Top 10 political travel books

All travel is political. You can’t set foot outside the house without encountering other people, which inevitably prompts consideration of their lives in comparison to yours.

The Road to Wigan Pier by George Orwell clarifies the process by dividing it into two distinct parts – observation and reflection. To begin with, he describes the poverty and hardship he witnessed during a two-month spell in Yorkshire and Lancashire in 1936. Then he considers his favoured solution – socialism – and the obstacles to its widespread adoption. Some of it has come to seem petulant and outdated, as with his swipe at “the dreary tribe of high-minded women and sandal-wearers and bearded fruit-juice drinkers”, but there are also insights that remain relevant: “Even the fascist bully at his symbolic worst … does not necessarily feel himself a bully; more probably he feels like Roland in the pass at Roncevaux, defending Christendom against the barbarian,’ he writes.

Yet today’s greatest political challenge – confronting the climate crisis – transcends the kind of nationalist squabble that Orwell understood so well. In my book, The Great Flood: Travels Through a Flooded Landscape, I travelled around the country, visiting places that had flooded, and meeting the people affected. I wanted to try and understand the emotional and psychological effects of being flooded, because flooding is the way that climatic upheaval is making itself felt in Britain.

I didn’t write about policy or engage in scientific debates about climate change: I explored people’s response to this experience and their attempts to hold authority to account. What could be more political than that? Here are 10 other political travelogues – defined in equally broad terms - that I love.

1. English Journey, or The Road to Milton Keynes by Beryl Bainbridge

JB Priestley’s English Journey, which he described as “a rambling but truthful account of what one man saw and heard and thought and felt during a journey through England in the autumn of 1933”, was the first Great Depression-era travelogue, preceding Orwell’s. Fifty years later, in the depths of another recession, Bainbridge set out in Priestley’s footsteps. The fact that she was accompanied by a film crew of six men and one woman does not detract from her distinctive voice, which is funny and self-deprecating. Her visit to her home town of Liverpool - more memoir than reportage - is particularly moving. (“The blackened city sails in an ocean of white cloud, perpetually racing before the wind.”)

2. The Illustrated Journeys of Celia Fiennes, 1685–c.1712 (ed Christopher Morris, 1995)

Think of a place in Britain you know and love, and there is a fair chance Celia Fiennes will have been there 300 years before you. For a woman to travel around the country, on horseback, in the late 17th and early 18th century, was revolutionary in itself. Writing it up made it even more so. Her account of these journeys – first published as Through England on a Side Saddle – is one of the founding works of British travel writing. There are stately homes, but there are also towns and cities, and acerbic verdicts on places she didn’t like. Ely, for instance, is “a harbour to breed and nest vermin”.

3. The People of Providence: A Housing Estate and Some of Its Inhabitants by Tony Parker

An inspiration when I was writing my first book, about the inhabitants of Western Avenue, the road that leads west out of London: I did not have the skill or the self-effacing discipline that Parker uses to present the stories of the inhabitants of an unidentified south London estate in their words alone, but I drew constant reassurance from the proof that there were undiscovered worlds close at hand.

4. Naples ’44 by Norman Lewis

Travel of a different kind – in the vanguard of an occupying army. Lewis, who was one of the great travel writers of the 20th century, arrived in southern Italy during the Allied invasion of September 1943, as an intelligence officer attached to the US Fifth Army. To begin with, his brilliantly observed diary entries deal with the chaos and brutality of the war, but at the beginning of October, he arrives in Naples, and despite the terrible privations of life in a war-ravaged city, finds himself enchanted by the city and its inhabitants.

5. The Jaguar Smile by Salman Rushdie

Rushdie visited Nicaragua during July 1986, when the Sandinista government was battling to survive in the face of hostility from the US and the US-sponsored Contra rebels. Since he was a patron of the Nicaragua Solidarity Campaign in London, he was not “a wholly neutral observer”. He was dismayed by the censorship in force, but “el escritor hindú”, as he was called, could not bring himself to condemn a government led by a poet, Daniel Ortega. Rushdie’s “postcards” from Nicaragua, as he calls this record of his trip, were once an insight into a venture that failed. But since Ortega won power again in 2011 and 2016, their historical significance has changed again.

6. Sleeping on a Wire: Conversations With Palestinians in Israel by David Grossman

True to its title, the brilliant Israeli writer relays long conversations with Palestinians in Israel, his not-quite-compatriots, interspersed with agonised reflections on the compromised nature of every encounter. These meetings add up to a kind of foreign travel in his own land. “Do I actually understand the nature of Jewish-Arab coexistence?” he writes: “‘And what does it demand of me, as a Jew in Israel? How much room am I really willing to make for ‘them’ in the Jewish state?”

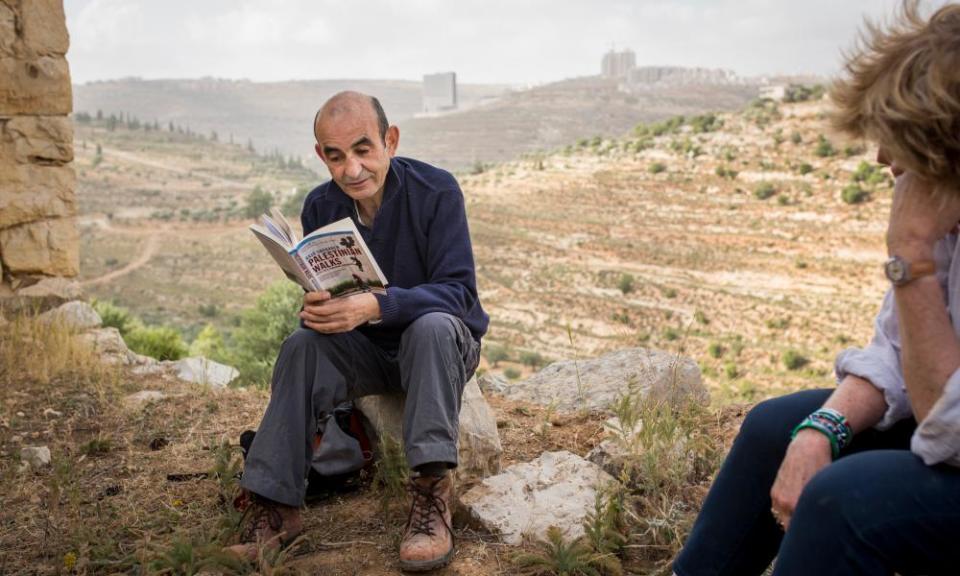

7. Palestinian Walks: Notes on a Vanishing Landscape by Raja Shehadeh

The essential counterpoint to Grossman – a reminder that Grossman, for one, would not need, that some people are denied the luxury of going anywhere at all. Raja Shehadeh, a lawyer and writer from Ramallah, describes the ever-tightening Israeli grip on the West Bank through an account of six walks conducted between 1978 and 2006. At the beginning of the book, he describes the Palestinians’ traditional habit of setting off on a kind of aimless ramble, called a sarha, that might last for days or weeks, but by the time of his sixth and final walk in 2006, he says they are moving through their own country “surreptitiously, like unwanted strangers, constantly harassed, never feeling safe”.

8. Wanderlust: A History of Walking by Rebecca Solnit

Walking is always a political act, Solnit says, for “the history of both urban and rural walking is a history of freedom”. It is also “an unwritten, secret” history that “trespasses through everybody else’s field – through anatomy, anthropology, architecture, gardening, geography, political and cultural history, literature, sexuality, religious studies”. Few other writers could navigate a path through such a maze. Solnit’s reading is so wide-ranging that she lays down a secondary trail across the bottom of the page, an unfurling tickertape of other writers’ thoughts.

9. Private Island: Why Britain Now Belongs to Someone Else by James Meek

Meek shows how the widespread privatisations of the last 30 years achieved exactly the opposite of what they set out to do: instead of passing control of essential public services such as water and power to small investors, and creating nimble, fast-moving operations for a competitive market, they handed them over to foreign, state-owned companies or oligarchic investors. The latter now milk their captive markets for profit. The consequences are dramatised through Meek’s encounters with the people affected and vivid descriptions of the places he visits.

Related: Top 10 eyewitness accounts of 20th-century history | Charles Emmerson

10. A Guide to the New Ruins of Great Britain by Owen Hatherley

Another book that emulates Priestley’s English Journey, though it takes in Wales and Scotland as well. Hatherley, who is an architecture critic, set out in 2010 to survey the school of buildings bankrolled by the PFI (Private Finance Initiative) that he calls “pseudo-modernism”. Yet his disdain for the “urban renaissance” of the Blair and Brown years is offset by his “constant surprise and fascination at just how strange, individual and architecturally diverse British cities actually are”.

• The Great Flood by Edward Platt is published by Picador. To order a copy, go to guardianbookshop.com. Free UK p&p on orders over £15.