The tremendous explosion and impact of the Tonga volcano, explained

The tremendous eruption of the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai volcano was the blast heard and seen around the world.

Shock waves rippled at least twice around the globe, moving at the speed of sound as they radiated outward from the remote eruption about 40 miles north of the largest island in the Kingdom of Tonga.

“I am absolutely amazed at the acoustic wave still making laps and ripples around the world,” said Brian McNoldy, a senior research associate in marine and atmospheric science at the University of Miami. He observed yet another pressure wave in Miami Tuesday night, three days after the initial blast.

“That was remarkable," he said. "An explosion that can create such a wave is incomprehensible to me.”

He’s not alone. One of the biggest eruptions in decades sparked high interest around the world, though it was tempered by the loss of life and destruction in Tonga. Scientific researchers have been impressed not only by the eruption's massive size, but by the volume and timing of data being collected and shared.

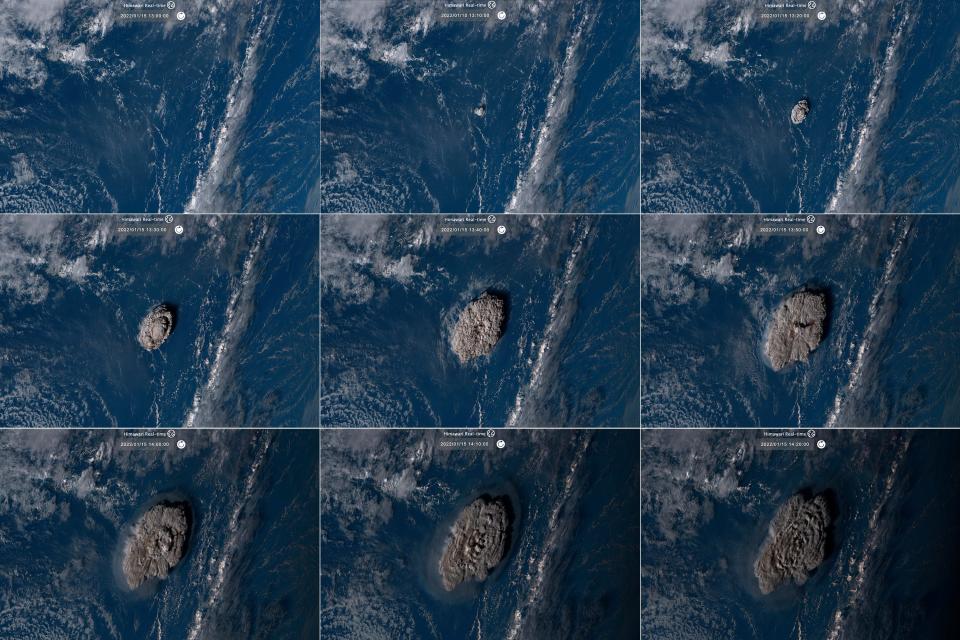

Sophisticated satellites and monitoring equipment captured the mushroom cloud of ash, seawater and steam and its resulting waves in the atmosphere and oceans in real time. Eyewitnesses and researchers posted observations on social media, comparing notes on the flow of data that will be studied for years to come.

In those terms, the event is unprecedented, said Dave Snider, tsunami warning coordinator for the National Tsunami Warning Center. “Our ability to measure and understand this is mind-boggling.”

Several other factors also made this eruption notable. For example, because it occurred in the daytime, at least three satellites caught the explosion in true color, yielding spectacular images.

More: See before and after images of Tongan islands after the volcano eruption

The blast shot up from under the ocean, churning up huge amounts of water into the sky and turning great volumes of water into steam. During an underwater eruption, magma reaching temperatures of more than 1,000 degrees rushed into cold seawater.

That reaction helped create the extreme force that propelled the cloud of water, steam and ash more than 100,000 feet into the atmosphere, said Dave Schneider, a research geophysicist at the U.S. Geological Survey's Alaska Volcano Observatory. It puts “a more powerful rocket at the bottom” of the pillar.

Video: NASA shares satellite video of the eruption

That's one reason why seven hours after the explosion, and more than 5,500 miles away, the eruption was heard as a low rumble between Anchorage and Fairbanks. Pressure fluctuations were measured in Alaska, the mainland U.S., Europe and Africa.

Those pressure waves would continue circling until they were no longer noticeable by instruments, Schneider said.

Waves also traveled along the ocean. While movies picture tsunamis as a single wall of water, they’re really a series of powerful waves carrying tremendous force as they rush over beaches and into tidal inlets. Wave heights can vary based on the slope of the surface leading up to the beach, and occur over a period of hours. Water — heavy and destructive — can wreak havoc even at 12 inches deep. Tsunamis combine volume, buoyancy and forward motion in extremely dangerous currents.

On Saturday, the first big waves washed over the western shores of the closest islands in Tonga within minutes and poured inland. At least three people died, and the islands were blanketed in ash, public officials there said Tuesday. At least 50 homes were destroyed and another 100 severely damaged.

From Tonga, tsunami waves traveled across the Pacific in all directions, from Australia to Japan and from Alaska southward to Chile. A maximum tsunami height of 5.7 feet was reported in Chanaral, Chile, more than 6,000 miles eastward, according to preliminary reports from the Pacific Tsunami Warning Center. To the west, a tsunami height of 4.6 feet was reported on the island of Vanuatu.

Along the U.S. coast, a maximum tsunami height of 4.3 feet was reported in Port San Luis, California, the warning center reported.

Tsunami wave heights of up to a foot or more were detected in Alaska, Kauai, Peru, and Japan, while heights between a few inches and a foot were reported elsewhere in Hawaii and in Australia, Costa Rica and Acapulco, Mexico. The Associated Press reported two people drowned in the waves off Peru.

Tsunami waves were even measured in the Caribbean, said Schneider, the result of the traveling sound waves.

Scientists are still in the earliest stages of understanding all that occurred, what caused the massive eruption and how it compares to previous events, Schneider said. “It’s right up there with the biggest eruptions we’ve seen in the last several decades."

Eruption size is generally measured by the volume of erupted material, not the size and height of the cloud shooting into the sky, he said. Researchers measure that material by calculating the amount of sulfur dioxide released. It shows up in the magma in satellite images, looking like bubbles in champagne.

It appeared from early estimates that sulfur dioxide emissions were not great enough to cause any of the climate cooling that occurred after the eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines in 2001, he said.

Saturday's eruption occurred between two islands, Hunga Ha'apai and Hunga Tonga, where a large volcano and caldera lay beneath the sea surface, said Marco Brenna, a senior lecturer in the geology department at the University of Otago in New Zealand, who has studied the volcano.

The two islands were joined after eruptions in late 2014 and early 2015 formed a new cone of material, Brenna said. Based on satellite images, he said Saturday’s eruption destroyed the remnants of that cone and left the islands standing separately once more.

More: Read more about the volcano's history here, from the Smithsonian

Brenna said the arc of volcanoes near Tonga seem to follow a sequence of growth and destruction that causes recently formed cones to collapse and form calderas in large, explosive eruptions.

In this case, researchers suspect there was “some kind of major mass movement,” mostly underwater, said Andreas Schafer, a geophysicist at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology in Germany. Such movement could expel the magma, exposing it to a rush of seawater. “Whether it was a collapse of the caldera or a large landslide along the flank of the underwater volcano is not clear. It would need on-site investigation to find out.”

NASA researchers had been studying data from the region for the past seven years, with help from the Canadian Space Agency and commercial satellites, as well as its own satellite and field data, said James Garvin, senior fellow and chief scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center.

This week they compared the total volume of the combined island before the blast from its seafloor base to the measured volumetric loss to nearby islands. Coupling that with satellite images of the plume, the researchers put a preliminary estimate on the total kinetic energy of the blast at the equivalent of 6 megatons of TNT, with a 1.5 megaton range of uncertainty, Garvin said. That does not include the thermal aspects of the eruption, which could also be multiple megatons of equivalent energy.

It remains unclear whether the eruption was a climax in the life of the volcano or a sign of things to come, for that volcano or others in the region.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Tonga volcano eruption: How science explains tsunami, extreme blast