Testing sewage for COVID-19 could be 'early warning' system, Ontario researchers hope

A nasal swab isn't the only way to detect the virus that causes COVID-19 — scientists around the world have been able to track the presence of the novel coronavirus in sewage.

Now, a team of researchers at Ontario Tech University in Oshawa, Ont., is monitoring wastewater in Durham Region with the aim of giving public health units around the province a COVID-19 early warning system.

"We think it's important and obviously timely," said Denina Simmons, an assistant professor at Ontario Tech.

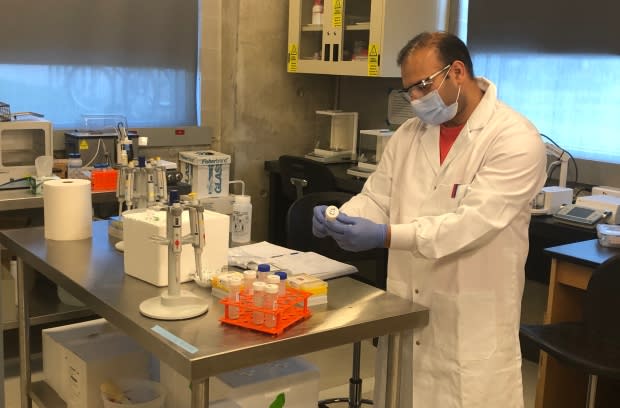

On a tour of her lab, Simmons demonstrated scientific equipment that can detect the proteins specific to SARS-CoV2, the coronavirus that causes the COVID-19 illness.

"When human beings are sick, they shed the viral particle through their breath, and through their urine and feces," she said. "When that goes down the drain, down the toilet and into the wastewater catchments, we can detect the virus."

One key feature of monitoring wastewater is that it can detect the virus before people show the symptoms that would prompt them to get tested.

Such a finding from a particular sewage treatment plant could show the local public health unit which part of its community is seeing evidence of infections. In turn, that could help officials decide where to direct testing resources in an effort to track down individual COVID-19 cases.

The team at Ontario Tech is collaborating on the project with colleagues around the province, including at Ryerson University in Toronto and the universities of Ottawa, Waterloo, Guelph and Windsor.

"We are all working on very small dribs and drabs of funding," said Simmons. "We would love to see there be an organized provincial plan."

She said the researchers would like to develop their methods and pass them on to the public health units and municipalities to conduct the testing more frequently.

Currently, engineers at four of Durham Region's 11 wastewater plants take samples every few hours and currently send a week's worth of samples to the researchers' labs at once.

"We just thought it was a fantastic opportunity to partner with the university on something that will eventually help our our health department in terms of COVID tracking and tracing," said Sandra Austin, director of strategic initiatives for Durham Region.

"It's almost like an early detection system," said Austin in an interview. "It gives us a much better indication of where we might have outbreaks in the future, because there's actually the ability to test for the virus within wastewater up to five days before symptoms would start to appear."

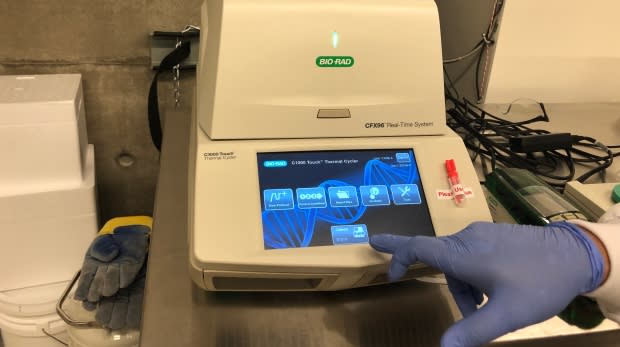

The equipment used by Ontario Tech for detecting the virus in Durham's wastewater samples includes a thermal cycler, also known as a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) machine. It analyzes the samples for the genetic material of the coronavirus and can find out not only whether there is COVID-19 in the sample, but how much.

"This is probably the most sensitive experiment to do, where we can actually detect really low levels," said post-doctoral fellow Golam Islam as he ran the device in a basement lab at the university's science building.

It's a similar process to testing individual samples from nasal swabs taken at one of Ontario's COVID-19 assessment centres. The province is currently testing around 25,000 such samples per day.

The researchers contend that sampling conducted from wastewater collection sites around the province could screen many times that number of people daily. They say the cost of testing one sewage sample from an entire neighbourhood is comparable to the cost of testing one person with a nasal swab.

The wastewater method could also be used at the level of a large building or institution, such as a university campus or school, to monitor for early signs of an outbreak.

The applicability of this was borne out last month at the University of Arizona, which detected the presence of COVID-19 during daily monitoring of wastewater from a student dormitory. A follow-up testing blitz in the dorm found two cases, and university officials say that quick response prevented the infections from spreading.