Turtle Island Reads helps spread word about Indigenous literature

Sofia Danna stayed up until the early hours of the morning Wednesday, buried in New Democrat MP and author Charlie Angus's 2015 book Children of the Broken Treaty, a chronicle of his young First Nations' constituents fight for proper schools and better lives in their Northern Ontario communities.

It was a dreadful but compelling read, an eye-opener for the McGill graduate student who is working on her Master's in epidemiology.

Danna, whose family emigrated from Argentina to the U.S. when she was a child, came to Canada to study nine years ago, firm in her belief it was a fairer, more welcoming place for newcomers.

"Then to find out — Oh, wait! We have huge issues with the way we treat the people who were here to begin with."

Danna was the last person to get back on the shuttle bus to McGill Wednesday evening after venturing to Kahnawake Survival School for Turtle Island Reads, a public event to highlight stories written by and about Indigenous Canadians.

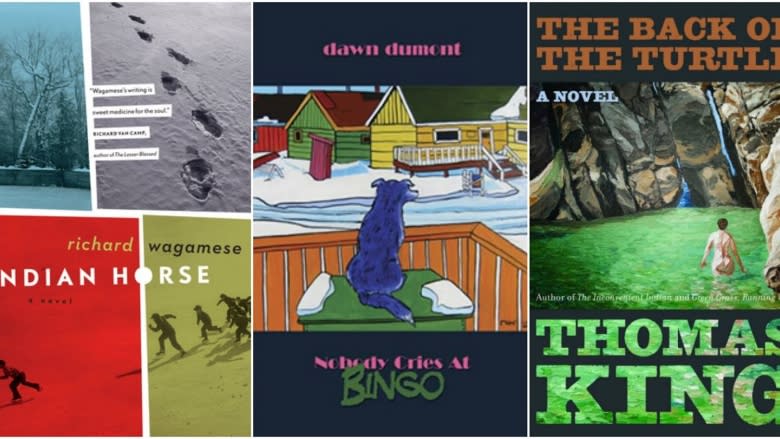

Danna hadn't read any of the three books debated at the inaugural event, but all of them — Richard Wagamese's novel, Indian Horse, Thomas King's The Back of the Turtle and Dawn Dumont's Nobody Cries at Bingo — are now on her list.

- RECAP | Turtle Island Reads audience picks Richard Wagamese's Indian Horse

"I want to read as much as I can get my hands on now," Danna said about her newfound passion.

Connecting to character of Saul Indian Horse

Belle Phillips and her friend Kenya Bero were both students of actor and Kahnawake Survival School teacher Heather White, who championed Indian Horse.

They showed up to cheer on White, who turned them on to Indigenous writers such as Wagamese and Ojibwa playwright and humourist Drew Hayden Taylor.

Taylor's 1993 play Someday was how she learned about the adopting out of Aboriginal children, referred to as the "Sixties Scoop," said Phillips, who is now at John Abbott College studying nursing.

Reading Indian Horse, "I realized a lot more about residential schools and how it affected people's identities," said Bero, a student at Vanier College. "I connected to it. [Saul Indian Horse, the main character] was trying to find himself."

Racism on the ice

Tahothoratie Cross, also a former student of White's, said he could relate to Indian Horse's exploits as a hockey player and his experience of racism in the sport.

"I've played sports all my life, like hockey and lacrosse," said Cross, now studying small business at Champlain College. "Even today, you see racism, and it affects you. You've just got to learn to push it off."

Knowing that other people go through the same thing makes you feel stronger."

A way to learn

Louise Hoelscher is already a passionate fan of Indigenous Canadian literature, and she persuaded two fellow members of her book club to attend Turtle Island Reads — the club's founder, Michelle Tibblin, and Vivia Chow.

"Growing up, I knew nothing about Indigenous people," said Hoelscher. "What I learned about at school were the long dead ones."

But she loves reading, and through that window of books, "I've come to know Native people," she says, "even though I've barely met any."

Tibblin says last June, in honour of Indigenous book month, the club read Thomas King's 2000 coming-of-age novel, Truth and Bright Water.

They're now waiting for the paperback edition of Stolen Sisters, Emmanuelle Walter's powerful work of non-fiction about the 2008 disappearance of Maisy Odjick, 16, and Shannon Alexander, 17, from Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg in West Quebec.

Making amends

Wanda Potrykus, a spoken word poet and editor from Montreal, arrived at Turtle Island Reads with a satchel full of Indigenous literature she's already read and shared widely, including a signed copy of Thomas King's 2003 Massey Lecture series, The Truth about Stories: A Native Narrative.

She is eager to pick up Dumont's Nobody Cries at Bingo: "I love the idea of the title!"

"I'm a one-woman booster of First Nations literature," Potrykus said.

"We have a black mark on us, as non-Native Canadians, about the treatment of Aboriginal people," she said. "The thing that can go partway to make amends is to let people across the world know about them – their history and their stories."

"I figure, we are sharing the land. We should all know each others' stories."

The inaugural Turtle Island Readswas a CBC collaboration with community leaders on the Kahnawake Mohawk territory, the Quebec Writers' Federation and McGill University's Institute for the Public Life of Arts and Ideas.