How a team of Canadian grad students is setting the stage for the next lunar mission

In a classroom at Western University, a team of people is busy sending instructions to a lunar rover.

They're trying to guide the rover to an interesting rock and then use scientific instruments to analyze its features, in the hopes of learning more about the moon's geology.

Except the rover isn't on the moon, it's in a nearby field. And it isn't actually a rover, it's a tripod.

It may not seem like much, but this exercise will help lay the foundation for the next trip to the moon and train future generations of scientists to lead missions beyond our planet.

The team, which consists of graduate students and faculty at the London, Ont., university, is taking part in a simulation called CanMoon, funded by the Canadian Space Agency.

They'll be testing out procedures to operate a Canadian-made rover on the moon's surface.

For now, the group has just completed a dry run of their mission.

In August a field team will head to the Canary Islands, where they'll run the full simulation over the span of two weeks. The classroom at Western University will serve as "mission control."

Science driven

Christy Caudill, a PhD candidate at the university, says two smaller teams will guide the rover from mission control: science and planning.

"The science team is really responsible for moving the mission forward as these are science driven missions, wherein every rock we look at, every outcrop that we look at, we want to analyze that and figure out something about it," Caudill said.

"Planning are responsible for getting the rover from point A to point B."

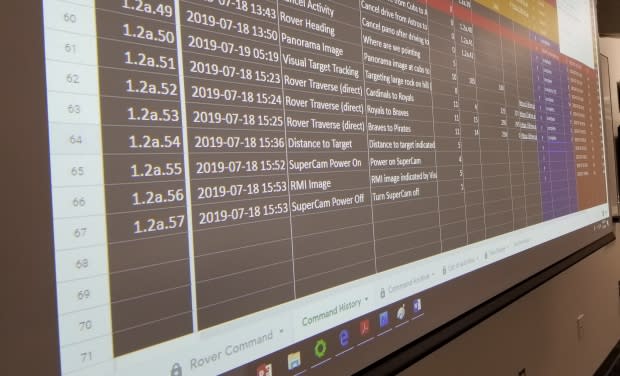

The planning team has to maneuver the rover using a series of operations, which are listed in what Caudill describes as a "souped up spreadsheet."

The spreadsheet is then used by the field team to move the stand-in for the rover. Once the rover is in place, Caudill says the field team begins taking images of the terrain and using scientific instruments to take measurements of the rocks.

All of that data will then be sent back to the science team for analysis.

The ultimate goal of the mission is to learn more about the lunar crust and how it evolved over time — although in reality, they'll be studying the black basaltic rock of the Canary Islands.

"We will get an idea of the composition and maybe the origin of rocks at our field site," said Zach Morse, who is in charge of the science team. "There are lava flows which come from deep inside the earth, so we might get a better idea of the composition of the earth's mantle and crust."

The volcanic terrain of the Canary Islands turns out to be a good stand in for the moon, which Morse says is full of volcanic rocks.

"The moon is a big ball that sort of cooled out of magmas a long time ago, so we're simulating sampling lunar materials of similar composition and in theory we would be able to get information about the deep lunar interior, which we can't do from satellites," he explained.

The next generation

The CanMoon simulation isn't just an exercise in gathering and analyzing information, though.

Similar simulations based on NASA's 2020 rover mission to Mars have helped form the operational procedures that will actually be used during that mission, Caudill said.

It also serves as an important training opportunity.

"This is important for Canada to position itself for training the next generation of people in planetary science and in engineering exploration to be able to man these missions as we go forward," Caudill said.

For Morse, the most exciting part of the simulation is getting a glimpse of what it will be like working in the field.

"We're as close to operating a moon mission as you could probably get without sending a rover to the lunar surface," he said.

"It's kind of what we've all been working towards here, as graduate students at Western, is maybe working eventually with a space administration. It's sort of like getting our foot in the door and getting a taste of what it will really be like someday."