in collaboration with DFO, involved completed surveys of about 50 recreational anglers active in the area and requested anglers submit the heads of any char they caught.

As the heads rolled in, mass spectrometry on the otoliths — ear stones — of the char revealed chemical signatures confirming time spent by each fish in both fresh and salt water, proof of their unique status among more southerly char populations.

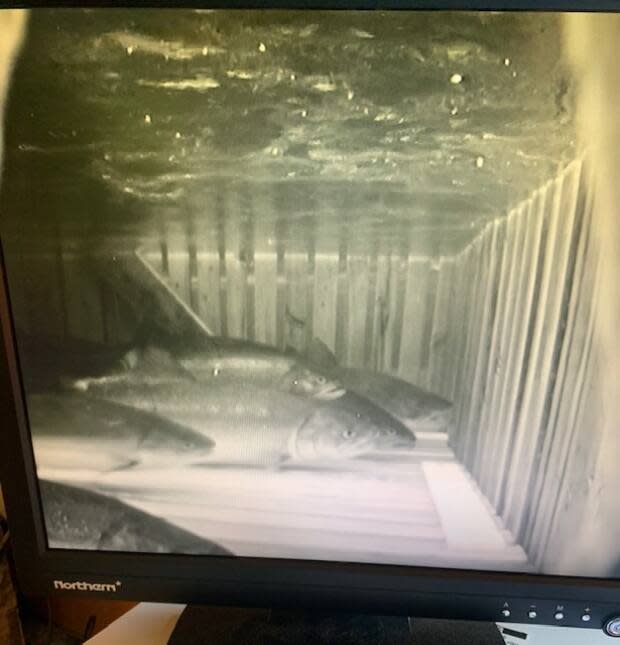

Between 2009 and 2011, thanks to the SOCC, the use of a counting fence and underwater camera pinned the number of char in Parker's Brook for the first time in modern memory at just under 300 fish, with other large finfish also present in the river (an additional roughly 200 Atlantic salmon and 200 brook trout in the same period).

The char will typically not migrate until they're a few years old and don't run nearly as far out into the Atlantic Ocean, or spend multiple years at sea, as Atlantic salmon can. Instead, they stay close to their home of Pistolet Bay, some even remaining just in the bay, making it a truly local population.

In 2012-13, DFO research scientist Corey Morris completed a tagging project involving both the local Arctic char and salmon. A separate bathymetric survey found particularly deep reaches, as deep as 33 metres, in a freshwater lake on the river system called Stock Pond, closer to the river's headwaters. It's believed depths like these, unusual compared with other systems in the area, may be a key feature in attracting char to run up Parker's River rather than elsewhere in the area.

Atop the historical work, the latest studies and actions were prompted by a trio of die-offs in 2012, 2015 and 2017 involving an estimated 100 char and about 70 salmon, with some additional, scattered fish found dead along the river in other years. A working theory that could account for at least some of the losses is that the fish were killed by the temperatures in the brackish waters near the river's mouth where silt had made the key pool too shallow, or certainly far shallower than years past.

Looking ahead

SABRI executive director Sam Elliott said his organization contributed to the latest project because of the potential for improved understanding and what he considers possible longer-term regional benefit through education.

"I looked at it from the perspective that there's potential here for this to be a research project for PhD students and probably somebody in their wisdom someday down the road might turn this into an educational component for students in the schools, where they would take some breed brood stock from the brook [Parker's River] and get some brood from them and then restock the brook and let them monitor it," he said.

"You might get some biologists coming out of the school systems thinking about the little project they were a part of when they were in the school system."

But the next step for all is simply a fresh, official count on the Arctic char population. Funding for a counting fence (it's a community project separate from DFO's regularly monitored rivers) ran dry after 2011, and while a fence was installed as part of the project this year, a particularly heavy dump of rain and flooding washed out the installation partway through the count. Boaler said she is working on applications now and know others have been working on everything needed to try again in 2022.

Looking long term, Neville says there are a few different, possible futures for the char of Pistolet Bay. Conservation efforts could allow the population to continue as is for many years. The population also might eventually become landlocked, adapting and remaining in the Parker's River system and not heading to sea. On the other hand, if conditions change enough or competing species move in, aided by the changing environment, or there is suddenly heavy poaching in the area, the char could disappear altogether.

Regardless, she believes it was, to date, the local effort that has given the population a little breathing room.

"There's no way that this project I think could occur without the high level of community engagement and champions within the community for this population of fish," she said. "People who realize its importance and continue to focus on it, they're really key."