This tech giant up for sale is a homegrown miracle – it must be saved for Britain

So, Brexit Tories, let’s see the colour of your money. So far, Brexit has meant billions spent on new, trade-inhibiting customs facilities, a proposed US trade deal that will necessarily compromise food standards to make us ill and a slump in inward investment. Not to mention deepening the crisis caused by Covid with the de facto no-deal Brexit. But now comes a chance to redeem yourselves, at least in part.

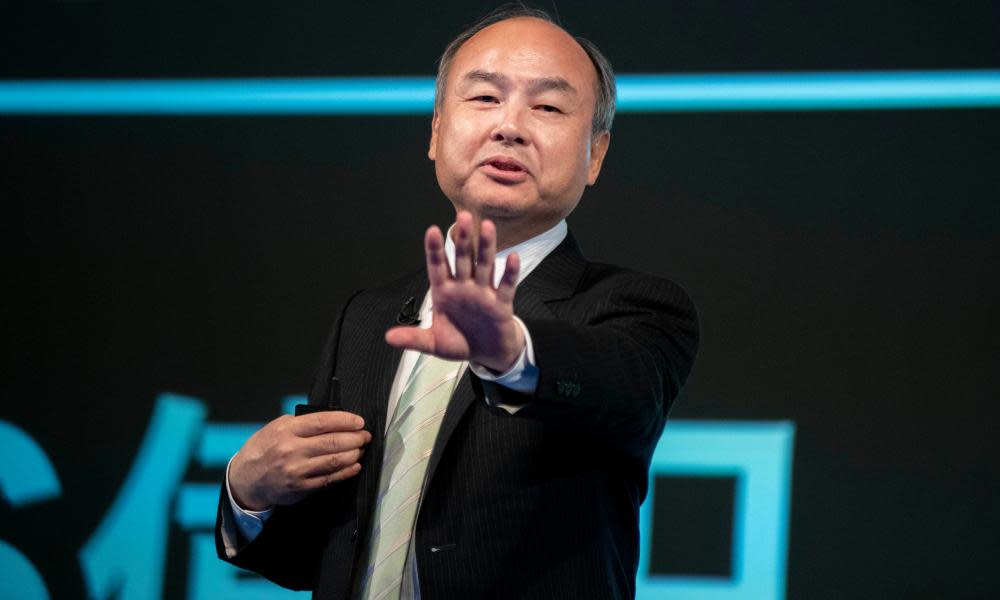

Weeks after the referendum vote, Britain lost its biggest and best technology company – Arm – to the predatory charms of the megalomaniac Japanese billionaire Masayoshi Son’s SoftBank. Son, who this year compared himself to Jesus, paid $32bn (£24bn), the highest price ever for a European hi-tech company.

The newly anointed prime minister and chancellor, Theresa May and Philip Hammond, joined with Nigel Farage to prove their pro-Brexit credentials by hymning, nonsensically, the deal as showing Britain was “open for business” (code for being asset-stripped). And, as Son correctly judged, venal City shareholders, ignorant of what they owned, were only too ready to pocket handsome profits.

Game, set and match to Son, except that four years later, as expected by anybody with nous, and despite the tech boom, he is now trying to sell Arm, which has languished under his ownership. It is available for no more than what he paid for it and presents a heaven-sent opportunity to reverse what never should have happened.

For what had attracted him to Arm still stands. Arm, founded in Cambridge, had become a brilliant company, creating the cleverest “architecture” in the semiconductor business. Essentially, it has invented and continues to invent highly efficient logical computational models, used in silicon chips. It licenses this intellectual property to myriad users – from Apple to Huawei – which customise the IP to their needs.

A future owner could almost trash Arm in the pursuit of its own commercial ends

It’s an approach that mixes open innovation – in the sense that once Arm has licensed the IP the users can do what they like with it – with a retention of proprietorial rights and ever-growing royalties. By 2016, it had become as important in its world as a Google or Apple – and British.

The genius is that it is a kind of public-interest commercial company: licensing state-of-the art instruction sets that can be implemented in silicon architecture by everyone. It was in nobody’s pocket. Its business, as its chief founder, Tudor Brown, acknowledges, relied on it never betraying its neutrality. The menace of Son was that, while, in fairness, he has kept his five-year promise (expiring next July) to retain Cambridge as Arm’s headquarters and built up its workforce, he could never offer the guarantee of vital independence. On top of that, he is a deal-maker who flips companies and strips off frontier IP. A future owner could almost trash Arm in the pursuit of its own commercial ends.

Nvidia, reported to be in advanced talks with Son, is just such a possible owner. Rooted in the games industry, it has found to its surprise that its processing units are much in demand as artificial intelligence applications mushroom. Son wanted to sell Arm to an industry coalition that might protect the company’s independence and business model. None could be found, so, desperate for cash, given a string of failed and written-down investments (WeWork, Uber etc), he is now having to sup with a buyer that can only destroy Arm.

Nvidia’s ambitions are scarcely hidden. Once it owns Arm it will withdraw its licensing agreements from its competitors, notably Intel and Huawei, and after July next year take the rump of Arm to Silicon Valley, just as Google has done with the British AI company DeepMind. Arm, and Britain’s hopes to be a player in hi-tech, will be dead.

Ownership is fundamental and the lesson of the story is that unless Britain creates the legal, cultural and institutional framework allowing companies such as Arm (or DeepMind) to have anchor shareholders – or simply allowing founder shareholders to have powerful differential voting rights as in the US and Canada – we are condemned to inferiority. But even now Britain could act. The government could offer a foundational investment of, say, £3bn-£5bn and invite other investors – some industrial, some sovereign wealth funds, some commercial asset managers – to join it in a coalition to buy Arm and run it as an independent quoted company, serving the worldwide tech industry. No doubt the permanent secretary at the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy will have heart failure (BEIS had reservations about the £400m spent on acquiring the satellite operator OneWeb), but if Britain is to develop an industrial strategy, this is how it must act.

The problem is that the Tories are so starstruck by the notion that anything private is always best – hence the succession of scandals, from Chris Grayling’s deal with a ferry company with no ferries to buying £150m of inoperable masks from a dodgy “entrepreneur” – that they don’t understand the need for public action on this scale and ambition. Equally, there is a powerful strain in the Labour party whose instinctive solution is to nationalise.

But Arm can no more prosper as a nationalised company than it can as a division of Nvidia. A successful capitalism is always about framing innovative private dynamism within a fit-for-purpose regulatory and ownership architecture designed by the state, a reality that neither major party has ever understood.

The open question is whether Brexit Tories, forced by reality, might change. This kind of audacious deal could appeal to Johnson and Cummings, a statement of intent to match China in our commitment to a decisive presence in 21st-century hi-tech. Brexit was meant to give Britain the freedom to make this kind of move. So Brexiters, show us the money. I am not holding my breath.

• Will Hutton is an Observer columnist