Taken by opioids: Winnipeg woman dies months after her mother

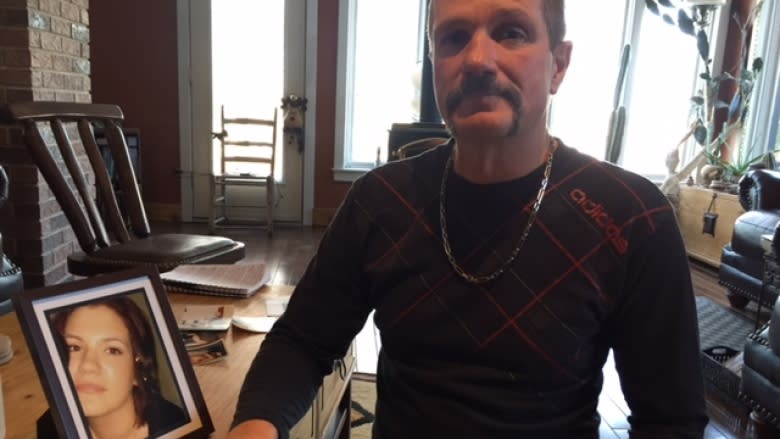

He did everything he could to ease his daughter's pain, but a Manitoba father was no match for the drug addiction that claimed the life of 31-year-old Ashten Cook, just months after her mother died from a fentanyl overdose.

Robert Warkentin, Cook's father, said friends' and family's worst fear came true after Cook disappeared for about three months.

She was found dead in a room at a hotel on Pembina Highway March 1.

"I knew this day was coming actually two months ago. And I've been looking for her and I've been phoning and emailing and driving around Winnipeg at different addresses a week ago before they found her," said Warkentin.

"I feel helpless, I feel like my hands are tied, especially the last couple months. Fatherly instincts were telling me I'm gonna have to find her or it's not gonna turn out good. I just couldn't. I tried," he said.

She was among an increasing number of Manitobans — at least 26 last year alone — who were killed by the dangerously addictive opioids, caught up in a perfect storm of multiple prescriptions, a lack of training for doctors, street drugs full of unknowns and lack of access to treatment.

Cook fought back against some difficult circumstances, but there was a lot of darkness in her early life.

She was born in Winnipeg and raised by her mother, Daneen Cook, of Grand Rapids, Man. Her father didn't have much contact with her from the ages of three to 16. Her mother was a teacher, and they moved a lot across the country.

"Her mom had addictions and she would do whatever that took to supply it. And my daughter got hurt in and about that," said Warkentin. Cook was physically abused and sexually assaulted at the age of 12 by one of her mother's partners, he said.

At the age of 16, Cook sought a court order that would sever legal ties with her mother. She got a place of her own and Robert gradually re-entered his daughter's life. Her relationship with her mother remained close, but volatile.

"So it was very hard for me as a father. It's a strange relationship. Even though your mother or your father might hurt you, you still desire to love your mother or your father. It was really hard for me to try to understand that she would still desire to try to move into another apartment with her mom, years later," he said.

Family friend Jen Storm said, of the bond between Ashten and Daneen: "They're both loving people that would do anything to protect their loved ones."

- OPINION: 'Long past time' to act on Canada's deadly opioid epidemic

Cook graduated from Gordon Bell High School and became a security guard at the Manitoba Youth Centre.

"I was so proud and happy for her. She had slugged it out, went against the odds, graduated, then she went and took this course, she did very well so you're excited for her. We helped her out with a new car and stuff," said Warkentin.

Prescribed opioids for pain

Then after a car crash in 2009 or 2010, a physician put her on opioids.

"The OxyContin thing with that car crash was for sure was a turning point for her life. They gave her way too much freedom with quantities of that stuff," he said.

She became addicted. Around that time, he said, she also lost her job.

As her life began to spiral, she would repeatedly get prescribed opioids for other injuries in addition to buying them.

Warkentin visited her at several different apartments across the city.

"One day I found a bottle, 120 OxyContin in one pill bottle from a doctor with her name on it. And I was so frustrated. Why are you giving a loaded gun to someone that can't make a proper decision? It's like giving a three-year-old a loaded gun," he said.

Cook stopped making her car payments, and about three years ago, was badly beaten up by a gang member.

"I rescued her from a women's shelter in Winnipeg," said Warkentin.

"She phoned me. When I got there there was my daughter with black eyes, teeth knocked out, broken ribs," he said.

That was the breaking point, and he knew he had to act to save her life. He brought her to a women's shelter, and his church, in Steinbach.

"She was battling for it, you know, and she was winning. She was doing pretty good. A lot of people poured into her. Gathered around and poured their time and love on her."

She stayed in a home with other women and completed the eight-month School of Ministers program at their church.

"She gave it her all, she didn't quit," he said.

Determined to go back to school, Cook began working towards a law degree at the University of Manitoba.

Undone by pain of mother's death

But on May 24, 2016, her progress came undone.

Daneen Cook was found dead in a home in Winnipeg after overdosing on fentanyl.

"Things went bad from there. And then things went really bad when she got $180,000 life insurance policy about three months ago," said Warkentin.

She withdrew; she wouldn't answer the apartment buzzer, she wouldn't answer the phone, only letting her brother inside when he threatened to call the police to check if she was alive.

"She'd answered the door and she was upset and she was distant and my son said all her mom's things were still in boxes and she was just in her room in the dark, she was just in a bad place. She was in a bad place."

The huge sum of money she inherited from her mother's death could turn her life around or end it. In December, she was staying with family in The Pas who were encouraging her to put it in a trust fund and seek help for her addictions.

On what would be their last conversation, she phoned her dad from The Pas on Dec. 26. Cook "never sounded so good," Warkentin said, as they talked about renovating a cottage to use it year-round.

Instead, she went back to the city.

On March 1, Warkentin got a call from police, telling him they were on their way to talk about some of his missing property. But he didn't seem to be missing anything.

"All of a sudden I knew. Instantly. This isn't about material things. The Holy Spirit kind of just prompted my heart and said, 'It's about Ashten.'"

Police told Warkentin the name of a woman who had been with his daughter when she died. The same woman had also been with Daneen the day she died. Warkentin believes she's a drug dealer.

At Cook's funeral in Grand Rapids Friday, Warkentin prayed for the woman as they both stood over his daughter's coffin.

"I spoke with her … and I told her that I was praying that she would change her heart and turn from the drugs before she was in the coffin next."

Dealing with the pain

Warkentin said while his daughter's death "feels like I got beat up with a sledgehammer inside and out," he's determined to be a good example for dealing with the pain, and to use his experience to help others make different choices than his daughter and her mother.

"All these young people are running from their pain and they're killing themselves," he said. "You got some hurt, you got some pain? Running from your pain doesn't always work. It ends up like this."

He's pleading with doctors to stop writing painkiller prescriptions to people who are hurting mentally. "It's too easy. It's easier than going to a gangster and getting drugs. And that's pathetic."

He said his daughter thrived when she was surrounded by family, and was "joyful." Growing up, she had always been the "anchor" among her friends, not letting anyone party too hard or get too out of hand with drugs and alcohol.

"Start recommending family members to gather together and [care] for one another rather than just pouring pills on them because that's just like here's a bottle of whiskey, here's a gun, see you later."

Paramedics that responded to the 911 call "worked like hell" to revive the woman who had overdosed on opioids March 1, according to Ryan Woiden, president of MGEU Local 911. In his haste to identify her, one man breathed in some white powder that flew up from the woman's metal purse. He was concerned, but finished the call, Woiden said. The paramedic was later admitted to hospital for possible opioid exposure, but did not have any signs or symptoms.

Police told Warkentin his daughter had been staying at the hotel for four days before the afternoon she died.

"You see somebody hurting in your family? Gather around them. Don't let them be alone. We attempted that, but I think it was too late. We didn't realize how broken she was," he said.

"We were trying. We were banging on the door. We were phoning. But I think it was a little too late."