How tiny babies are revealing big clues of early life

A newborn's first few days of life is fragile and potentially dangerous, navigating a world full of viruses, infections and bacteria. Many around the world don't survive.

While doctors and researchers have traditionally had few clues about what is happening to a newborn during this critical time, a new international study involving the University of British Columbia (UBC) may provide doctors with a roadmap for better survival strategies.

"A large proportion of childhood mortality is newborn mortality and there's a lot we don't know about neonatal immunology," said Dr. Jeffrey Pernica, head of pediatric infectious disease at McMaster Children's Hospital in Hamilton.

The study, published in the journal Nature Communications, looked at two groups of newborns in different parts of the world: Papua New Guinea and Gambia.

The researchers compared two tiny blood samples — less than a quarter of a teaspoon from each newborn — with the first being taken at birth and the next taken later in the first week of life.

What they found was dramatic: Thousands of changes over that first week of life, including specific genes and immune cells being activated and proteins being produced.

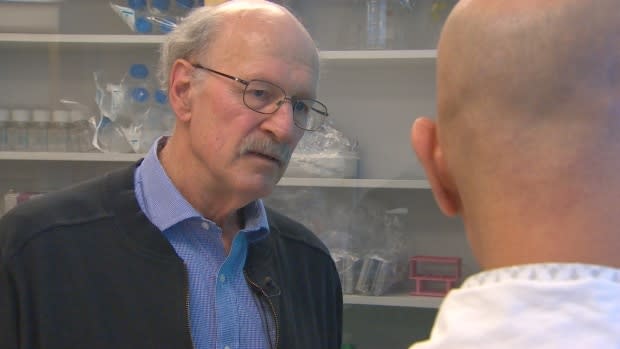

"I don't think we knew how the infant's immunity changed over time," said Canadian microbiologist and study co-author Bob Hancock. "I don't think we appreciated the staggering number of changes that are occurring."

Hancock's lab at UBC performed the blood work on the tiny recruits. Up until now, the biggest challenge for scientists gathering data had been sourcing a large enough blood sample from a newborn to provide comprehensive information.

Hancock's team pioneered a technique using sophisticated software to get a huge amount of data from a tiny drop of blood.

"We saw a turn on of dedicated cells called neutrophils; neutrophils are the body's way of fighting infections. We saw a turn on of proteins called interferons, which is the major anti-viral or viral-fighting mechanism in the body. And we saw a turn on of a protein called complement — one of the most important ways of fighting bacteria," said Hancock.

"So in these ways, the infant was adapting to try to resist the challenges of the first week of life, recovering from the stress of birth."

Common developmental path

What also surprised Hancock and the global research team were the common biological threads between two sets of newborns born thousands of kilometres apart. It suggests that the molecular changes aren't random, but instead follow a specific developmental pathway.

The researchers say that finding could provide doctors with better opportunities to save more infants, particularly when it comes to immunization.

"This common trajectory is exciting, as it allows us to ask bigger questions about the differences between different populations and the impact of biomedical interventions, such as vaccines, on development," said Dr. Ofer Levy, one of the study's senior authors and a physician with Boston Children's Hospital.

In most of Canada and the developed world, infants are given their first vaccine at two to three months, for diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus and polio. Some provinces also offer vaccines for influenza type B and hepatitis B. The schedule is a bit different in Canada's North, where newborns and infants in Nunavut also get a vaccination for tuberculosis because of a high prevalence of the disease.

This latest research could potentially change how all doctors think about the best time to vaccinate a baby.

"We'd really like to know more about whether we can actually start doing these vaccinations even earlier in the infants to give them a better chance of fighting off the devastating diseases that vaccines protect against," said Hancock.

For Pernica, the study offers other things to consider when looking at how to protect newborns in those early days, including whether more specific testing can be done at birth to determine which baby may get sick, as well as providing more information to new mothers.

"This study will add a lot to what scientists know in the future," he said.

The study's main limitation was its small sample size: Only 60 babies were involved. But the researchers say they plan to increase that number through subsequent research in the hopes of providing the world's most vulnerable with a fighting chance as early as possible.