How Super PACs Took Over The 2020 Democratic Primary

LAS VEGAS ― The unified front the 2020 Democratic presidential candidates once held against super PACs has totally crumbled, with every major non-billionaire candidate remaining in the race accepting the help of an outside group that can collect donations of any size.

At the start of the race last spring, basically every candidate in the field swore they did not want help from super PACs, which can accept and spend unlimited sums as long as they don’t directly coordinate with a candidate. The field, led by Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), argued super PACs were part of a corrupt campaign finance system that allowed the rich to exercise undue influence over politicians and policymaking, and that disavowing them would show voters they were serious about reform. It marked a major break from the crowded 2016 Republican primary, where nonprofit groups and super PACs bankrolled by the wealthy dominated the airwaves.

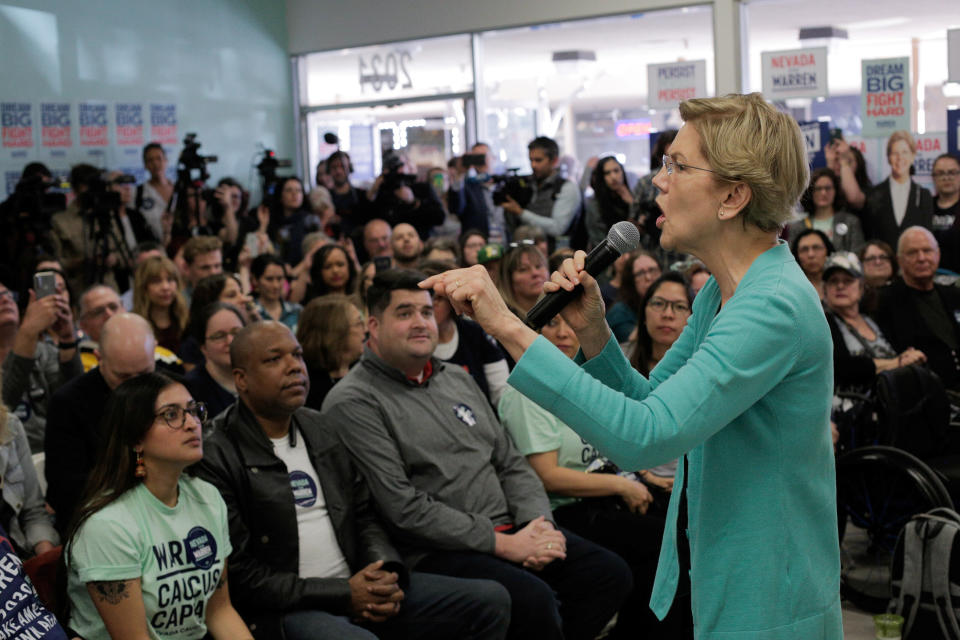

“We reached the point a few weeks ago where all of the men who were on the debate stage all had either super PACs or were multibillionaires who could rummage around in their sock drawers and find enough money to fund a campaign,” Warren told reporters after a canvass kickoff here on Thursday morning, when she declined to ask a newly formed super PAC supporting her to stand down. “If all the candidates want to get rid of super PACs, count me in. I’ll lead the charge. But that’s how it has to be. It can’t be the case that a bunch of people keep them and only one or two don’t.”

Warren’s reversal is the most dramatic because her promise to reform the nation’s campaign finance system is at the core of her candidacy. But it also marks the culmination of a field-wide flip-flop on outside groups spending big money. A progressive veterans’ group has already spent millions backing former South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigieg; former Vice President Joe Biden reversed course and endorsed a super PAC in the fall; and a constellation of progressive outside groups, including Our Revolution, which allows for unlimited anonymous donations, is backing Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.). Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.) got a super PAC not long before one popped up to support Warren.

The only candidates competing to challenge President Donald Trump not on that list are businessman Tom Steyer and former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, two billionaires who have combined to spend hundreds of millions of dollars of their own fortunes on running.

The slow-motion collapse of the field’s stance against super PAC has culminated just as the race is set to quickly get more expensive: In less than two weeks, the candidates will need to compete in 11 states on Super Tuesday, including California and Texas, two states with multiple expensive media markets. But it has multiple causes, including the emergence of two free-spending billionaires and the lack of political penalties for candidates who embraced super PACs.

“It was clear from the beginning that Democrats were going to need to use super PACs to defeat Donald Trump in the general election, and setting up an arbitrary ban on super PACs in the primary didn’t do anybody any good,” said Jared Leopold, a Democratic strategist. “The system sucks, but those are the rules.”

Leopold has a reason to dislike the ban. He worked for Washington Gov. Jay Inslee, who was the only candidate to embrace a super PAC at the beginning of the campaign. The group, called Act Now on Climate, raised and spent over $2 million on television ads and email gathering efforts to boost Inslee.

Progressive groups, led by End Citizens United, released multiple statements criticizing Inslee for embracing the group and issued an open letter calling on all the campaigns to disavow super PACs backing a single candidate. At the time, campaign finance advocates believed they had the upper hand politically, and most Democrats agreed. Shortly before the race began, Robby Mook ― who managed Hillary Clinton’s campaign in 2016 ― told The New York Times that super PACs would be a “liability as much as a strength” for campaigns.

Of all the candidates, Warren was the most aggressive in swearing off super PACs. From her very first campaign stop in Iowa in early January 2020, she laid down a marker and called for all the candidates to swear off super PACs. End Citizens United and other groups backed her up, and with the exception of Inslee, the candidates followed suit.

The first cracks started to appear in October, when Biden, who once said “people can’t possibly trust you” if you accept support from a big-money group, flip-flopped and blessed the creation of a super PAC backing him. Not long after, a super PAC supporting Sen. Cory Booker (D-N.J.) began airing ads. One emerged to support Sen. Kamala Harris (D-Calif.) the same day she dropped out of the race in early December, the day before VoteVets, a veterans’ group with an affiliated super PAC, announced its endorsement of Buttigieg. In January, a coalition of progressive groups, including some that accept unlimited and anonymous donations, announced they were partnering to support Sanders. Even entrepreneur Andrew Yang accepted a super PAC’s support.

(Though candidates legally have no ability to stop a super PAC from forming or paying for supportive advertising, an outright disavowal typically makes it difficult tor an outside group to raise substantial sums.)

None of the candidates faced real political penalties for accepting super PAC backing. Sanders and Warren attacked Biden but did not mount a sustained assault. While Warren mentioned the lack of super PAC support for her and Klobuchar at the Feb. 7 debate in New Hampshire, her campaign message had generally moved elsewhere. This lack of political pain, along with Bloomberg’s and Steyer’s billions in spending, left most of the candidates feeling they had no choice but to accept big money help to compete.

And the campaigns’ collective decision to set aside the rules from the early months of the primaries has operatives who worked for candidates who ran out of cash seething.

“Demagoguing super PACs and suggesting essentially that support from them makes you nefarious was a misguided waste of time, especially in a primary where two billionaires were demonstrating an unfettered willingness to spend whatever it takes to win,” said Ian Sams, a Democratic strategist who had worked for Harris’s campaign. “All Democrats want to get rid of dark money, but we have to win to reform campaign finance. Everyone is realizing that in order to do that, we need a shit ton of money.”

End Citizens United claimed success for keeping super PACs away from the primary for as long as they did. The group noted that outside groups backing Republicans had spent $193 million by the day of the New Hampshire primary in 2016, compared with just $15 million by Democratic groups in 2020. The lack of outside groups also kept the campaign from becoming negative ― candidates are often reluctant to air attack ads with their own names attached.

“We’re proud that a grassroots coalition of organizations and rank-and-file Democrats were able to hold back the big money for as long as we did,” said Patrick Burgwinkle, a spokesman for the group. “We’re very disappointed that single-candidate super PACs have forced their way into this Democratic primary and believe they should shut down. We’ve said from the beginning that the Democratic nominee should be chosen by the people, not big money.

“The biggest challenge campaigns have faced in this primary is generating authentic grassroots support, and if that’s the question your campaign is facing, then a single-candidate super PAC is not the answer. The reality is that Bernie Sanders is the front-runner for the Democratic nomination because he is running a grassroots campaign. There isn’t a super PAC in this life or the next that could spend as much as Michael Bloomberg is spending.”

Both Warren’s and Klobuchar’s super PACs were seeded, in part, with money from EMILY’s List, which works to elect Democratic women who support abortion rights. The group donated $250,000 to both Persist PAC, which backs Warren, and to Kitchen Table Issues PAC, which backs Klobuchar.

“We are proud of the campaigns both Amy Klobuchar and Elizabeth Warren are running,” said Christina Reynolds, an EMILY’s List spokeswoman. “We know they would each be great presidents. While we respect their views and agree on the need for campaign finance reform, we believe this election is too important, and we want to do what we can within the bounds of existing law to support them.”

Warren’s reversal was especially jarring. Her campaign had previously directly called on outside groups supporting her to shut down. Tiffany Mueller, the president of End Citizens United, called on Warren to reconsider and said accepting the PAC’s help “undermines [Warren’s] campaign.”

This is incredibly disappointing. I agreed with @ewarren when she said, "The Democratic primary should belong to grassroots supporters and grassroots donors, not the rich and powerful."

This decision undermines her campaign. I hope she reconsiders. https://t.co/0k5RKMW1z8

— Tiffany Muller (@Tiffany_Muller) February 20, 2020

Warren’s rivals pounced on her reversal. “You can’t change a corrupt system by taking its money,” Sanders tweeted. Operatives for Buttigieg, whom Warren had slammed for his in-person high-dollar fundraising, suggested the former Harvard law professor was a hypocrite. (Warren, like Sanders, is still declining to hold high-dollar fundraisers for her campaign.)

Love HuffPost? Become a founding member of HuffPost Plus today.

“This is the problem with issuing purity tests you yourself cannot pass. https://t.co/045j85GDqx

— Lis Smith (@Lis_Smith) February 20, 2020

But the formation of Persist PAC is already creating benefits for her candidacy as she seeks to capitalize on a strong performance in Wednesday night’s debate: The group has booked more than $1 million worth of television ad time in Nevada and South Carolina, the next two states to vote.

As Warren tried to explain her sudden reversal on super PACs to an incredulous press corps on Thursday, she retreated to lines Democrats often deploy when Republicans question how they can support ending super PACs and dark money groups while simultaneously accepting aid from those groups to win elections. She wanted to change the system, Warren insisted, but wouldn’t unilaterally disarm in the middle of a competitive and crucial election.

She sounded, in many ways, just like every other Democrat.

Related...

Mike Bloomberg Spent $220 Million In January. That Is An Unimaginable Sum.

Elizabeth Warren Backtracks On Super PAC Support

The 2020 Democratic Debate In Nevada Was The Most Watched In History

This article originally appeared on HuffPost.