Throwing Muses’ Kristin Hersh on the Music That Made Her

Kristin Hersh has spent a lifetime battling music-industry sharks—sexist label execs, capitalist cutthroats, gun-toting club owners—first in her band Throwing Muses, which she founded in 1980, and then as a solo musician. She eventually learned to handle them and has the scars, and stories, to prove it. But right now, it’s the sharks with fins and teeth that concern her.

Hersh, 54, is out in Encinitas, California to watch her youngest of four sons, a professional surfer, compete. “I didn’t know a kid could even have that job,” she marvels. “He’s 17, but he’s still my baby. I bake him cookies to cheer him up and shit. So the idea that he’s in these ice-cold, deadly waves, swimming with sharks...” She trails off into laughter. “He says that sharks are healthier than rock clubs, which is true—but not if they’re biting your legs off.”

Hersh was just 14 when she co-founded Throwing Muses with her half-sister, Tanya Donelly. By the time she was 20, the Muses were signed to the iconic British label 4AD—the first American band to land there, paving the way for fellow Boston alternative rockers the Pixies. By 22, she had signed to Warner Bros. subsidiary Sire, kicking off nearly a decade of strife with her major-label keepers. She says that her surfer son now confronts similar quandaries to the ones she faced, “seeing how corporatized your passion can become, and how hard you have to fight.” The antidote to selling out, she suggests, might be opting out—“Stick your middle finger up and live your passion”—even if that means working a day job to support yourself, in order to keep your art pure.

But Hersh is one of the lucky ones. She eventually got out of that major-label contract and took the band independent. With her hard-touring trio 50FootWave, she pioneered name-your-own-price releases and Creative Commons licenses. She raised her boys on the tour bus, reflecting her own unconventional upbringing: She spent her early years on a hippie commune in Georgia, and attended Woodstock as a 3-year-old. (“If I do have a memory of it, I made it up,” she says. “But there were a lot of festivals and face painting and high people and beads and shit then.”)

All these years later, her passion and her day job remain one and the same. In 2018, she released Possible Dust Clouds, her 10th solo album. Last month, Throwing Muses returned from a seven-year hiatus with Sun Racket. The record is lean, immersive, and groove-heavy, tapping the vein of hardscrabble psychedelia that defines their best work.

Here, Hersh looks back on the music that has soundtracked her defiantly unconventional path.

“Whole Heap of Little Horses” (Appalachian folk song)

Kristin Hersh: My parents are from Lookout Mountain in Chattanooga, Tennessee—a Southern Baptist upbringing. I’m from Georgia, originally, and my early childhood was infused with Appalachian folk songs—music that was written by no one, which is key to understanding what music really is. I love the faceless definition of true folk, which is a song that’s probably Celtic in origin, carried across the sea, and altered by all the voices who sang it. The same with blues songs, which changed as they walked from town to town. Some songs retain their bones and some become the emperor’s new clothes. I think the fact that the Carter Family drove around trying to monetize it is where it all went dark. I’m still not sure musicians should be paid other than passing the hat, because we don’t own moments of inspiration. There’s no genius, there are only moments. And that monetizing, corporatizing thing becomes very vivid when you contrast it with music that was created outside of that system, which is what I’m trying to do now. So it was a good place for me to start.

Philip Glass: Music in Twelve Parts

When I was 10, I probably still let my dad—his name was Dude—choose records. Having Philip Glass as a soundtrack to your home life is really tense, I have to say. But not un-beautiful. I was taking classical guitar, and my dad would blast the Clash, and I would play leads along with them, like karaoke. I’m grateful to them for that. And Talking Heads were an education of sorts. A little more art school than I really wanted my life to turn out, but Throwing Muses stepped right into their shoes a few years later. We started playing Providence, which was the scene they were from. I’m sure they helped open the door to what we were doing. It was a sea of glasses, 800 art-school kids.

X: Los Angeles

At 15, I had my own band, Throwing Muses, and loved anybody who sounded like us, like X and the Violent Femmes. That’s an obnoxious thing to say, isn’t it? I didn’t have time to be influenced. We were too young. We come from an island, [Newport, Rhode Island], where you’re either a skater or a surfer or you’re in a band. And we didn’t skate or surf. I was just this little dork girl.

This dude owned a store, Doo Wop Records, and he would let me return a record if it sucked. I tried not to return them, but I didn’t have a ton of money. And he said, “Well, I want you to keep listening.” So I did, because of him. He wasn’t even a nice guy, but he thought music was important, and he knew that I thought it was important. That dude was amazing. Cold, angry, wonderful. I saw him a few years ago on tour and we both cried and hugged each other.

Volcano Suns: “White Elephant”

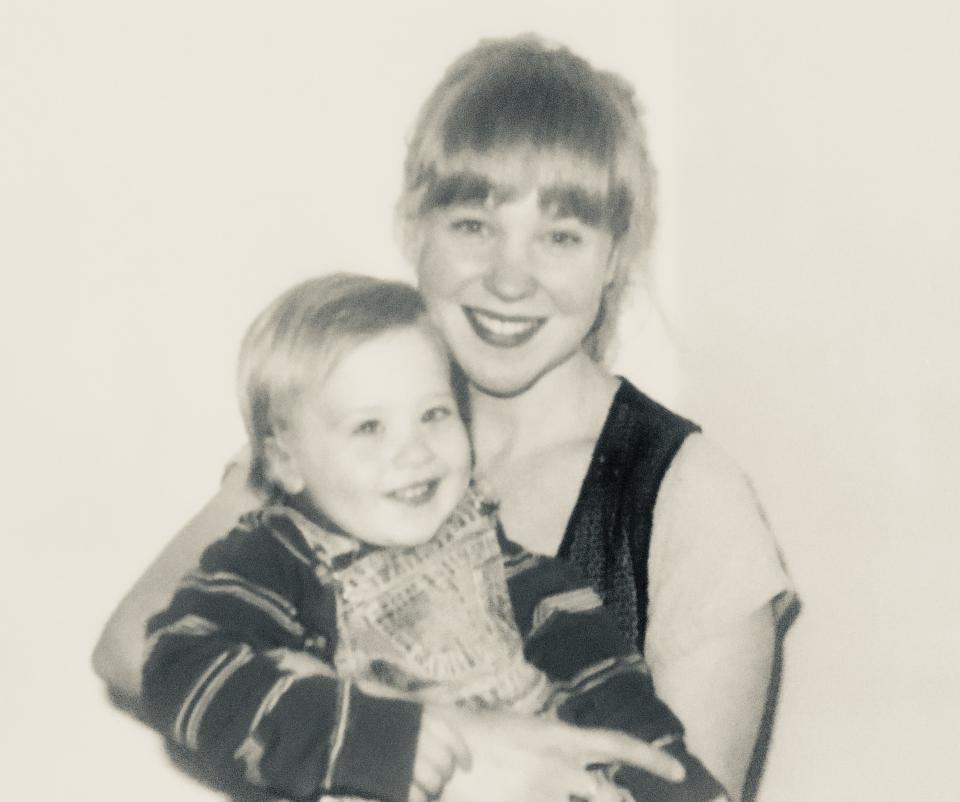

At 20, I was listening to my Boston friends: Pixies, Volcano Suns, Thalia Zedek. But I had a toddler, so I also played Appalachian folk songs again. Full circle! We went to Boston because the Providence scene was mired in garage rock—as was the Boston scene, but we didn’t know that yet. I couldn’t stand the energy in Boston—the ugliness, the pollution, the noise. I just love nature so much. Hippie chick! I just wanted to go back to the ocean, so I did. I lived a clean life back on the island, where songs are easier to hear. But the Boston scene was very supportive. The bands would become audience members, and then some other audience members would step on stage and play.

Throwing Muses

Ry Cooder: Paris, Texas Soundtrack

My music was very infused with darkness. I felt like it was celebratory, but it’s still intense, and it can be tough for me. When I was 25, I tried to break up my band because I felt obligated to no longer participate in an industry that denigrated women. I only listened to instrumentals. Mostly Ry Cooder’s Paris, Texas Soundtrack and classical stuff. I have a problem with the voices and lying in music: You turn on the radio and all you hear is lie, lie, lie, lie, lie. You can hear lies in instrumentals, too, but when you find the good ones, it’s very freeing and heavenly. I think the lies are just hell, so I’d rather go to heaven.

Throwing Muses: University

I knew not to sign with a major, yet when Ivo [Watts-Russell, the co-founder of 4AD] told me to, I trusted him. I thought, Well, better us than liars. But eventually you realize you’re sitting across the table from the devil. I decided, “Well, then, I’m outta here. I’m going to break up my band.” They said, “OK, but we own you. We don’t have to release anything you do. You’re half a million dollars in debt. Now you’re in music jail: We know that you want out, so you’re fucked. We’re going to bury you.” And they did.

Then my drummer was like, “Let’s be a band that doesn’t give a shit, because we are a band that doesn’t give a shit.” It was actually really fun from that point on. We did a few fuck-it records that we had a beautiful time making: Red Heaven, University, Limbo. Those are our biggest records, and they happened when we said, “Fuck you, we’re not going to bullshit anymore. We’re not going to give you any songs that suck, and I’m not going to do fucking fashion shoots.” We kind of won, and we never really stopped winning.

Throwing Muses

Vic Chesnutt: “Bakersfield”

I traded my first solo record for my contractual freedom from Warner Bros., and while I toured that record, I met Vic Chesnutt. When you meet Vic, it’s hard to listen to much else. “Songwriter” is something you’re born as, and it’s not great—it’s like being pregnant for your whole life. Most of us die young. Vic Chesnutt was born a songwriter. He had moments of grace that he could not help. He was sort of lacking the armor that most of us have. We’re familiar with that. It’s even a cliché, like Nick Drake or Elliott Smith. He was one of those. [Chesnutt died in 2009, at age 45.]

He didn’t always write great songs, and that to me was proof of his genius—that he sucked so bad when he wasn’t inspired. And he would laugh, saying, “I just love writing songs so much that I have to try.” And I’m like, “Dude, you can’t try.” He’s like, “I know! I’m going to do it anyway!” Sadly, those are his most celebrated moments. You know, you lie, and they love it. But the depth can be found in the quieter, more secret songs. He was capable of unimaginable depth. Songs like “Rabbit Box” and “Bakersfield.” He just didn’t last very long. It’s not an easy way to live. Eventually, I wrote a book about him.

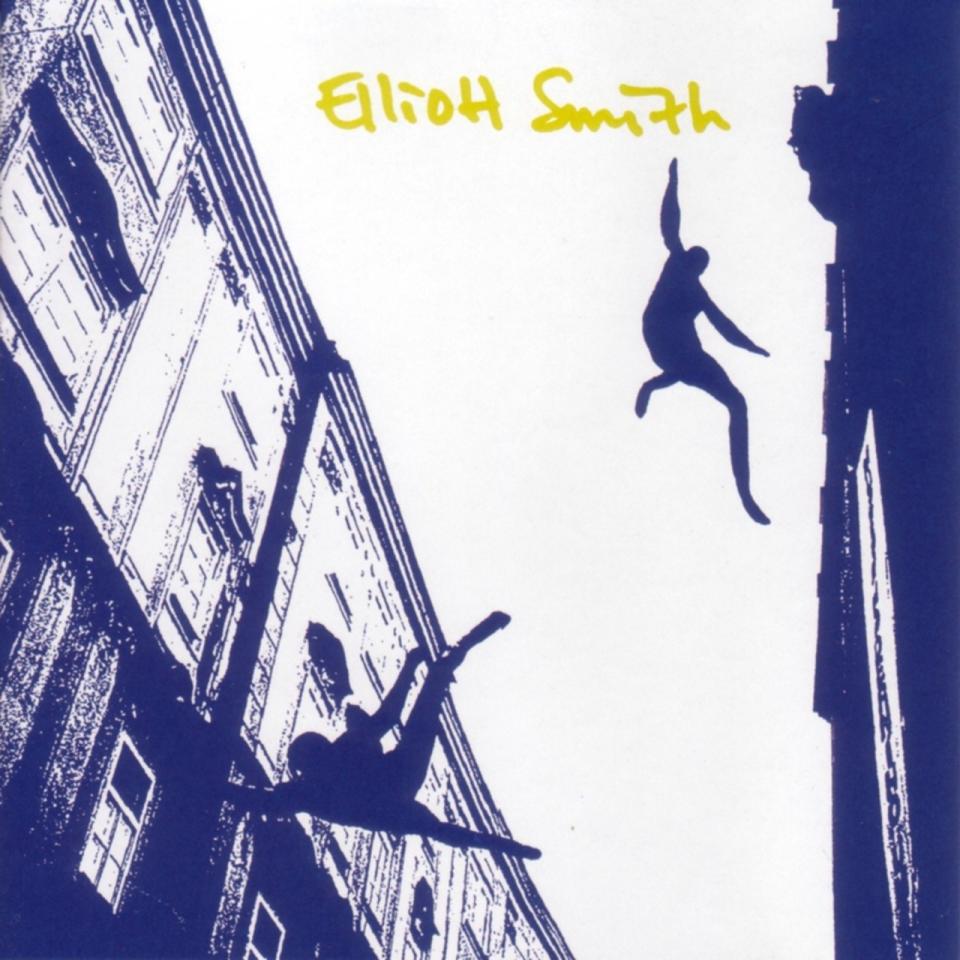

Elliott Smith: Elliott Smith

I’d started 50FootWave by then and was pretty much living on the road. I’d go on stage solo at about 8 p.m., Throwing Muses went on about 10, and 50FootWave played at midnight. The louder you are, the later you are. We’d be loading out at 3 a.m. I had a bunch of kids by then, and I would know that the babies would be up a couple of hours later. There were moments where I thought, I’m going to probably die. But I also thought, I have it all, all of it—I get the whole world. It was so fun.

Yet you’re used up completely by a band like that. Physically, emotionally, we’re like athletes, and we live like athletes. We are very healthy people and we would die if we weren’t. We were touring like 300 days a year, and I was raising kids on a bus. There is a certain amount of peace in that maelstrom, during the playing. The noise I find to be very peaceful, like the ocean or the eye of a hurricane, but the screaming that I do is shaking my insides. It feels like perforated lung tissue. Then the babies are up, so I’m not sleeping, and sometimes there’s no food or showers. It’s a hard life, and we needed peace, so we listened to real quiet music.

Throwing Muses Perform In Glasgow

The Legend of Zelda Orchestral Soundtrack

I curated my children’s entire soundtrack, because they only lived in my world. My kids couldn’t go to school. They made friends all over the world, but they only saw them for a day. They were raised in a kind of tribe, if not cult, because music really was a spiritual endeavor to us.

They are now out in the world and they have all come back to me with, “Mom, the world is not the bus!” And I say, “Well, yeah, sorry, but that’s why the bus was the bus.” And their response is, “Well, what do we do?” Because the bus was passion and laughter and love and kindness and tears—a lot of deep peace and a lot of adventure. And then the world turns out to be this kind of flattening plane, that is mostly engaged by fear and anger and boredom. And they don’t know any of that. There’s an alive quality to aliveness. That’s all. And kids are alive. So one soundtrack that helped us bridge those different islands was an orchestra that plays the Legend of Zelda Soundtrack, and they do it really well.

Quest for Fire: “The Greatest Hits by God”

I crave total engagement with music when I’m on a book tour. A set will take everything out of you and leave you at peace, because you gave all that you can, and there’s an uplifting nature to that. Whereas a book tour—I love writing and I think my books are very musical, but they’re not music. So the more book events I do, the lower I get, day after day. And I crave noise, because books are quiet.

I even had a one-woman show that I toured called Paradoxical Undressing, which has music in it. I played a lot of theaters and festivals and art museums, and it was successful. But that’s not where my head is at. I’m looking to see where the aliveness is. And I suppose it wasn’t alive, because it was killing me every night. It felt like it was taking more and more and more, instead of music, which gives more and more: It opens you and clears you out. So music becomes very, very important on a book tour, just to keep reminding me of what giving is and what humanity is and what respect is.

Originally Appeared on Pitchfork